By Lisa Ann Jackson, ‘95

You’ve seen the ads. Reach across your coffee table and grab a magazine and you’ll probably see them again. There’s one for women’s shaving cream. Three young women in short summer dresses dance on a picnic table. All three have their toes turned in and big grins on their faces. Not one is looking at the camera. Flip the page and you’ll see one for a handbag. The model is turned away from the camera, her face is darkened by a shadow, and the purse is draped over her bare back. Turn another page and you’ll see a woman in a swimsuit looking rather contorted. Her legs are in the air, her torso twisted, and her arms stretched over her head. Look closer and you’ll see that she’s wind-surfing and advertising sporting gear.Cheryl Bailey Preston, ’75, a professor at BYU‘s J. Reuben Clark Law School, has scrutinized print advertisements like these for almost a decade. The ads in her huge stack of examples promote everything from perfume to tennis shoes to dish soap. Preston has concluded that many also subtly promote such things as immaturity, submissiveness, and objectification. As a legal scholar she finds these recurring themes disturbing at best.“I have read case after case where issues were raised with respect to women—women attorneys, women witnesses, women litigants—and have tried to determine what assumptions about human behavior were imposed on the actors in terms of deciding who we believed and what we think really happened,” Preston says.

You’ve seen the ads. Reach across your coffee table and grab a magazine and you’ll probably see them again. There’s one for women’s shaving cream. Three young women in short summer dresses dance on a picnic table. All three have their toes turned in and big grins on their faces. Not one is looking at the camera. Flip the page and you’ll see one for a handbag. The model is turned away from the camera, her face is darkened by a shadow, and the purse is draped over her bare back. Turn another page and you’ll see a woman in a swimsuit looking rather contorted. Her legs are in the air, her torso twisted, and her arms stretched over her head. Look closer and you’ll see that she’s wind-surfing and advertising sporting gear.Cheryl Bailey Preston, ’75, a professor at BYU‘s J. Reuben Clark Law School, has scrutinized print advertisements like these for almost a decade. The ads in her huge stack of examples promote everything from perfume to tennis shoes to dish soap. Preston has concluded that many also subtly promote such things as immaturity, submissiveness, and objectification. As a legal scholar she finds these recurring themes disturbing at best.“I have read case after case where issues were raised with respect to women—women attorneys, women witnesses, women litigants—and have tried to determine what assumptions about human behavior were imposed on the actors in terms of deciding who we believed and what we think really happened,” Preston says.

To determine and test these assumptions, she has turned to women’s magazines. “The most effective snapshot of what people do or believe is print advertising,” she says. “Those images are meant to convey some concept to us in a flash, just as we pass the page. Not just the fact of what’s pictured, but they give us a feeling about whether this is desirable, healthy, or fashionable.”

Her conclusion? We’ve come a long way, baby—but in the wrong direction. In the course of her seven years of study, she has observed that the recurring themes play out in two veins: the depiction of women as silly, childish, or unintelligent, and the reduction of women to object status. Combining these observations with independent studies of how women are perceived in various legal settings, Preston is increasingly concerned that subconscious assumptions about women continue to hinder them legally and personally.

To make the legal world and women in general more aware of the effects of such portrayals, Preston has published her findings in several legal journals and given presentations at seminars and conferences, including BYU Women’s Conference. She hopes these efforts and a book to be released next year will help create awareness of—and ultimately change—the effects of such advertising.

Little Girls

A disturbing amount of advertisements are harmful to women, says Preston. She is especially concerned with ads that portray women as objects or as being immature or passive and with what these ads teach society.

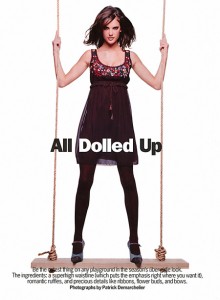

Go back to the ad of the three young women advertising shaving cream. Their toes are turned in, they have playful grins on their faces, and none of them is looking at the camera. These motifs—pigeon toes, quizzical expressions, eyes looking up and away, shrugging shoulders, young models, or women lounging around—each subtly signify that women are confused or immature, can’t think through a problem, or simply have nothing important to do, Preston says.

“Advertisers show these images with such consistency that they normalize them,” says Preston, who has amassed literally thousands of print ads using these motifs. “The more we see them, the more we think they depict normal behavior.”

Which is Preston’s primary concern. She notes that in mock trial studies, jurors are more likely to believe a male witness than they are to believe a female witness, even when they say the same things. A New York task force charged with studying gender in the courts in 1986 and 1987 concluded that women do not receive as much credibility as men from judges, attorneys, and court personnel. She also cites a 1996 survey that revealed that more than 70 percent of respondents observed gender bias against female attorneys from clients, with some respondents reporting that clients assume the female attorney is junior to the male attorney and often defer to the male attorney.

