More Love, Less Contempt

If we are going to beat the problem of contempt, we’re going to need something more radical than civility—something that speaks to our heart’s desire. We need love.

By Arthur C. Brooks in the Winter 2020 Issue

Illustrations by Adam M. Johnson (BA ’07)

Several years ago I came to BYU to deliver a lecture. My wonderful hosts sent me home with a ton of branded souvenirs: T-shirts, mugs—you name it.

One particularly nice gift that I got that day was a briefcase. It had BYU emblazoned across the front. Now, as it happened, I actually needed a new briefcase, but I hesitated to use it because of the logo. It felt a little weird—like false advertising. See, I am not a member of the faculty at BYU, nor am I a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I am a Catholic.

When I expressed this hesitance, my wife, Esther, said, “That’s ridiculous. Use the briefcase. It’s beautiful.”

So I loaded it up and took it out on the road. I travel all the time. I am in airports constantly. And here is the thing. I noticed that people would look at my briefcase and then look up at me. They would have this weird look on their face, like, “I have never seen an aging hipster Mormon before.” That gave me some amusement, but here is the funny part: I found that it was changing my behavior. I was acting with greater love and kindness than I ordinarily would. People would look at my briefcase, and I’d want to help with their luggage. I’d want to give up my place in line. That sort of thing. Why? Because I was unconsciously trying to live up to the high standards of kindness of your church and your university. At the very least, I was trying not to hurt your well-earned reputation.

You know what else? I even stopped carrying cups of coffee. Look, I love coffee, but I didn’t want people to think that a member of your church is a hypocrite! I had this paranoid fantasy of some guy telling his wife, “I saw this Mormon guy in O’Hare Airport ordering a venti latte at Starbucks. I knew they were hypocrites.” I didn’t want that.

And you know what? That briefcase made me a happier person, a more loving person. I was like the person I wanted to be. Why? Because I was trying to be like you. So what is the lesson here? It is not that your BYU briefcases have magical properties. It’s that your greatest witness to the world as members of this community is the conduct of your lives. Our nation and world need this. They need you, more than ever today.

If you pay attention to politics or television or social media, what do you see today? You see recrimination, reproach, insults, and sarcasm. You see leaders at the highest levels of our country who bully and berate those with whom they disagree. You see families torn apart over political disagreements. You see political foes who treat each other as enemies.

People often characterize the current moment in America as being “angry.” If only this were true. Anger is an emotion that occurs when we want to change someone’s behavior and believe that we can do it. According to the research on anger, while anger is often perceived as a negative emotion, it has social purpose. And it is not to drive others away. Rather, it is intended to remove problematic elements of a relationship and bring people back together. Believe it or not, there is no evidence that, in a marriage, anger is correlated with separation or divorce.

For 28 years I have been married to a Spaniard. The secret to the success of my decades of marriage is the lack of correlation between anger and divorce.

The problem is not anger—it is contempt. In the words of the 19th-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, contempt “is the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another.”¹ The destructive power of contempt is well documented in the work of the famous social psychologist and relationship expert John M. Gottman, professor emeritus at the University of Washington in Seattle. Over the course of his work, Gottman has studied thousands of married couples. He has explained that the biggest warning signs for divorce are indicators of contempt. These include sarcasm, sneering, hostile humor, and—worst of all—eye-rolling.²

I have teenage kids. I see lots of eye-rolling. But if you roll your eyes at somebody you love, woe be unto you. That is a little act that effectively says, “You are worthless,” to the one person—your spouse—you should love more than any other. Do you want to see if a couple will end up in divorce court? Watch them discuss contentious topics and see if either partner rolls his or her eyes.

And just as contempt ruins a marriage, it can tear a country apart. America is developing a “culture of contempt”—a habit of seeing people who disagree with us not as merely incorrect or misguided but as worthless.

This is causing incredible harm to our country. One in six Americans has stopped talking to close friends and family members over politics since the 2016 election. Millions are organizing their social lives and curating their news and information to avoid hearing viewpoints differing from their own. Ideological polarization is at higher levels than at any time since the American Civil War.

