BYU scholars illuminate dark corners of politics and help change the system.

Through BYU’s Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy, (from left) Quin Monson, David Magleby, and Kelly Patterson track the millions of soft-money dollars donated to shift public opinion and tilt tight races. Photo by Bradley Slade.

When charts he had created were shown on the Senate floor, it struck BYU professor David B. Magleby that the data he had been gathering would not only inform congressional debate about campaign finance reform, but it would also likely end up in any U.S. Supreme Court challenge of the resulting legislation.

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), including the Snowe-Jeffords amendment—a direct result of Magleby’s research—was signed into law in March 2002. It was immediately challenged in court, and Magleby’s prediction came true: he was invited to write a report for the district court case, and the “Magleby Report,” was cited three times in the split Supreme Court decision handed down at the end of 2003.

“When you get to the courts, you need solid evidence, and that’s what David provided,” says Arthur Lupia, a University of Michigan political science professor who studies elections and democracy.

The purpose of BCRA was to break the connection between office holders and large contributors and otherwise rein in out-of-control soft-money contributions and spending that had become rampant since the 1996 elections. Under previous campaign finance law, soft money, which consists of essentially unlimited and undisclosed contributions from individuals, interest groups, and corporations, could not legally be used for electing federal candidates. Due to loopholes in the law, however, campaign managers began skirting the restrictions.

Since the 1998 elections, the focus of Magleby and company’s research, underwritten by grants from the Pew Charitable Trusts, has been to track the notoriously elusive soft money. They use a reconnaissance network of academics, local voters, and BYU alumni to gather nonpartisan, objective data on the impact of soft money on the election process.

Their work has already played a role in the national debate, and Magleby’s team is now gathering its fourth election year of data, the first year in which BCRA governs campaign finance.

The Advent of Soft Money

Under the 1971 Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) and subsequent Federal Elections Commission (FEC) advisory opinions, candidates and parties could raise and spend hard money—fully disclosed, limited contributions to federal campaigns—for the express purpose of getting a candidate elected. Parties could raise and spend soft money for the generic purpose of “party building.”

For a quarter of a century, campaigns generally abided by the same interpretation of the FECA rules. The Christian Coalition cracked open the soft-money door when it sent out printed voter guides in 1992 and 1994 to no FEC objections.

Then in 1996 Bill Clinton’s chief political strategist, Dick Morris, tuned in to some technicalities in the law and suggested the strategy of having the Democratic Party spend its coffers of soft money to promote the president and his agenda.

The key was to avoid the “magic words” found in a footnote from a 1976 Supreme Court ruling on FECA, where electioneering was defined with specific words such as elect, defeat, vote for, or vote against. As long as parties or interest groups avoided such direct commands, they could run ads encouraging voters to, for instance, “Call Senator John Doe and tell him to stop polluting the environment” or “Show Representative Jane Doe you favor economic growth.”

“It wasn’t okay until then. The parties assumed they couldn’t do that,” notes Magleby, a political science professor and dean of BYU’s College of Family, Home, and Social Sciences. “It was not until they did it and got away with it that the Dole/Kemp campaign did the same thing, and then we had the world of soft money as we’ve come to know it.”

They got away with it because the FEC declined to intervene, allowing national parties to spend their soft-money wells to help representatives, senators, and presidents win tight races.

Also governed by electioneering guidelines and the “magic words” definition, interest groups were technically banned from becoming involved in direct electioneering activities with their general funds. But they pushed the limits.

The American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations followed the Christian Coalition’s lead and spent $35 million on issue ads and get-out-the-vote activities.

“Organized labor said, ‘We can run ads attacking a candidate and never use [the magic] words; and if we never use those words, we cannot only do whatever we want, we never have to disclose what we do.’ And so they did that in 1996,” Magleby says. “Again, the FEC didn’t do anything about it.”

Finding and Following Soft Money

Upon seeing these two major shifts, Magleby decided to study these trends in 1998. Outside money—a shorthand expression Magleby uses to include soft money and other monies outside a specific candidate’s campaign—is extremely difficult to track and quantify because there has been no reporting requirements on these contributions.

“To study this, you had to get creative because nobody had a data set they could send you by UPS Second Day,” Magleby says. “We had to go out and get the data ourselves.”

