Good Enough

In language and in life, what makes something—or someone—good?

By Joey C. Franklin (BA ’07) in the Summer 2021 Issue

Illustrations by Adam M. Johnson (BA ’07)

A few years ago, I stepped out of my office and bumped into a custodian walking down the hall. For the longest time, he and I had been strangers working in the same building, but one morning we shared an elevator ride and some small talk, and now, when our paths cross like this, we exchange pleasantries in the clunky manner of coworkers who might, given time, become friends.

“How are you?” I asked, and he said he was good, but then he corrected himself.

“Eh, I mean I’m well,” he said and laughed.

I’ve thought a lot about this brief moment of grammatical self-consciousness. When you teach writing for a living, everyone assumes you’re a grammar Nazi, that you’ll think less of them for their ain’ts and gonnas, their anxious use of anxious, their misplaced lays and loose-lipped lies. But if they only knew the truth—that I still can’t explain why you’re not supposed to end a sentence with a preposition, that I always have to look up the difference between lay and lie, and that I’d be hard pressed to explain why “I’m well” is better than “I’m good”—they might not second-guess their language so often around me; my custodian friend might not walk down the halls of the English Department wearing his language like a millstone.

Another time I attended a conference hosted by a small, energetic woman who did a lot of gesticulating with a clipboard and thanking people by saying, “Well, aren’t you sweet?”

During a break between panel sessions, I asked her where she was from, and when she said Georgia, I was surprised because she didn’t have much of a Southern accent.

“I learned to tone it down in college,” she said. “But it was worth it.”

“What was it worth?” I asked.

“About 10 IQ points.”

We laughed, but at the time I lived in Lubbock, Texas, and I knew exactly what she was talking about—the accents in that part of the country are impressive. From the deepest drawls to the slightest twangs, vowels uttered on the Llano Estacado swing loose and relaxed—like saddle bags over the rump of a lazy horse, like a Colt .45 slack-holstered at the hip, like a tight-rolled cigar balanced on the lips. At least that’s how I heard them—with the condescending ear of a boy who had watched too many Hollywood Westerns. More than once, I found myself thinking, “Everyone sounds like a bunch of hicks.”

Getting to know people usually helped readjust my assumptions, but when it came to first impressions, the lower the swing in a person’s West Texas drawl, the harder those assumptions were to shake. Linguists call this accent bias, though that is too nice a phrase for the plainspoken bigotry of the thing. It’s one bitter fruit of that often-misguided question of right and wrong language and a consequence of who gets to decide what’s good and what’s not.

Up to No Good

When it comes to judgmental inclinations, accent bias is perhaps the least of my worries. From the moment I wake up, I’m passing judgment on my kids for not putting away their shoes; on my wife, Melissa, for not making her side of the bed; on the dog for being unable to think about anything but fetch. Step outside, and I’m judging that neighbor with a yard full of weeds—and also that neighbor with the perfect Kentucky bluegrass. And what about the food stains on the face of that kid who comes over to play? Don’t his parents notice? Or the preschooler at church with perfectly gelled hair and a three-piece suit? That’s borderline abuse.

“Walk with me on my freshly mowed lawn, and notice the lines cut more or less on the diagonal. . . . Aren’t I good?”

These are all actual thoughts I’ve briefly entertained, and as fleeting as these unsavory judgments are, they recur, I think, because, like most of us, I’m looking for some concrete indication that my own life isn’t a complete mess. This kind of selective comparison makes it easy to think I’m doing alright (or is it all right?). Unfortunately, such comparisons also reduce goodness to a checklist of social expectations, driven more often by nostalgia, insecurity, and ego than by any internal moral compass.

And the problem is, I love checklists. I want goodness to be simple. Give me a set of requirements to complete, a badge to earn. Please, gold stars, somebody. Check me out as I send my boys off to school with washed faces; walk with me on my freshly mowed lawn, and notice the lines cut more or less on the diagonal; and ask my wife, she’ll tell you: I always make my side of the bed, and usually hers too. Aren’t I good? Or do I mean well?

