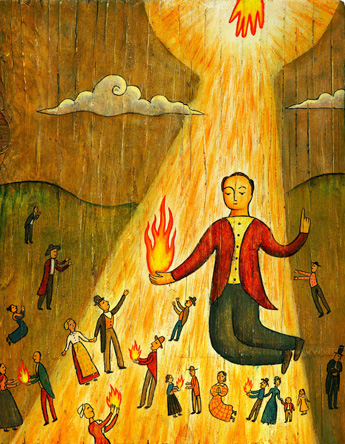

Fire from Heaven: The First Vision and Its Aftermath

A legendary professor’s classic talk and six artistic takes by artists with BYU connections tell the story of the First Vision.

By Truman G. Madsen in the Spring 2020 Issue

In 1969 BYU Studies published a collection of the four known written accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision. One was first recorded in 1832; another in 1835, after a visit Joseph had with a Jewish visitor named Matthias; there is the 1838 statement, which has been published to the world in the Pearl of Great Price; and finally, the well-known Wentworth letter, written in 1842 to the Chicago Democrat, in which the Prophet briefly recapitulated his First Vision.

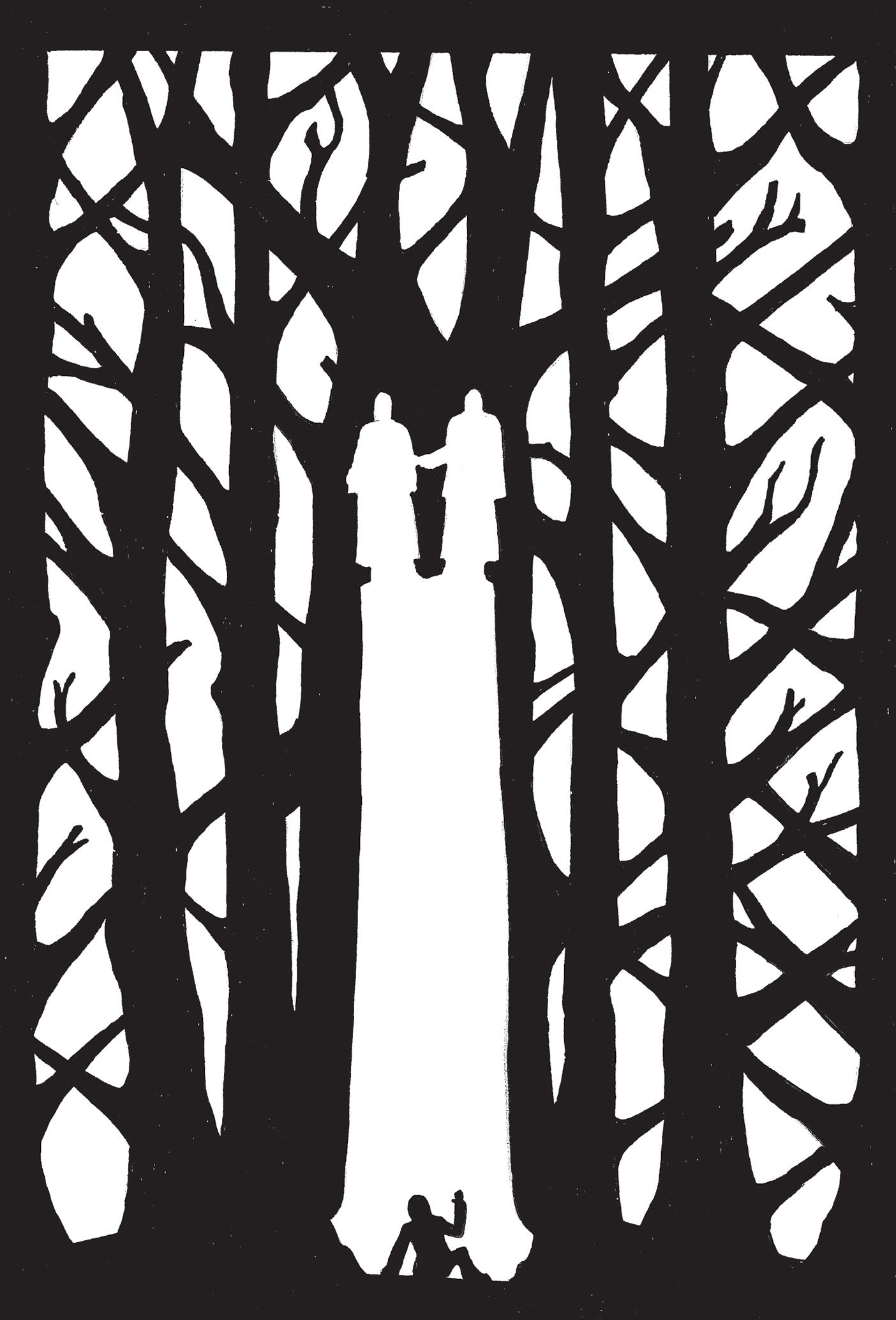

In the earliest account, Joseph speaks of his days in Vermont. There and later in New York Joseph would look up at night and marvel at the symmetry and the beauty and the order of the heavens. Something in him said, “Behind that there must be a majestic creator of the heavens.” The contrast between his boyhood awareness and the confusion he saw on this planet was not just difficult; it seared his soul. The divisions he laments in Palmyra were not just among and between others, neighbors and friends; they were in his own family. He had at least one relative in every church in Palmyra, so that his family was utterly spread. Order in heaven, disorder on earth. How could God be responsible for both?