Listen to the words of Church president Russell M. Nelson: “Hatred among brothers and neighbors has now reduced sacred cities to sites of sorrow.”³ He said this in 2002. Today it is even truer, isn’t it?

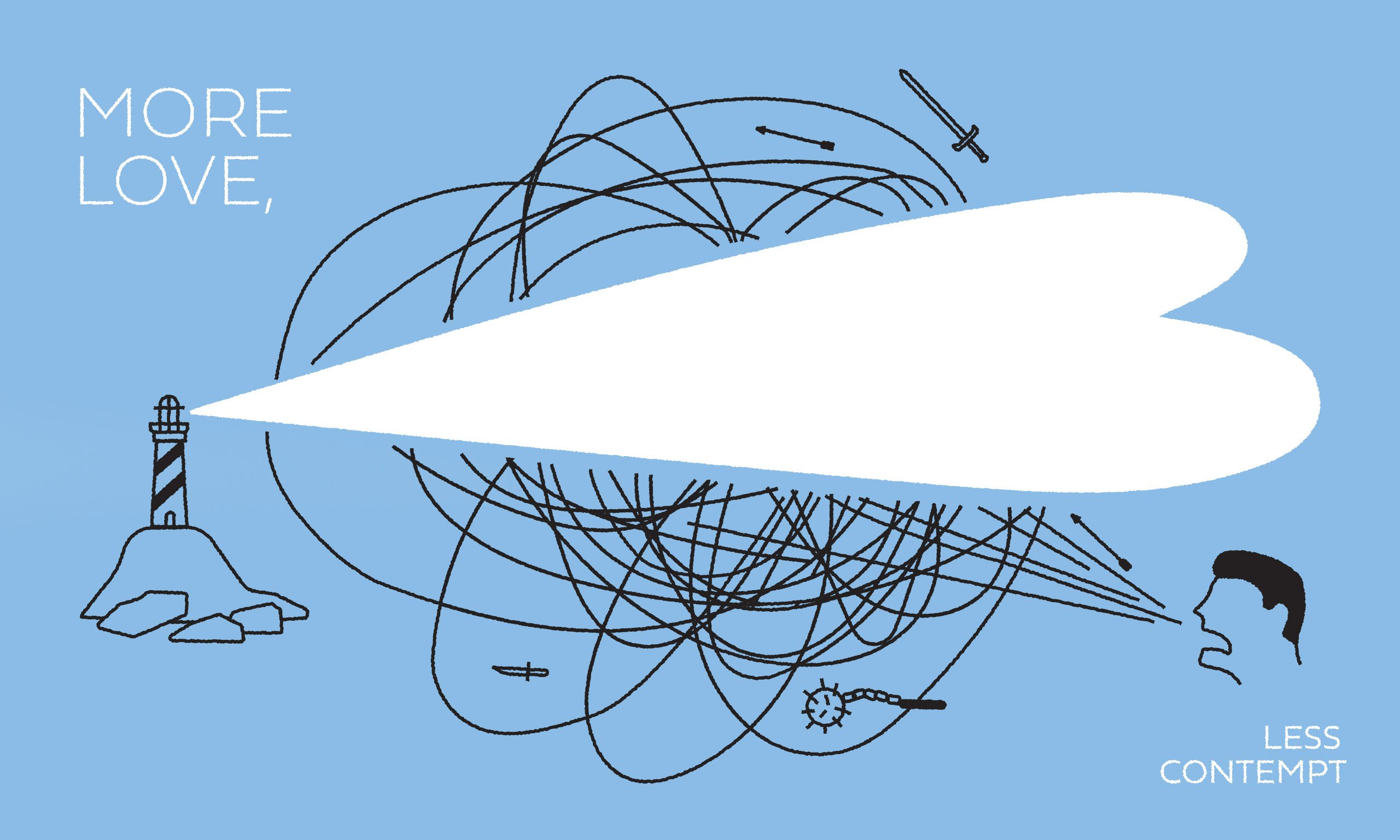

And this is harming more than our nation. Remember that America is a beacon of hope for the rest of the world. We are an example of democratic capitalism that has pulled two billion of our brothers and sisters out of starvation-level poverty over the past half-century alone. This is a nation that has attracted you or your ancestors with the promise of equal opportunity, religious freedom, and a good life for you and your family. When America is torn apart, we become incapable of living up to the plan—the holy plan—for our nation, which is to shine a light for the rest of the world.

