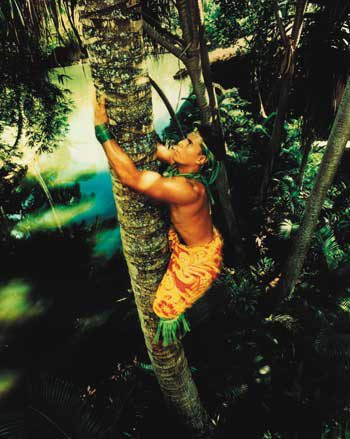

Boyd Lauano, a BYU – Hawaii student from Western Samoa, climbs a coconut tree at the Polynesian Cultural Center.

By Connie Myers

I DON’T JUST hear the drums beating—I feel them echoing in my rib cage, and my pulse seems to keep tempo. Jope Marsilino, a BYU—Hawaii student and my guide, leads me toward the drums along a path shaded by palm trees. The splash of canoe paddles in the lagoon, the hot Hawaiian sun, and the scent of exotic flowers on the ocean breeze all send the same message: We’re in paradise.

We round a hillside and discover a heavily muscled, grass-skirted man pounding on two huge leather and kamani wood drums. Tasseled drumsticks fly high in the air. The drummer pauses and hollers a greeting to the tourists seated around him.

“MALO E LELEI!” Vili Fehoko cries.

“Malo e lelei!” the audience responds, unevenly.

Vili shakes his head in disgust. He tries again. “MALO E LELEI!” he bellows.

“MALO E LELEI!” the crowd replies, more confident now. Satisfied, Vili returns to his drums, beating out rhythms that speak of his Tongan culture, his heritage, his far-off island home.

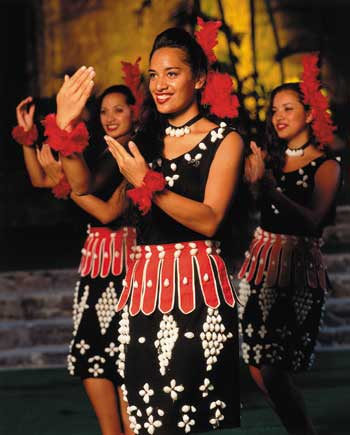

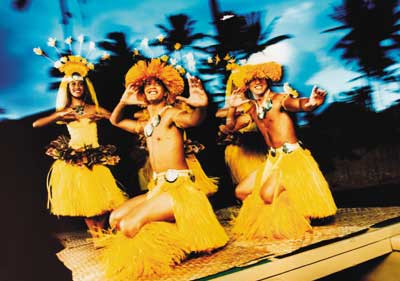

Vili’s drums, the gentle sway of Hawaiian hula, the impossibly swift hips of Tahitian dancers: the Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC) offers them all to tourists from around the world. They come for entertainment and leave with an education after sampling the cultures of Hawaii, Tonga, Fiji, Samoa, Tahiti, the Marquesas, and New Zealand.

But the PCC is not just for tourists. Its true mission is to serve students. At the heart of that mission is the center’s unique work/study program, which supports many students who would otherwise have no access to a college degree.

Today some 700 BYU—Hawaii students work at the Polynesian Cultural Center alongside nearly 300 full-time employees like Vili. The students fill many roles, from groundskeepers to waiters to guides like Jope. Like Jope and Vili, many of them come from Pacific Island nations. They preserve and portray their native cultures while obtaining an education on the neighboring campus.

For these young people the PCC serves as a bridge—to an education, to people of other cultures, and to a strengthened love of their own heritage.

A BRIDGE TO EDUCATION

While Jope Marsilino served an LDS mission in his native Fiji, his mission president encouraged him to apply to BYU—Hawaii. Jope knew it would be difficult if not impossible for him to pay for a college education. But thePCC‘s work/study program made the unlikely possible.

The program, officially titled the International Work Experience Scholarship but often called the sponsored student program, covers all educational expenses, from tuition and books to lodging and meals. In exchange, the student works 19 hours a week at the PCC during the school year and 40 hours a week during the summer. The student receives a small paycheck to cover incidental expenses.

Jope’s first PCC job was at the center’s Fijian village. He felt right at home. “Working in the Fijian village was just like working in Fiji,” he says. Wanting to learn about other cultures as well, he later became a guide, escorting guests from village to village.

Jope is majoring in information systems, a course of study not available to him in Fiji. In an effort to broaden his education, he has added Japanese classes to his school schedule. He wants to become proficient enough to guide Japanese tourists, and he hopes the language experience will benefit him long after he leaves the PCC.