The record makes it clear that before the sacred experience in the grove it had never occurred to Joseph that all the influential churches were in error. The question he put to Jesus Christ when he recovered himself was not, “Is there a true church in the world?” The question was, “Which church is true?” He assumed that at least one had to be true. The answer therefore was all the more striking and startling: “Join none of them.”

The Reverend George Lane may have been the man who first recommended in Joseph Smith’s hearing, “Let him ask of God.” That specific passage in James 1:5 was mentioned in some of the minister’s sermons. A Methodist, he was associated with revivals in western New York. Joseph later talks of a Methodist preacher he was with soon after the vision, a person who was, he says, “active in the before mentioned religious excitement.” Imagine (and this to me is poignant) Joseph at age 14—full as he was of the glory, the remarkable experience, and the excitement of it—recounting his experience to this man. And the man’s response was, “Oh no, that could not be of God. Those things don’t happen anymore.”

So one lacking wisdom ought to go and pray about it. By all means let him ask of God. But to this man the answer seemed . . . well, too much. Heaven had come too close. We can almost visualize the boy—pure-minded, spontaneous, even a little unrestrained, as teenagers are—being struck by the wonder of this marvelous answer to prayer. “Wow! It worked! You told me to do it. I did it.” And the response was, “Shucks, boy, it’s all of the devil.” The boy’s smile slowly disappeared. And he learned early that to testify of divine manifestations was to stir up darkness and to call down wrath. That wrath finally evolved into bullets.