“Your greatest witness . . . is the conduct of your lives.”

So what do we need? Some say we need to agree more, but that is wrong. Disagreement is good, because competition is good. It makes us sharp and strong, whether in sports, in politics, in economics, or in the world of ideas. We don’t need to disagree less; we need to disagree better. Other people say we need more civility. But that is wrong too, because civility is a hopelessly low standard for us as Americans. Imagine that I told you that my wife, Esther, and I are “civil to each other.” You would say we need to get some counseling.

If we are going to beat the problem of contempt, we are going to need something more radical than civility—something that speaks to our heart’s true desire. We need love, which was defined by Saint Thomas Aquinas as “to will the good of another.”⁴ We need a new generation ready to model lives of love in the midst of a culture of contempt. We need young people who can live out in today’s culture the words of Helaman:

And it came to pass that they did go forth, and did minister unto the people. . . .

And as many as were convinced did lay down their weapons of war, and also their hatred and the tradition of their fathers. [Hel. 5:50–51]

He was talking about you.

Make no mistake, this isn’t easy to do. It requires people who will not run away from the problem, who are unafraid to infiltrate the culture of contempt, and who are capable of modeling a better set of values. This requires the agility to be in the culture but not of it. When you think of it, it’s kind of like missionary work, isn’t it? Missionaries have the training and experience to participate in society without getting sucked into its pathologies. They have the courage and fortitude necessary to face resistance and go forth with the joy that comes from sharing the truth.

“We need a new generation ready to model lives of love in the midst of a culture of contempt.”

Near my home there is a Catholic retreat center where my wife and I teach marriage-preparation classes for engaged couples. In the chapel there is a sign posted over the door—not the door coming in but rather the door going out into the parking lot. It is written for people to look at as they are leaving. The sign says, “You are now entering mission territory.” The message is simple, but it is really profound: You are here because you have found what is good and true, but you are going to go out where people have not yet found what you have discovered. You have the privilege of sharing it—with joy and with confidence.

That should be a message to you who want to make America and the world better. You know what our world needs: more love, less contempt. You have the skills and training to make this a reality. Most of you have been raised your whole lives with the values that I magically got for a few minutes from my BYU briefcase. You have received an education through hard work at one of the world’s greatest universities. You have prepared your whole lives to enter the world and make it better. This university has an unofficial motto: “Enter to learn; go forth to serve.” You get to live up to that motto, starting today—to sanctify your learning and ordinary work by lifting up and bringing together our great nation.

You are now reentering mission territory.

Arthur C. Brooks—best-selling author, social scientist, and president of the American Enterprise Institute—delivered this BYU commencement address on April 25, 2019, when he received an honorary doctorate. Find the full text of this and more than 2,000 other talks in video, audio, and print formats at speeches.byu.edu.

Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

NOTES

- Arthur Schopenhauer, “On Psychology,” Essays and Aphorisms, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (London: Penguin Books, 2004), p. 170.

- See John M. Gottman and Nan Silver, The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work: A Practical Guide from the Country’s Foremost Relationship Expert (New York: Harmony Books, 2015), p. 34.

- Russell M. Nelson, “Blessed Are the Peacemakers,” Ensign, November 2002.

- See Saint Thomas Aquinas, answer to Question 59, Article 4, “Whether Whoever Does an Injustice Sins Mortally?” in the Second Part of the Second Part, Summa Theologica (1273).