“There are still some assumptions at some unconscious level associated with women in the legal system that are harmful to their success,” Preston says.

She also sees these attitudes anecdotally around her. When reviewing applications for law school, Preston notes that men often write essays that describe their accomplishments and why they will excel in law school. Women, however, often write essays explaining how law school will help them.

“I think there’s something factual about how women in our society are permitted to convey less confidence,” Preston says. “And while humility and openness are good things, at some point women’s lack of confidence conveys to other people that we really aren’t as able. And that’s a self-defeating behavior.”

Faceless Objects

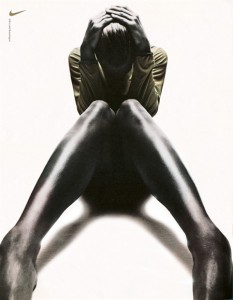

The other vein of recurring themes Preston has observed is the objectification of women. This is accomplished by removing individuating elements such as eyes, focusing on body parts, depicting women as toys or animals, or contorting them in unnatural poses.

Take the ad with the wind surfer. While showing an active woman is to be applauded, according to Preston, the ad undermines itself with the angle and focus of the picture. The perspective is from the water. At that angle the focus is immediately up the woman’s hips and legs, with her torso twisted and her arms flung over her head. Although the brand name is obvious, it takes a second look to determine that she is windsurfing and a third look to determine that she is promoting sporting gear.

In the handbag ad the woman’s back is turned to the camera, and her face is hidden in the shadow, removing all individuating features and making the model a mannequin on which to drape the product.

“We don’t see eyes. We don’t see anything that suggests a real person here. We just see a body like it’s a doll,” says Preston. “Many of the techniques of pornography are used in advertising.”

Preston finds this alarming. Violent crime rates in the United States have dropped in recent years in all categories except violence against women. Preston fears these subtle depictions in print advertising reinforce the problem.

In one high-profile example, convicted rapist and murderer Ted Bundy spoke of his victims as “symbols,” “images,” “the object,” “puppets,” and “dolls.” Preston notes the natural guilt and inhibition that might otherwise stop an offender are eased when the offender thinks he is injuring something less than human—a thing, a toy, or an animal.

Buying In

Preston looks forward to a time when more advertisements, like these, will portray women as capable, mature, and useful individuals. In the meantime she cautions readers to avoid harmful images and, when the cannot, to view such representations with skepticism.

Preston finds the use of these motifs in advertising disturbing, not only because these images may be perpetuated in the minds of potential violent criminals, but also because these images may be selling these concepts to women themselves.

“Women, especially teens and young adults, have a seemingly insatiable taste for fashion magazines filled primarily with glossy advertisements and for the products aggressively marketed by those ads. Do these images affect how women view themselves?” Preston asks.

While it is difficult to document precise cause-and-effect links, Preston immediately dismisses the notion that there is no cause and effect. “If images do not affect behavior, why are American businesses spending nearly $167 billion annually to spread images of their products across every available wall and printed page?”

Because they have done the research, she says. Advertisers are not conspiring against women, asserts Preston. They want to sell products, and they spend billions of dollars to figure out how best to do that. “The overwhelming consistency with which women are depicted in ads tells us that those who spend billions on studying consumer preferences believe America’s primary consumers—women—want it that way,” Preston concludes.

“Many women buy into the way they are portraying us,” says LaNae Valentine, ’81, director of Women’s Services and Resources at BYU. “And we believe we are supposed to be a certain way. Those images are very powerful in influencing our attitudes and beliefs.” Get Smart

Get Smart

While Preston does not advocate adding laws or censoring advertising, she does advocate awareness and education. “When women are aware this message is being sent, they can make choices,” she says.

Preston holds that the most obvious choice is to stop purchasing products that are advertised with these techniques. “One national corporation has, in the question of modesty, horrific advertisements, and yet its store in Provo does well,” she notes incredulously.

She also suggests that people filter out these images as much as possible. “Don’t invite them into your home, not only because of their immodesty but because of the perpetuation of self-defeating behaviors for women,” Preston says.

And because we can’t completely filter images, Preston encourages women and men to heighten their own awareness. “Educate yourself to what the real message is. Look at the women in the ads and say, ‘Does she depict what I want to be or what I think I am?’ Learn to see through those things.”

“I don’t think most of us even notice it until it’s brought to our attention,” says Valentine, who has twice had Preston speak to overflowing crowds. “Women leave saying, ‘I need to pay more attention to advertising and how this is affecting me.'”

Preston believes the pendulum can swing. “Women in America have the power to change advertising,” Preston declares in her book. “When we refuse to purchase goods associated with negative images, advertising will change and society will change.”

Lisa Ann Jackson is a freelance writer living in Mountain View, Calif.