Jope is one of 12,000 BYU—Hawaii students who have earned their educations through the center’s work/study program. During the 2000–2001 academic year, about one-third of BYU—Hawaii’s 2,200 students are working at the PCC; of those, about 450 are sponsored through the program.

The Polynesian Cultural Center was dedicated in 1963 but really got its start when then-LDS Apostle David O. McKay visited the Mormon plantation town of Laie, Hawaii, in 1921. He was inspired as he watched a group of children at a flag ceremony—children of many races from all over the world. He left with a vision of making the town “the center of the education of the people in these islands” (dedication address, Feb. 12, 1955). Thirty-four years later President McKay dedicated the Church College of Hawaii, now Brigham Young University—Hawaii. He also dedicated the town of Laie that it would “become a missionary factor” and influence millions of people.

President McKay’s missionary vision has been fulfilled with the success of the Polynesian Cultural Center, a nonprofit corporation established by the LDS Church. The most popular paid visitor attraction in Hawaii, it draws nearly 1 million visitors each year.

As Vili’s drums pound behind us, Jope leads me to the village of Aotearoa, the Maori name for New Zealand.

We enter the walled compound and are met by a fierce warrior, spear in hand, who shouts at me and places a leaf on the ground at our feet. Jope tells me that if I pick up the leaf, I have come in peace. If I walk on it, I have come to fight. I pick it up. The warrior’s expression softens, and he welcomes us to Aotearoa, the Land of the Long White Cloud.

On one side of the compound, young women in beaded costumes teach children to play ti rakau sticks, tossing and clapping the smooth pairs of sticks in complicated patterns of sound and movement. On the other side guests swing pairs of poi balls on long ropes, laughing as the soft balls collide with heads or hands or other guests. The games look easy when demonstrated by our Maori hostesses but require dexterity, rhythm, and lots of practice. Modern New Zealanders learn these games in grade school, Jope tells me. Ancient Maoris played them to hone hunting skills.

Aotearoa is one of seven re-created villages representing ancient Polynesia. Each is constructed in the traditional way, using authentic methods and materials. In each village native Polynesian students greet visitors, perform traditional songs and dances, and share their love for their culture.

New Zealander Leanna Hamon became part of the Aotearoa village when she arrived at BYU—Hawaii in 1994. Like Jope, Leanna financed her education through the PCC’s work/study program. Her cultural heritage and dancing skills earned her a hostessing spot in Aotearoa, teaching guests about her homeland, more than 4,000 miles away.

But her guests were not the only ones who learned. Leanna had had little previous experience with her Maori heritage, and she learned a lot about Maori language and culture from her coworkers. She later worked at BYU—Hawaii as a tutor, helping students whose first language was not English.

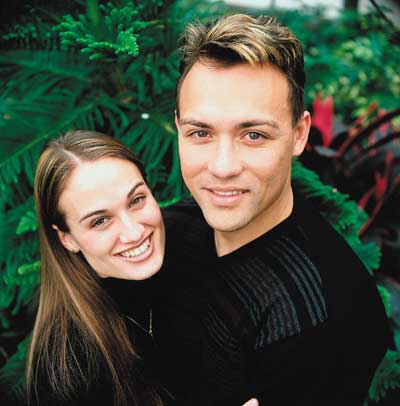

A matchmaking cousin led Leanna to Uale Taotafa, a New Zealander of Samoan and Chinese descent. Uale was also a sponsored student, working as a PCC security guard. They married and, after graduating from BYU—Hawaii together in 1998, they moved to Provo, where Uale works toward a PhD in organic chemistry while Leanna cares for their three children. When Uale graduates, the couple plans to gain work experience in the United States and then make their home in New Zealand.

Leanna credits PCC sponsorship for allowing her and her husband to obtain an education. Without the program Leanna’s education “would have been a real financial burden,” she says. And without a sponsorship “Uale would not have been able to attend BYU—Hawaii at all.”

CULTURAL AMBASSADORS

Sielu Avea, former BYU – Hawaii student and longtime PCC employee, is a champion fire knife dancer. Authentic presentations like his have made the PCC Hawaii’s most popular paid visitor attraction.

From Aotearoa Jope leads me down a winding path to the Samoan village. Here Sielu Avea, champion fire knife dancer and born comedian, entertains us so completely that I don’t realize how much I am learning. Sielu starts a fire with coconut fiber and a rock. He climbs a coconut tree barefoot, with only a loop of cloth to aid him. He strikes improbable poses for pictures with an endless stream of giggling fans.