A Dark Influence

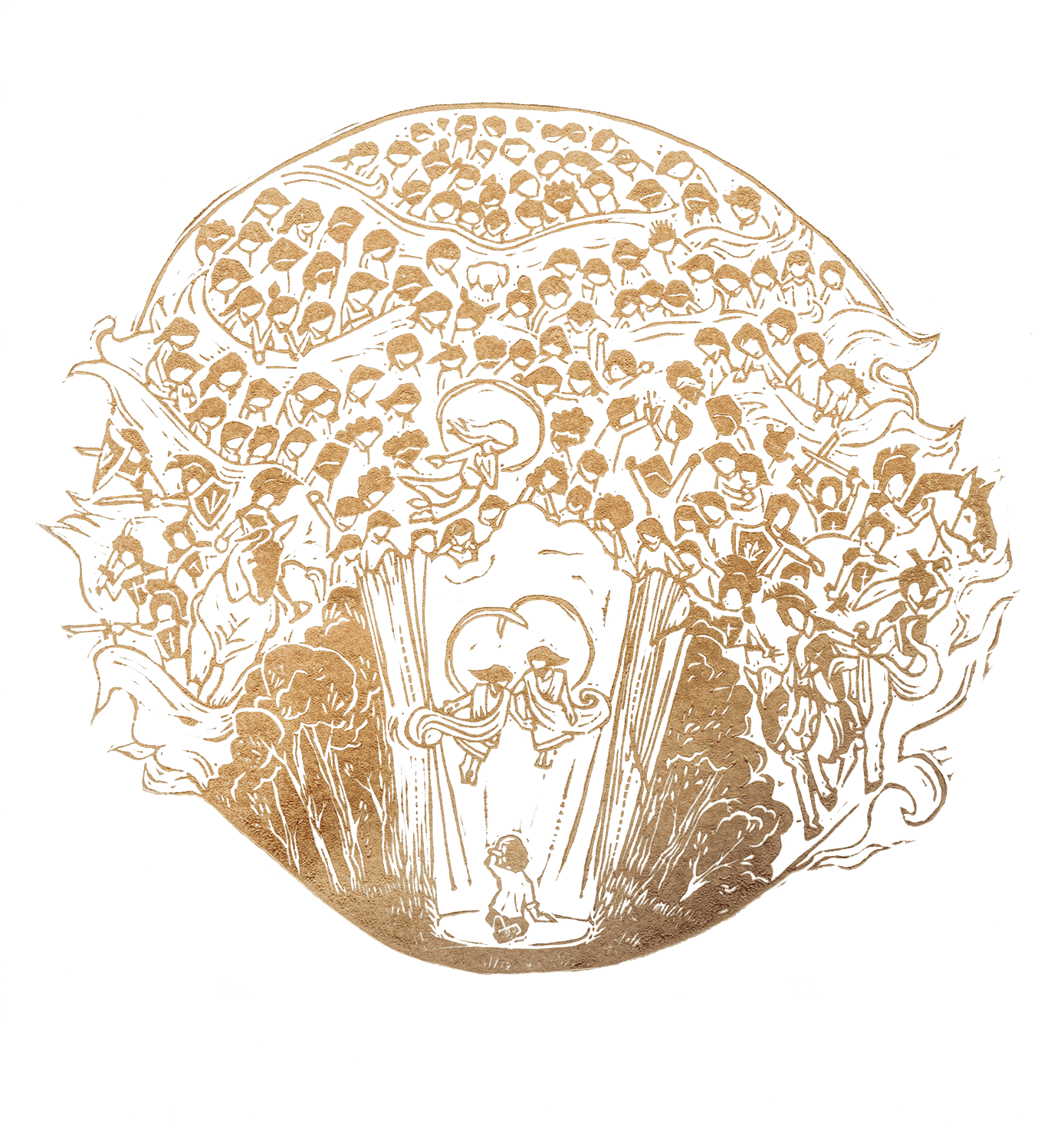

The 1838 account of the First Vision describes the struggle Joseph had with the adversary. At crucial turning points in the Restoration, Beelzebub, the enemy of righteousness, the prince of darkness, has made his power felt. The First Vision was a natural point of attack. The devil has not, like the rest of us, lost his memory of premortal life. He has not been placed in a physical body and had the veil drawn. He therefore knew Joseph Smith. Later in his life Joseph would say, “Every man who has a calling to minister to the inhabitants of the world was ordained to that very purpose in the Grand Council of heaven before this world was.” It is no surprise, then, that the adversary would wish to thwart the earnest supplications of the boy Joseph in the Sacred Grove. It was not the first time someone had prayed for the Lord to answer the hard question, “Where is the truth?” The response that came to Joseph was an answer, I believe, to millions of prayers offered down through the centuries on both sides of the veil.

How strong was the dark influence on that occasion? In the Pearl of Great Price account, Joseph makes clear that it was no imaginary thing. For a time it seemed as if he would be destroyed. In an earlier account he adds that for a time he could not speak, as if his tongue cleaved to the roof of his mouth. He exerted faith and was released from the evil power.