The Good Old Days

Prescriptive notions of grammar have been helping us determine the difference between good and bad language for so long that it’s hard to imagine a time when all those rules were ever up for discussion. And yet, if you and I could go back a few hundred years, we’d find a raucous dispute about the vulgar, unruly nature of the English tongue. Commentators wondered whether mongrel English could really have a grammar at all. Greek? Sure. Latin? Certissime! Those ancient and noble languages seemed, to scholars of the European Enlightenment, the very linguistic embodiment of reason and natural order. But English?

Nevertheless, hundreds of authors gave it a go. The first of these grammar books were used to make Latin lessons easier, and in the process scholars fabricated all manner of artificial relationships between the two languages—a move that gave birth to many groundless prohibitions in English. No double negative? No split infinitive? No prepositions at the end of a sentence? You can blame all that on Latin.

Soon though, scholars were studying English for its own sake, and everyone with a quill had an opinion on how one should speak and write. Today, when Smithsonian magazine claims that “Most of What You Think You Know About Grammar Is Wrong” or Huffington Post runs an article on “Why Only Some Grammar Rules Are Breakable,” they’re perpetuating arguments that got started hundreds of years ago. But more than that, they’re reminding us of the relationship between language and social propriety, that the words we use have a weight we can only partially know, and that, in many situations, goodness is relative.

No Good Deed Goes Unpunished

In my home growing up, I was the good kid, but the bar was pretty low. My older siblings had made careers out of suburban juvenile delinquency, skipping class, blowing off homework, and sneaking out for late-night rendezvous with friends. To compensate, I went to church most every Sunday, stayed on the honor roll at school, and dated a series of respectable young women. I still remember the tone of surprise from a high school guidance counselor as she looked over my academic record during a college-prep interview: “You’re a Franklin?”

But I was still a teenager, and something about being “good” left a sour taste in my mouth—like I might be missing out on some important aspect of juvenile self-actualization. And so I occasionally tried on a little rebellion like a boy who tries on his older brother’s smoky leather jacket—I humored that need to see a different version of myself in the mirror. What would I look like as an underachiever? As a kid who did whatever he wanted to? To test these questions, I skipped a bit of class, left a few assignments unfinished, and even snuck out once in the middle of the night (though I didn’t make it far—a passing cop just happened to see me come out of my garage and told me to go back home). And while these pedestrian risks helped appease a fear that I might be missing out on something, test-driving that devil-may-care attitude had the unintended consequence of making me feel, most of the time, like a complete hypocrite.

I’m 40 now, which means I should have all kinds of insight and maturity about true goodness. But, as it is, the universe has blessed me with children, so instead I spend most of my time reliving my own childhood mistakes and worrying about whether or not history will repeat itself.

My three boys have all committed the various misdemeanors of childhood—fighting in the basement, pestering each other to tears, claiming they’ve brushed their teeth when clearly they have not. And occasionally they’ve been guilty of worse: lying about where they’re going, stealing money from each other, or picking on some kid at school. On particularly trying days I can be overwhelmed by that unique version of irrational anxiety that only parents can fully appreciate—it’s a snowballing apprehension that cuts a quick path from “You cheated on your homework?” to “You’ll end up a 40-year-old alcoholic living in our basement.” In the face of that anxiety, I am impatient for them to develop their own ethical backbones.

And impatience is really what it comes down to. If parenting has taught me anything, it’s that kids eventually figure things out. They learn to sleep through the night, to eat without a bib, to say thank you, and to keep their hands off their brothers’ piggy banks. But no matter what benchmarks they reach, I’m impatient for the next one. “Hurry,” I want to say. “You’ve got to grow up.” Never mind that in my own stumbling process of growing up, time has been, by far, the most important ingredient.

If we let it, time will teach us how to groom and care for ourselves, but it will also burden us with maladies both physical and mental, with cancers and broken bones and broken hearts, with depression and loneliness and sorrows and fears—and all these will make us targets for the kindness of others. Time will also provide us a friend, a partner, a parent, or, say, three impressionable sons to care for—human relationships as the ultimate incubators for our own burgeoning morality.