To do this, Magleby identified the most competitive races—because outside money is spent only on the most contested seats—and recruited academics to do case studies of their local federal elections. Each academic was responsible for gathering as much ad-buy data as local radio and television stations were willing to give and for enlisting a network of local voters who, along with a control group primarily made up of BYU alumni, were to collect, log, and submit all campaign communications they received.

Finally, the researchers conducted surveys and focus groups to figure out the impact on voters of election activities funded by outside money.

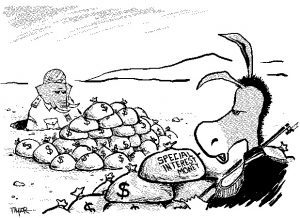

Cartoon by Aaron Taylor

Years of research have yielded all kinds of interesting data to Magleby and his team. Past findings revealed that money spent by political parties and interest groups in competitive races often equals or exceeds the total spending by the candidates themselves, effectively doubling the spending in these close contests.

The researchers have also shown that under pre-BCRA disclosure laws, voters had a hard time distinguishing between advertisements from candidates and those by interest groups and political parties.

Additionally, Magleby has tested the magic words through surveys and focus groups and definitively concluded that an ad could avoid all of the magic words and still communicate an electioneering message.

Making Reforms

Politicians became acutely aware of campaign finance issues with the breakaway soft-money spending introduced in the 1996 elections. By 1999, reform legislation, including the McCain-Feingold and Shays-Meehan bills, was being hotly debated in the House and Senate.

“Did that money come with strings attached? Did it have the potential to corrupt the politicians?” asks Magleby. “The answer to Congress and eventually the Supreme Court was yes, especially when it was in such large amounts.”

Early in the debate, Senators Olympia Snowe (R-Maine) and James Jeffords (I-Vermont) learned of Magleby’s soft-money research and invited him to Washington, D.C., to brief their staffs on his findings. In response to his research, the senators wrote the Snowe-Jeffords amendment, crafting a definition of electioneering based on Magleby’s studies that the magic words were not adequate.

Cartoon by Aaron Taylor

Even while the debates raged in the House and Senate, the national parties raised record amounts of soft money during 2000 and 2002. With the passage of the BCRA in March 2002, the debate shifted to the legal arena, where the Supreme Court upheld the act more than a year and a half later, with both the majority and minority opinions of the divided court citing Magleby’s findings.

Included in BCRA’s provisions are the following rules: national political parties can no longer accept soft money contributions. Additionally, corporations and labor unions are prohibited from making or funding electioneering communications, which are now defined as broadcast communications referring to a clearly identifiable candidate and which are distributed to voters within 60 days of a general election and within 30 days of a primary.

Life After BCRA

The Supreme Court’s decision did little to stem Magleby’s scrutiny of campaign financing. With the 2004 election year underway, Magleby is working with Kelly D. Patterson, ’82, BYUPolitical Science Department chair and director of BYU’s Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy, and J. Quin Monson, ’96, assistant director of the center and an assistant professor of political science, to study the first election under the new rules and see where the soft money will go. Magleby anticipates that Congress and the courts will revisit campaign finance in the next five years and hopes the 2004 research will help inform that process.

BCRA bans soft money for parties, but the people who give the money are not banned,” Magleby notes. “They could find some other way to try to spend the money.”

It’s what Justices John Paul Stevens and Sandra Day O’Connor predicted in their majority opinion. “Money, like water, will always find an outlet,” they wrote. The purpose of this year’s research is to follow that flow.

This election year has already seen the development of groups called 527s (named for the section of the tax code that governs them). Early in the cycle these Democrat-leaning 527s, such as Moveon.org and Americans Coming Together, focused their efforts squarely in battleground states, expressly seeking to defeat Republicans through voter-mobilization efforts, issue advocacy, and personal contact.

President Bush pressed the FEC to clamp down on these groups, but in May the FEC decided not to rein them in before the 2004 elections. Republican-leaning 527s have since sprung up in response.

And although there remains the question of where soft money will go and how it will be spent throughout the current election, that is precisely what these researchers are working to find out.

“Call this investigative scholarship,” said Brooks Jackson, political journalist, in response to Magleby’s findings after his first year of research in 1998. “Professor Magleby’s research shines a light into the dark corners of American politics, revealing ways that interest groups spend millions to influence elections.”

Lisa Ann Jackson is an Internet content specialist for the Church of Jesus Christ.