Fire, Light, Glory

Throughout his life the Prophet had important things to say about the power of the evil one, but he never said the evil one was as powerful as the living God. He knew both. Like Moses of old (see Moses 1:12–16), he was not confused when once he had experienced both and felt their influence. Speaking of the kind of power that we call possession, he taught the Saints that “the devil has no power over us only as we permit him.” But whether we are righteous or not, we do not escape the attacks. A healthy respect, if I may put it so, for the power of darkness arose from Joseph Smith’s early vision, as did a glorious respect for the power that overcomes darkness.

“Joseph described the descending light first with the word fire and finally with glory.”

Joseph described the descending light. In dictating the account, he sought the proper word. He first used the word fire. That is crossed out in favor of spirit or light. The word he finally settled on and used most often was glory. It refers to the emanating and radiating spirit and power of God. But the word fire is important to notice. Orson Pratt, in his book An Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions—published in 1840, two years before the Wentworth letter, and circulated widely in the missions in Great Britain and Europe—says that the young prophet expected to see “the leaves and boughs of the trees consumed.” In other words, he thought he was seeing descending fire, the kind that burns and consumes. Was that detail something Orson Pratt had learned from conversation with the Prophet? Or was it an inference from the statement Joseph makes that the “brightness and glory defy all description”? The Prophet indicates in the 1835 account that he was filled with that light, but also surrounded by it, that it filled the grove. Then he adds, “Yet nothing consumed,” perhaps indicating that he expected it to be.

The Prophet was not harmed by the experience; he was hallowed by it. Having seen the light, he now saw in it two personages, one of whom said to him, indicating the other, “This is my Beloved Son.” In the Wentworth letter the Prophet adds, speaking of the two, that they “exactly resembled each other in features, and likeness.” Notice they not just resembled—they exactly resembled each other in features and likeness. We speak of a family resemblance: “Like father, like son.” The Son looked like His Father. They are, in appearance as well as in nature, exactly similar.

This circumstance may give further insight into the phrase Alma used in his familiar set of questions about our spiritual progress: is “the image of God engraven upon your countenances?” (Alma 5:19). It gives further confirmation of the Prophet’s later vision of the Twelve while in Kirtland—a disparate group of men from a variety of backgrounds whom he saw in vision, through their flounderings and struggles, until he saw them glorified. He saw them welcomed by father Adam, ushered to the throne of God, greeted and embraced by the Master, and then crowned. “He saw that they all had beautiful heads of hair and all looked alike.” This should not be pushed to mean that the Twelve had absolutely similar features, but rather that in glory, “in bloom and beauty,” they were similar.

Young Joseph Smith learned in the Sacred Grove that to see the Father is to see the Son, and vice versa.

A deeper point is the relationship of these two beings. Joseph taught in the 1840s—and I think it was an extension of what he learned in the grove that morning—that the statement of the Master about His doing nothing but what He had seen the Father do has infinite implications.

If Christ Himself was uniquely begotten and was the firstborn in the spirit, and if He was the Christ not only of this earth but also, as the Prophet taught later, of the galaxy, so before Him the Father himself was a Redeemer, having worked out the salvation of souls of whom He was a brother, not a father. This is deep water. The conclusion is drawn by Joseph Smith in his King Follett discourse. Whatever else it may mean, and it is mind-boggling, it at least means this: The Father, by experience, knows exactly what His Son has been through. And the Son, by experience, knows exactly what the Father has been through. Therefore, when He says, “I and my Father are one,” He is not expressing a metaphysical identity. He is speaking of oneness of spirit, harmonic throbbings of love and insight that can come only in the patterns of eternal redemption. Sown in the mind of a 14-year-old boy, that seed of insight blossomed and grew.

Though we do not know how long the Prophet Joseph was in the grove that day receiving instructions, it probably was longer than is suggested by the outline we have. We know, for example, that he wrote, “Many other things did he say unto me, which I cannot write at this time.” So far as I know, he never did commit them to paper. Some critics have pointed out that the Prophet spoke of the visit of angels in connection with his First Vision. Some have theorized that he began by asserting that he saw an angel and ended by embellishing it with the claim that he saw the Father and the Son. The truth is that, having described all that we are familiar with about the visitation of the Father and the Son, he says in the 1835 account, “I saw many angels in this vision.” It is an enforced either-or to say that he either saw the Father and the Son or saw angels. What he saw was both.