Paved with Good Intentions

In some ways religion offers me and my boys a ready-made grammar of goodness, a dogma of dos and don’ts to keep us in line. And I read the Proverbs of Solomon with fear and trembling: “Train up a child in the way he should go: and when he is old, he will not depart from it” (22:6). But if training up a child were as simple as sending him off to church, we’d have fewer God-fearing men in prison right now. I think Solomon’s counsel has as much to do with what my boys learn from me as with anything they might learn at Sunday School.

I’m fond of the Good Samaritan approach: pull over and help stalled motorists; bake bread for the neighbors; shovel snow for the old couple next door. But my motives have always felt muddy. Is it good enough to do good because I hope my boys will learn from it? I’m pretty sure true goodness means that your left hand really doesn’t know, or at least doesn’t care to point out, what your right hand is doing. And yet, every time my left hand doeth so much as pick up some litter, my right hand wants to shoot up into the air and say, “Hey, boys, over here. No big deal. Just saving the world, one piece of trash at a time.”

“Stopping on the road to Jericho was not what made the Samaritan good; it was his goodness that made him stop.”

“Pure religion,” writes James, “is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world” (James 1:27). It’s that last part that seems so hard: that boundless, organic goodness with no worldly entanglements; a willingness to do the right thing not because we hope to be seen of other people but because we’ve learned to truly see all people as they really are.

Here’s a truth I’m still trying to grasp: stopping on the road to Jericho was not what made the Samaritan good; it was his goodness that made him stop.

One Good Deed Deserves Another

Back when we lived in Lubbock, I served as an elders quorum president and got to know a man named Joe who’d lived most of his life on the street. By pretty much anyone’s standard, Joe’s life had been rough. He’d flunked out of school, gotten expelled from the army, and built a criminal record that made finding work next to impossible. On top of that, he sported a large neck tattoo and occasionally started sentences with the phrase, “I’m not racist, but . . .” If we’d crossed paths on the bus or in a dark alley in the city instead of at church, I probably would have avoided him.

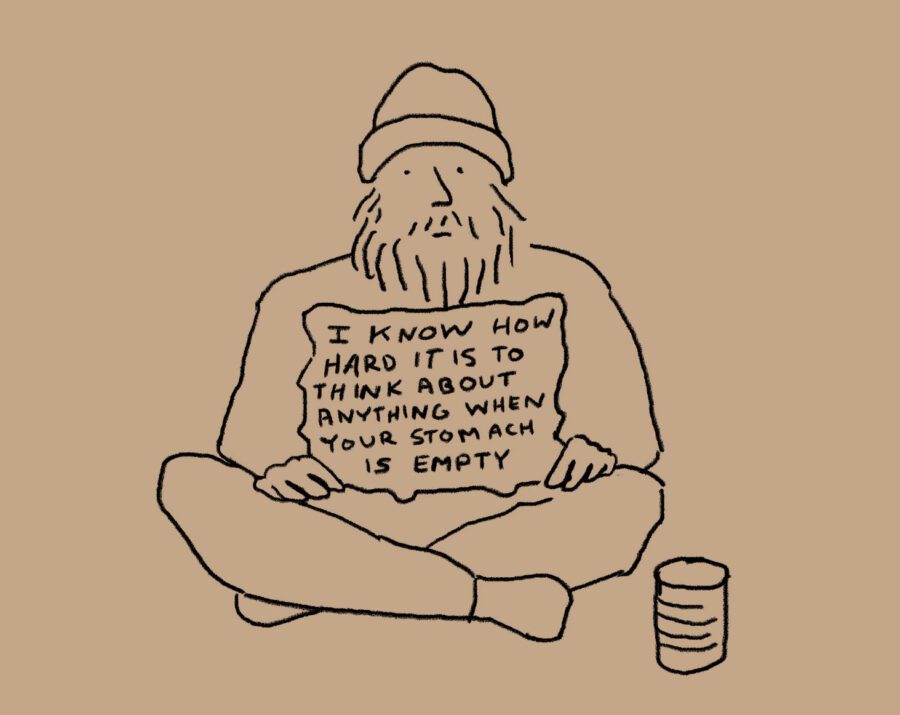

As it was, I spent several months giving Joe rides to doctors’ appointments, the grocery store, and the employment office. And as happens when you spend real time getting to know someone that you might otherwise prejudge, Joe and I became friends. He told me stories about street life and his time in prison, but he also told me about the countryside of his childhood and how much he liked working on cars. I watched him take in stray animals and offer his couch to homeless friends. And, even though he often resorted to panhandling so he could eat, I also saw him give away food and cash with abandon.