Sielu came to BYU—Hawaii from Samoa in 1980, Jope tells me, and began working part-time at the PCC. His cultural skills and comedic talents soon earned him a full-time job.

Sielu regularly performs a fire knife dance routine in the PCC‘s night show. His flaming knife burns circles in the air. He tosses it high above the crowd, then catches it. He adds a second knife, hooking the knives together, jumping over them, even doing handsprings.

The fire knife dance is aptly named—Sielu’s hands and arms are covered with burns and scars from his years of performing. His talents have earned the Polynesian Cultural Center an international reputation. In fact, each year the center hosts a fire knife contest that draws challengers from around the world.

Authentic cultural presentations like Sielu’s are one reason political leaders from across the Pacific have honored the PCC for preserving native heritage. Because of the center’s efforts, in 1993 King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV of Tonga conferred on former PCC president Lester W. B. Moore a high chief title—the highest title ever given to a Caucasian foreigner. And in 1997 Moore received the chiefly title of Galumalemana from Western Samoa’s head of state. Government officials from mainland China regularly visit the PCC, hoping to emulate its authenticity in a Chinese cultural center.

I hear the splashes of a waterfall as Jope leads me to the village of the Marquesas. Here a chief’s compound, or tohua, has been built around a central dancing area. Accompanied by the soft beat of drums, we find seats near the Ha’e Manahi’i, the house reserved for guests.

Ancient Marquesan culture emphasized hunting, war, human sacrifice, and cannibalism. Today the Marquesas Islands, like Tahiti, are part of French Polynesia. But as I watch a dance celebrating the hunt for wild pig, see the strong thrusts of the dancers’ spears, and hear the fierce chants of victory, the historic Marquesan culture seems very near.

Later that evening I follow flaming tiki torches to the PCC‘s night show, Horizons! Music sets the mood, from soft Hawaiian hulas to the wild Tahitian drums. Tongan men perform a slap dance, the slapping of their bodies replacing the beating of the drums. The audience cheers as they recognize favorite performers from their daytime journey through the villages, from Vili pounding on oversized drums to Sielu’s show-stopping fire knife dance.

As the show ends, the stage fills with students in costumes from across the Pacific. “Aloha!” they call to the audience. “Aloha!” we respond.

Armed and painted as if for battle, BYU – Hawaii student Shaun Tata, a native of New Zealand, portrays a Maori warrior at the Polynesian Cultural Center. His stance is an example of the wero, a customary Maori challenge to visitors. Since it opened in 1963, the center has helped thousands of BYU – Hawaii students finance their education while preserving their heritage.

When students graduate from BYU—Hawaii and leave the Polynesian Cultural Center, they can make an important impact on their homelands. One such alumnus is Albert Mailo, a Samoan. He started at the PCC in 1964, paddling a canoe in the lagoon and perform- ing in the Samoan village. Though the work/study program had not been established then, “my job offset the costs of my education,” he says.

Mailo says working at the PCC was ideal. “We were able to meet people from all over the world,” he says. “Some of my better memories are from the Polynesian Cultural Center.”

After serving an LDS mission in his homeland, Mailo finished his bachelor’s degree at BYU—Provo in 1972. He went on to earn a law degree from BYU in 1976, then returned home to open his own practice. This formerPCC canoe paddler now serves as American Samoa’s attorney general.

Josefa Sokia of Fiji is another PCC alumnus who has served the LDS Church and his country. Already a successful businessman, Sokia moved his young family to Laie in 1978 so he could complete his education. During his student years, he worked for the PCC‘s Cultural Education Services, demonstrating native crafts and culture to school groups, military tours, and visitors with disabilities.

“Through the center, I and many others like me from the isles of the South Pacific were able to receive a college education at BYU—Hawaii and go out to fulfill its mission—to be the ‘salt of the earth,'” Sokia says. “It is a way of life that I am proud to represent. I am ever grateful to the PCC.”

After completing accounting and business degrees from BYU—Hawaii and doing graduate work in finance at the University of Utah, Sokia returned to Fiji. He now works as a finance manager for the LDS Church in Fiji.

Following their father’s example, two of Sokia’s daughters worked at the PCC while attending BYU—Hawaii. The center’s pattern of education and service is continuing through generations.

Today the students who work at the Polynesian Cultural Center represent 62 countries and six continents. They serve as ambassadors for their cultures and their faith as they share their smiles with tourists. But most of all, they learn—about tourists, about students like themselves from other nations, and about their own capabilities and heritage and faith.