“Having seen the light, he now saw in it two personages, one of whom said to him, indicating the other, ‘This is my Beloved Son.’”

The encounter, however long or short, demanded much. Joseph says, “I came to myself.” I think it inappropriate to say that he had been in a trance or a mystic state. The clearest parallels come from the ancient records of Moses and Abraham and Enoch. Like those prophets of old, Joseph was filled with a spirit that enabled him to endure the presence of God. Is that spirit enervating or is it energizing? My considered answer is, “Yes.” It is both. It demands from us a concentration and a surrender comparable to nothing else possible in this life. But it also confers great capacities that transcend our finite mental, spiritual, and physical powers.

In 1832, emerging from the vision on the three degrees of glory (D&C 76) with his companion in the vision, Sidney Rigdon, the Prophet looked strong, while Sidney was limp and pale. To this the Prophet, with a certain humility as also perhaps with a little condescension, said, “Sidney is not as used to it as I am.” But after the First Vision, as Neibaur reports, Joseph said “I . . . felt uncommon feeble.” It was difficult for him to go home.

The Character of God

We now turn to some of the theological extensions of this initial insight of the First Vision as the Prophet later taught them. “It is the first principle of the gospel,” he said, “to know for a certainty the character of God.” That is more than saying it is the first principle to know that God exists. He doesn’t use the word existence at all in this context. You can’t find one argument in Joseph Smith for the existence of God. Why not? One answer: Because one does not begin to argue about a thing’s existence until serious doubts have arisen.

Joseph wasn’t speculating. He was reporting his firsthand experience. Prophets always have. On the other hand, the philosophers have expended some of the greatest ingenuity of the western world in inventing what turn out to be specious and invalid arguments for the existence of God. No. “It is the first principle of the gospel to know for a certainty the character [the personality, the attributes] of God, and to know that we may converse with him as one man converses with another.” That is the testimony of Joseph Smith from beginning to end. He is talking about all of us, now. A man, a woman—it is the first principle for any of us. That is where we begin.

And lest we should say, as occasionally we do, “But his remarkable life and experience are utterly beyond my own,” we should note that Joseph said in 1839: “God hath not revealed anything to Joseph [calling himself by name], but what He will make known unto the Twelve, and even the least Saint may know all things as fast as he is able to bear them.” Even the least Saint, I repeat. The Prophet continued: “For the day must come when no man need say to his neighbor, Know ye the Lord; for all shall know Him (who remain) from the least to the greatest.” Note that “all shall know Him” is different from knowing about Him.

That same year Joseph delivered a marvelous discourse on the 14th chapter of John, that masterful sermon of the Savior’s in which He said that He and the Father would “make their abode” with faithful Saints. In this address the Prophet in effect readdresses that sermon to us. It is as if he said, “It is not enough for you to say, ‘Ah, Brother Joseph is in charge, and he knows.’ You must know.” He says it in 10 different ways. Then in the final part he says, “Come to God.” These blessings are intended for his Saints, so ask Him.

“Well,” one might feel, “I don’t want to overdo it. I don’t want to ask for things I shouldn’t ask for.” Of course, as a general principle that represents a genuine, discerning wisdom—we should not ask for what we should not seek from Him. But when the Lord has commanded us to ask, it is appropriate. This is illustrated in the Savior’s parable of the unjust judge and the importunate widow, which is preceded by the reason it was given—to show “that men ought always to pray, and not to faint” (Luke 18:1). It told of the widow who repeatedly came to the judge to plead her case. Always he refused to heed. But because she came back so often, in order to be rid of her the judge said, “All right! Give her what she wants and end her clamoring.”

What is the point of the story? Why would the Savior teach a parable like that? The point is, pray and don’t faint; or, in the words of Joseph Smith, “Weary [the Lord] until he blesses you.” There are places in modern scripture where the Lord commands someone not to pray further on a particular matter, where He says, “Trouble me no more.” But in each case the context shows He had already given the answer, and He is saying, “Please take no or yes for an answer.”

So it is. We have the privilege to recapitulate the Prophet’s experience.