Joe’s generosity perplexed me. There were strict rules he needed to follow to become independent, but when we talked about the importance of careful spending and I suggested he should give less away, he shrugged. “I’ve lived on those streets,” he told me. “I know how hard it is to think about anything when your stomach is empty.” Joe and I were operating according to different realms of possibility when it came to goodness. Mine was wrapped up in the belief that if we learn to speak and act a certain way, the system will eventually work for us. His, on the other hand, seemed based on the premise that it’s always better to feed someone today and then worry about the system tomorrow.

It’s All Good

Turns out, the I’m-good-versus-I’m-well debate is as arbitrary as any English language prescription out there. Consider this: in English, adjectives (like good) modify nouns (“I am a good person”), and adverbs (like well) modify verbs (“I speak English well”). So, if am is a verb, then good is no good, because good is an adjective, and using an adjective to modify a verb is no bueno.

However, am belongs to a fraternity of 60 or so verbs called linking verbs—like feels, looks, and seems. Unlike other verbs, which are busy describing activities, these have only one job: linking subjects to predicates. Thus: I (subject) am good (predicate). In fact, most grammarians worth their weight in dictionaries say we should probably reserve “I am well” for conversations about our health, which means that when my custodian friend flinched at his supposedly improper use of “I am good,” he was not only good, he was just fine.

Which has me thinking that perhaps the cure for overly cautious prescriptions about grammar is to remember that language is about communication, self-expression, and, perhaps most pointedly, about art. Every language is built on fundamental principles, but these are merely foundations. The sage writers of our literary past are memorable precisely because they found new ways to make old language teach us something vital about our own humanity.

“[My kids] are further along than I often give them credit for.”

And as in language and literature, so in life. Yes, I want my sons to mind the counsel they court in Sunday School and in the poetry of holy texts and in the words of wise adults (including, sometimes, me), but for all my anxiety about them and the choices they have to make along the road to becoming independent, would I really be happy if they merely did what I wanted them to? Certainly, I want them to be good, but I want them to be good because they are in love with the mysterious, contradictory, peculiar beauty of goodness, not because they’re resigned to doing what they’re told.

And if I allow myself to see them more honestly, then really they’re further along than I often give them credit for. My youngest son may be a pathological liar when it comes to whether or not he’s brushed his teeth, but he’s quick with hugs and apologies, and he delights in pancake breakfasts and Play-Doh. The one in the middle sometimes sulks like Eeyore and has an allergy to speaking up for himself, but he also has an uncanny instinct for the emotional needs of younger children. Whenever his little cousin comes over, my son is right there on the floor with him playing games or helping him climb into a laundry basket so he can scoot him around the house. And my oldest—while he is occasionally the perfect picture of a distant teenage boy—he often surprises me with his good nature and willingness to work, dropping everything to help me run an errand or deliver something to a neighbor. Recently I caught him washing dishes late at night, and when I offered to help, he simply smiled and said, “I got this.”

In such moments, part of me wants some credit, but that’s only fair if I also take the blame for their less stellar moments. And the reality is, such transference is a fact of life. Melissa, me, our boys—we are bound to one another, as most families are, not merely by blood, but by habit, and by the inevitable education that comes with spending so much of our lives together. We are all on the same path, and they’re simply figuring out for themselves what we must all figure out—that for whatever religious, moral, or ethical prescriptions we were or were not taught as children, the art of true goodness is a type of human divinity, and we must evolve toward it.

Joey Franklin is a BYU creative writing professor. This article is excerpted from an essay in his book Delusions of Grandeur: American Essays, published in 2020.

Feedback: Send comments on this story to magazine@byu.edu.