Ask today’s BYU students what they know about Ernest L. Wilkinson, and it’s a good bet most of them will not be able to say much except that a major building is named in his honor. Yet Wilkinson, who was BYU’s president from 1951 to 1971, remains one of the most productive, colorful, and memorable characters who ever led the university. And as the man responsible for planning and building much of the BYU campus as it exists today, it is fitting that he be identified with a building.

“There is hardly any aspect of this university that does not bear the imprint of Ernest L. Wilkinson,” said Elder Dallin H. Oaks, who succeeded Wilkinson as president of BYU.

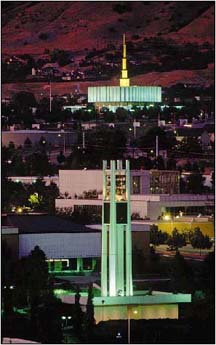

Wilkinson has been selected as the Founders Day honoree for Homecoming 1999, a week-long event that begins Oct. 4 and culminates Oct. 10. As alumni and friends of BYU converge in Provo for the celebration, they will find that while the campus continues to change through remodeling and expansion, Wilkinson’s thumbprint is still evident everywhere.

When Wilkinson was inaugurated in October 1951, the academic procession wound through a much smaller campus. Ceremonies were held in the newly completed but not yet dedicated Smith Fieldhouse. The Fieldhouse joined only five other buildings on upper campus that are still extant: the Maeser Memorial Building, the Grant Library, the Brimhall Building, Knight Mangum Hall, and the Eyring Science Center.

Student housing was equally sparse. Dormitory buildings, war surplus barracks, and co-op houses provided housing for only 1,259 students.

Wilkinson, who had been summoned from a flourishing law practice in Washington, D.C., to act as president, seized the opportunity for growth. During the 20 years of his presidency, the academic buildings on campus increased from only six on upper campus to 254 permanent and 85 temporary buildings–from 800,000 to about 5 million square feet of floor space. Student housing grew to accommodate nearly 6,000.

Wilkinson and his wife, Alice view the early stages of construction on the Wilkinson Center in 1960. The student center, which remains the hub of campus life, opened i 1964 and was extensively renovated between 1995 and 1999.

Nor was his construction at BYU limited to physical facilities alone. Wilkinson launched an aggressive recruitment program to attract students to BYU. When he left office in 1971, enrollment had multiplied six times, from 4,004 in 1951 to 25,116 in 1971. The full-time faculty had grown from 244 to 932, and those faculty with doctoral degrees increased from 50 to more than 500. Budget funds for the university had increased seven fold. The five original colleges with 37 departments had expanded to 13 colleges with 71 departments, associate and doctoral degrees had been added, and the quarter system had been changed to the semester system.

To Wilkinson, however, his greatest achievement at BYU was none of these.

In an interview with the Provo Daily Herald, he said, “If you were going to twist my arm until I named one single most important development with the greatest impact and influence, I would have to choose the establishment on campus of the wards and stakes of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The effects of the wards and stakes are more important and far-reaching than you might think.” In 1951 the campus had one branch; by 1971 there were 98 wards and 10 stakes.

It is no wonder, then, that upon his resignation, the Daily Herald editorialized, “Many labels will be given this energetic man by the BYU history writers. But perhaps none will be more appropriate than that of ‘University Builder.’ This one can go down in bold letters.”

Wilkinson was known as much for his personality as for his accomplishments. “It has been stated facetiously,” wrote Edwin J. Butterworth, who served as press relations director for BYU during Wilkinson’s tenure, “that when Ernest L. Wilkinson became president of Brigham Young University, he replaced the weather as a topic of daily conversation on campus. Actually, the observation is not overly exaggerated. The whirlwind of activity and stressed emotions created by the President, admirable in some minds and excessive in others, inevitably attracted the attention of all on campus and caught them up in its pressures. His extreme compulsion for unrelenting hard work in the transformation of the university, together with his blunt manner, sometimes jarred the academic community, although he was highly respected.”

In his history Wilkinson admitted that he was “too blunt, not tactful with people, and impatient with other people. If I sometimes offend people it is not because I want to, but because I am determined to get something done.”

Hard work and “getting something done” were the hallmarks of Wilkinson’s life. It was hard work that took him from his rough beginnings in Hell’s Half Acre in Ogden to Weber Academy, to BYU, to George Washington University Law School, and finally to a doctorate at Harvard Law School. Hard work characterized his years as an attorney in Washington, D.C., most notably in his representation of the Ute Indians.

Confederated Bands of Ute Indians v. United States was the first successful case brought against the federal government seeking recompense for tribal lands that had been taken but not paid for. Sixteen years of work resulted in a $32 million settlement to the tribes. It also led to the passage of the Indian Claims Commission Act, signed in 1946, which allowed all tribes to make similar claims. Seth Richardson, U.S. assistant attorney general, said in testimony, “The amount of service and research performed by Wilkinson and his associates almost staggers our imagination.” The U.S. Court of Claims found that Wilkinson’s firm had crowded 26 years of work into 16 years and awarded them legal fees of $2.8 million for their work on the Utes’ behalf.

Despite his achievements, one of Wilkinson’s great regrets was that he had not had an opportunity to serve a mission for the LDS Church. This regret was mitigated by his appointment as president, for he viewed his appointment to BYU as a mission. During 13 of his 20 years in office, he refused to accept a salary. Only when he returned to BYU in 1964 (after a brief hiatus for an unsuccessful attempt at the U.S. Senate), did he accept remuneration for his service to BYU.

His view of university service as a mission had its roots in an experience Wilkinson had when he first came to BYU–not as a student, but as a soldier.

In a personal interview with Butterworth, Wilkinson said, “I came first to BYU campus in 1918 during World War I in the uniform of my country. A dread influenza epidemic, with which our medical profession did not then know how to cope, spread throughout the two companies of soldiers quartered on this hill. The Maeser Building was the only academic edifice then in existence on the upper campus. I was one of the first stricken with that disease, which took more American lives than were sacrificed on the battlefields of France.

“As a fellow member of my company, who also held the priesthood, placed his hands on my head and blessed me that I would recover (and we all did), I promised my Heavenly Father that if he would spare my life, I would serve this institution if ever the opportunity presented itself. Little did I realize that about 30 years later I would be appointed president of Brigham Young University, and that my office would consist of the room where I was restored to health. I humbly hope that in that capacity I have kept my promise.”

In his book I Remember Ernest, Butterworth concluded, “He did, abundantly.”