For BYU Homecoming 2023, descendants of George H. Brimhall sponsored an essay contest honoring BYU founder Martha Jane Knowlton Coray, the first woman on the board of trustees for the fledging Brigham Young Academy in 1875. Life-sciences student Erika E. Frandsen (’24) penned the winning essay, published below.

The first important fact to be known is that I liked this boy. As in, a lot.

There we were, sitting in his car, and I teasingly asked him what he really thought of me. He turned toward me, considered, and said, “Honestly? Sometimes you’re a little much.”

This was not the first time I had been told I was “too much,” and it wouldn’t be the last. Other descriptions I’ve been awarded include “oppressively friendly” and “incredibly loud.” And truthfully, I sometimes say it to myself as well, joining the ranks of those telling me to calm down, rein it in, and be less.

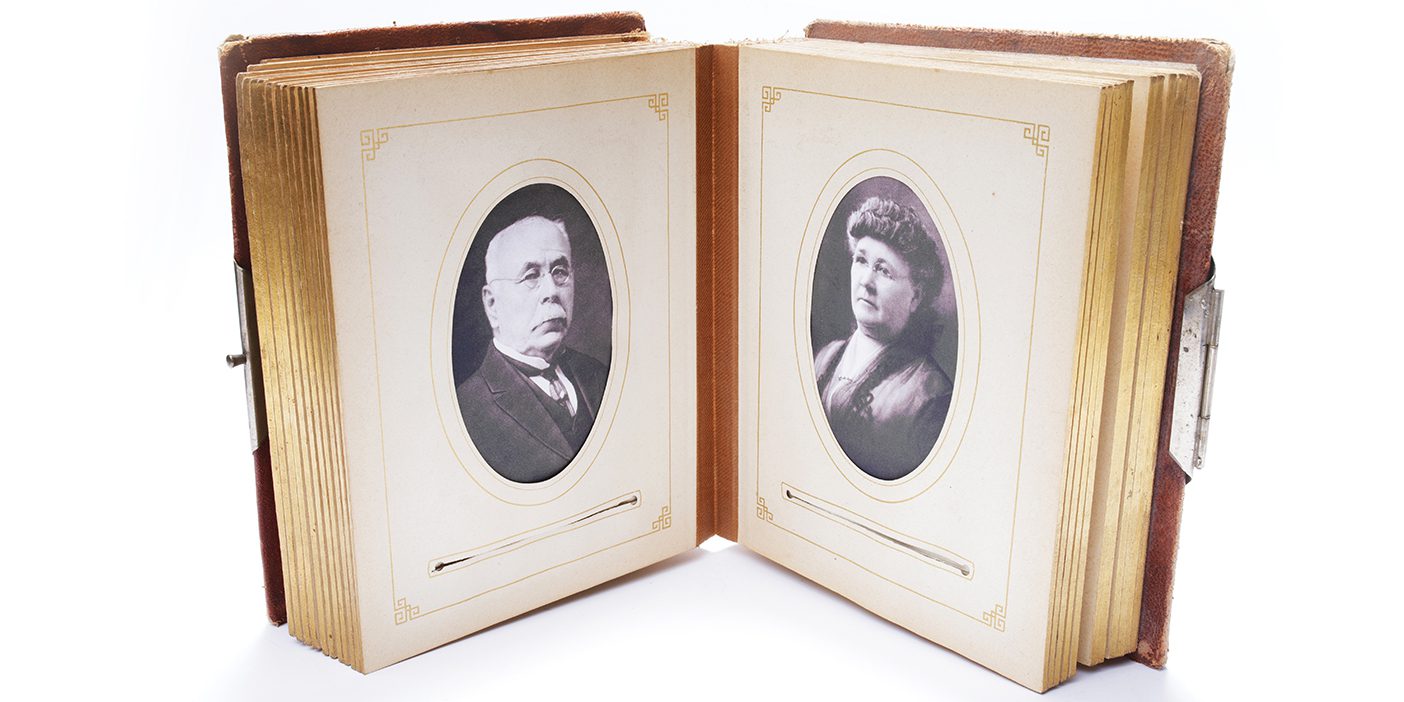

When reporting Martha Jane Knowlton Coray’s death in 1881, the Salt Lake Herald described her as “possessed of indomitable energy.” The line made me wonder if Coray, as a woman with “indomitable energy” living in a deeply religious community in the 1800s, ever felt like she was “too much” as well. To be fair, she was a lot. She wrote newspaper articles, she helped Lucy Mack Smith write the biography of her son Joseph, and she served as the first Relief Society secretary in Salt Lake City. She taught at several schools and operated her own still to make oils. She was self-educated in law, and when Brigham Young Academy formed its first board of trustees, she was its sole female member. And she did all this in addition to being a wife and a mother of 12.

A woman living in that time with all those skills, juggling all those responsibilities, must have felt conflicted sometimes. It almost feels like there were too many sides of her to focus on. As I read and researched, I felt torn between wanting to write about what a good mother she was and how diligently she served in her church callings versus how knowledgeable and driven she was in academia and industry. However, focusing on just one or two aspects of Coray wouldn’t do her justice. She wasn’t just a trustee, and she wasn’t just a wife and mother. She wasn’t just a teacher, and she wasn’t just a Relief Society secretary. It was the combination of all those things—and more—that made up who she really was.

And who she was was not the stereotypical 1800s housewife. In her letters to her future husband, Howard (written while they were dating), she was forward and assertive at a time when meekness in women was praised. When women were expected to be agreeable, she was described as having “a will of iron.” She educated herself about the subjects in which she was interested, including chemistry and law, then passed that knowledge down to her children. But did she ever wonder how she could be an ideal woman of God while still being true to herself—assertive, determined, and ambitious?

I wonder this all the time. Sometimes it seems the ideal woman of God is not at all who I am. I feel conflicted trying to reconcile all the parts of my identity. When I received a call to be the president of my ward Relief Society, I wondered how I could possibly fill that role. It seemed to me that responsibility should go to someone with lacy tablecloths, cute handouts, and a sweeter and softer manner. How could I—talkative and stubborn and enthusiastic—be that person?

Well, how did Martha Coray do it? She was able to be a woman of God, a good mother and wife, and an unconventionally successful person because she leaned in with all of herself, never just part. She didn’t dim down for others—she was always every bit herself, even when others may have seen it as too much. She pursued what she cared about while also fulfilling her covenantal responsibilities—and she did it all while being herself: smart, loving, undaunted, and highly energetic.

If part of ourselves is always hidden or unacknowledged, we will never be truly illuminated. Standing in the light and being shown to the world requires leaning in, like Martha Coray did, with all of who we are.

Even if all of who you are is too much for some people.