Reflecting the Founders’ spirit of citizenship, BYU faculty respond to the call to serve.

This country relies on citizen leadership at all levels, from the PTA to the presidency. School boards, city councils, state legislatures, and countless associations are populated predominately by part-time volunteers. We are a nation of amateurs. Indeed, professional becomes a term of opprobrium when linked to politician.

I suppose the Founders are partly to blame for this. They left their farms and shops to lead armies, write constitutions, and govern an emergent republic. And then, just as remarkably, they returned to private life. The Founders compose a whole generation of Mr. Smiths who went to Washington, or at least Philadelphia, and then went home—to Mount Vernon, Braintree, Monticello, Montpelier, etc.—to resume their lives as citizens.

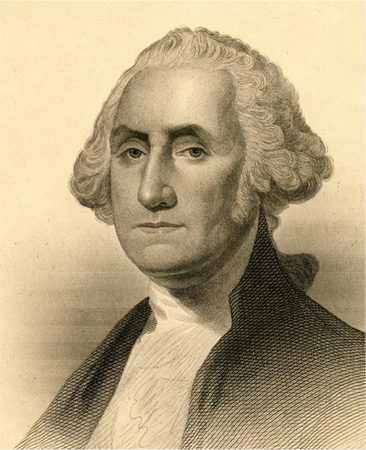

For the founding generation, no one embodied this ideal of citizen leadership more compellingly than George Washington. He was revered as an American Cincinnatus, the ancient Roman general who left his farm to defend his country and then, when offered the dictatorship, refused and returned to his farm. If Washington won the war by the art of strategic retreats, he secured lasting liberty by the art of strategic resignations, first as general of the Continental army and later as president of the United States. His example taught America what it meant to be a public servant in a republic, how citizen leaders should wield power and yield power, and that the duty of office holders is to pursue the public good rather than private gain.

BYU depends on a similar tradition of citizen leadership. We regularly ask faculty to take turns at university governance and then return to teaching and research. In my current assignment, I am privileged to extend invitations to faculty to serve as chairs, directors, deans, and associate vice presidents. For most faculty, such service comes at a price—usually the price of not doing as much of what they love best (teaching and research) to do instead what they love least or not at all (administration). The same is true of those who take on heavy committee assignments. Yet few turn down the invitation to serve. Why?

In part I suppose it is because we are accustomed to accepting callings in the Church, which also depends on lay leadership, but I think it is also because most faculty genuinely love BYU. Few BYU faculty pursue administration as a career track. Rather, they serve out of commitment to being good university citizens. I encourage new chairs and deans to take satisfaction in building a department and college rather than a vita for a time, yet I know full well they will feel moments of regret for students untaught, books and articles unwritten. So I am moved when faculty accept assignments to serve. I am no less touched when they gracefully step down from university service to retire or resume their place in the faculty. Such service in behalf of the common good reflects the spirit of citizenship bequeathed to us by the Founders.

On a recent July 4, my wife and I went on our first hot-air balloon ride. We were the “hare” in the hare and hound balloon competition at Provo’s Freedom Festival. As we glided above BYU, I was struck by the beauty of this place—these 600-plus acres of America I love—and I felt a surge of gratitude for all those, past and present, great and small, who have responded to the call of citizenship to serve both country and college.

We sing of the Founders as those “who more than self their country loved” (“America the Beautiful,” Hymns, 1985, no. 338). We could equally celebrate the generations who have built BYU as those “who more than self their [college] loved.” May we ever keep alive here a spirit of sacrifice and selfless service. For, like America, BYU needs citizens animated by a love that is larger for school than for self.

John Tanner is BYU’s academic vice president. This article is adapted from an essay published online at avp.byu.edu/pages/speeches.html, where you can read more essays by this author.