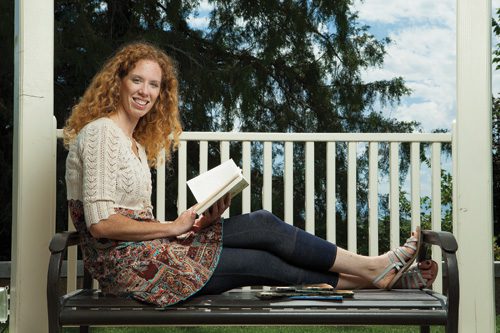

Kirsten E. Dekker (BM ’02) arrives on the school floor early, retrieves a cart stacked with student folders and teaching supplies, and puts on her mandatory blue smock. It’s not flattering—it’s not meant to be.

“I like my smock!” she protests. It’s an unusual outfit for a social studies teacher, but then the high school on Rikers Island is an unusual school, situated at the world’s largest penal colony on an unloved island in Flushing Bay, Queens, N.Y., just off the runways of La Guardia.

The sleepy-eyed students arrive at the gate an hour late. The first two jostle each other a bit until they see a reporter at the end of the hall, surrounded by three of New York’s Boldest (and beefiest). Word spreads quickly, soundlessly. Two become six become twelve, clustered in a tight semicircle. Whispers. Their eyes are now like saucers, full of feral intensity, absorbing every bit of available information.

Minutes later Dekker stands in front of her class, a little too bright and cheery for someone who got up at 6 a.m. and took three trains and a bus to get to work. She reminds the students about the upcoming end-of-school-year Field Day and circulates a sign-up sheet for the ice cream–eating contest. She gives a quick motivational speech about tomorrow’s Regents exam (students must pass five subject areas to graduate high school). “I’ve seen people get 25 out of 50 and still pass,” she tells them. The students hardly seem to hear her. Finally, one speaks.

“Miss, they gonna have real ice cream there, Miss?”

Yes, she reassures, the ice cream at Field Day will be real. The idea of the contest, she explains, is to eat it as fast as you can.

Another student speaks up, almost offended: “I’m-a take my time.” He mutters it again to himself. “I’m-a take my time.”

“They’re like babies,” Dekker says later with evident affection. Babies awaiting trial or sentencing for top-level felonies: murder, armed robbery, rape.

The average length of stay is 48 days. “It’s hard—students just disappear,” Dekker says. “I had an excellent kid, had him since September—he went upstate. You can’t say goodbye. You can’t keep in touch. I wish there was a way to track them better.”

The morning class contains her best students. Her afternoon class will not be taking the Regents exam. “Most of the time I’m just breaking up gang meetings,” she says of that class. The majority of students are below a 9th-grade level; some are illiterate. Dekker tutors them one-on-one whenever she can.

Walking past another classroom, Dekker points out the students in the back row—all sound asleep, their shirts pulled over their heads. Students who sit at the back of the class are generally the alphas, while those in front are the ones who get extorted, she explains.

“I’ve only had four or five fights this year,” she says. “The turtles [corrections officers in riot gear] come in and take care of it, but that’s the end of class—if there’s an alarm, everyone goes back to the cells.” One morning she was greeted with a puddle of blood outside her classroom; just yesterday she returned to her class to find someone had tipped her cart, spilling folders all over the floor and knocking over her basket containing confiscated contraband and school supplies that can be made into weapons or used to get high.

“I’ve only had four or five fights this year,” she says. “The turtles [corrections officers in riot gear] come in and take care of it, but that’s the end of class—if there’s an alarm, everyone goes back to the cells.” One morning she was greeted with a puddle of blood outside her classroom; just yesterday she returned to her class to find someone had tipped her cart, spilling folders all over the floor and knocking over her basket containing confiscated contraband and school supplies that can be made into weapons or used to get high.

Does Dekker feel safe? “Are you kidding?” she says. “I taught in the South Bronx—it’s the same population, except there if there’s a fight, you’re on your own. Here I’ve got an officer in the class with pepper spray.” The students tell Dekker they also prefer the school at Rikers for the same reason. As Capt. Sean Jones, of the NYC Corrections Department, explains, “They know they’re not going to get slashed or jumped. It’s a protected environment.”

So how did Dekker, who graduated with a degree in music education and got a master’s from Teachers College at Columbia University, end up teaching at a prison? Her plan was to teach music history and piano in Orange County, Calif., where she grew up. But a student teaching job in East Harlem led to the South Bronx position, working with students who were on the verge of dropping out. While her class was a success, the program got cancelled. Dekker did the logical thing and accepted a job teaching music appreciation in a good Manhattan neighborhood, but she soon discovered she missed working with high-needs students. After coming out of the interview for the Rikers job, she called her mother and asked, “Is it weird that I feel completely comfortable in jail?”

“I like working with guys that everyone else has given up on,” Dekker says. “The highs here are higher than they are on the outside—when the guys get it, when they’re excited about something . . .” She doesn’t finish the sentence, doesn’t need to. “But then the lows . . . ” she laughs. “Back in September we were really struggling—it was rough. At times I was ripping my hair out.”

“It was a bit of a shock for her,” assistant principal Andrew Brown says of Dekker’s initial arrival at the school. “But she came every day. She worked really hard. And she grew to love the population she’s working with. She’s been a huge part of making the program better.”

The alphas in the back row of Dekker’s class are more concise in their praise. “She’s a good teacher,” says a burly kid they call Smalls. By comparison, the next guy is loquacious: “She take her job serious, more than the other ones.” And that’s that—end of interview.

One student sits to the side, his desk perpendicular to the rest of the class—neither alpha nor extorted but apart, his position seems to say. He actually wants to speak about school, about his teacher. In a whisper he says:

“You’re not incarcerated when you’re in here. She makes you want to learn—not every teacher have that. She push you. Some just say, ‘Put your head down.’ Ms. Dekker, she’s the  one told me, ‘It’s never too late.’ I learned tons of things from her, educational-wise, and not just social studies—she’ll dip in a little math, dip in a little science, she bounce around. She’s an excellent teacher. I already got my GED but I’m not gonna let my time here be in vain—gotta get something out of it. Might as well learn something new. Education is endless.”

one told me, ‘It’s never too late.’ I learned tons of things from her, educational-wise, and not just social studies—she’ll dip in a little math, dip in a little science, she bounce around. She’s an excellent teacher. I already got my GED but I’m not gonna let my time here be in vain—gotta get something out of it. Might as well learn something new. Education is endless.”

This kid knows what many college graduates don’t. How did he land at Rikers? Although he has been in her class for the entire school year, Dekker has no idea what he was charged with.

“These students all walk around with labels, almost like it’s written on their foreheads—Bloods, Crips, the crimes they’re charged with. For some it’s a matter of pride,” Dekker says. “The Savior doesn’t see any of us with labels. We could all walk around with labels on our foreheads for the things we’ve done. I see them as my boys, my kids.”