That leads to my final point. So often we are haunted not only with the question of whether we have gone far enough in our own religious experience but also whether we can rely on some things we have previously trusted. Acids eat away at us. Sometimes it is the taunting of other voices; but sometimes it is nothing more than our own sins and weaknesses and the betrayals of the best in ourselves. Doubt naturally follows.

The Master made a strange statement to Thomas. Thomas is categorized as a doubter because he said what the others had said earlier: “I will believe when, and only when, I see.” According to Luke, the others virtually rubbed their eyes in disbelief when they did see. It is a beautiful phrase: “They yet believed not for joy” (Luke 24:41). Meaning what? Meaning it was too good to be true. Within days they had seen their Lord crucified, and now He stood before them! So they too had impending doubts, as did Thomas. The words of Jesus are reported by John: “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed” (John 20:29).

On the surface this statement seems to put a premium on secondhand or distant awareness, almost as if unsupportable faith is more commendable than faith resting on the knowledge of sight. That, I think, is a mistake. What is involved in the statement is the recognition by the Lord and by His prophets that the most penetrating of assurances—the one power, even beyond sight, that can burn doubt out of us and make it, as it were, impossible for us to disbelieve—is the Holy Ghost.

Filled with Love

Recording the feelings he had on leaving the grove and on the subsequent days, Joseph left on record this sentence: “My soul was filled with love and for many days I could rejoice with great joy and the Lord was with me but [I] could find none that would believe the heavenly vision.” This is one of the rare insights he gives as to what went on inside as distinct from outside him in that experience. Joy, love. And no doubt. Others, of course, doubted. He did not.

“We all can have the same glorious and glorifying certainty about the reality of the Father and the Son.”

The devil is shrewd with the strategems and with the Satanic substitute, but one thing he cannot counterfeit is the witness and power of the Holy Ghost. When that is upon us there is assurance—and, I repeat, even greater than that of sight. It is of course possible to have both, and that is precisely what Joseph Smith had. He saw, as a later revelation explains, not through the natural or the carnal mind but with the spiritual. He saw with his own eyes, but he also was enveloped in that radiating power that has been commissioned to bear witness of the Father and the Son. Without having open or remarkable visions, we all can have the same glorious and glorifying certainty about the reality of the Father and the Son; and that comes by the Spirit, by the power of the Holy Ghost.

Often we are confronted in the world by those who want to believe in God without believing in God. They are willing to affirm that there is something—and that’s about the strongest word they are willing to use—that there is something out there that accounts for things: a principle, a harmonic force, or an ultimate cosmic mystery. How rarely is the testimony welcomed that the Father is in the likeness of the Christ! One reason—and Latter-day Saints can testify of this—is that such personal beings can get involved in your life, changing it, giving specific commandments and counsels, rebuking, approving, or disapproving. A God who is utterly distant stays out of your hair.

It is unlikely that the Prophet fully anticipated the consequences of his prayer in the grove, but he nevertheless fully measured up to those consequences. He never wavered. On one occasion he said, “If I had not actually got into this work and been called of God, I would back out.” But he added—and this shows his integrity—“I cannot back out: I have no doubt of the truth.” From the grove experience on throughout his life he knew and welcomed into his life the Father and the Son, “even,” as he was commanded in 1829, “if [he] should be slain” (D&C 5:22). He was true unto life and unto death. To use the word that Joseph re-revealed in our generation, his integrity seals the power of his first and subsequent visitations. Anyone who has enough of the Spirit of God to know that God lives and that Jesus is the Christ, by that same spirit will be brought to recognize that one of the prophets called by the Father and the Son was Joseph Smith.

This is a condensed version of a lecture delivered by Truman G. Madsen, a former BYU professor of philosophy and the Richard L. Evans Endowed Professor, at BYU Education Week on Aug. 22, 1978. For the complete address and seven more lectures on Joseph Smith—with full notes and citations—please visit speeches.byu.edu.

© 1989 Truman G. Madsen

℗ 2003 Deseret Book Company

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. For personal, educational use only. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means outside of your personal digital device without permission in writing from Deseret Book Company, at permissions@deseretbook.com or P.O. Box 30178, Salt Lake City, Utah 84130.

Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.