The Museum of Art’s new exhibit explores ever-evolving ideas about America and its people.

On Jan. 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy uttered his now-famous line “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” Less famous is what the poet Robert Frost said next. After concluding, the president introduced Frost, who was to read a poem he had written for the occasion.

Taking the podium, the 87-year-old poet squinted into the glare from new-fallen snow on the Capitol grounds, unable to make out the poem in front of him. Improvising, Frost recited from memory “The Gift Outright,” a poem he had written some 20 years earlier:

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

[The Poetry of Robert Frost, ed. Edward C. Lathem (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1967), p. 348]

The sweep of Frost’s poem is the sweep of American history: promise giving rise to boldness, violence, westward expansion, new beginning. It contains elements that, together, give us our sense of the “American Dream,” however vague or evolving that notion may be.

American Dreams, the BYU Museum of Art’s new exhibit from its permanent collection of American art, tracks variations on this theme. Through the visual expressions of 18th-, 19th-, and 20th-century artists, the exhibit demonstrates the changing, and at times conflicting, ideas of America and what it is to be American. Exploring broad themes, the exhibit is split into three parts: the Dream of Eden, American Aspirations, and Envisioning America. With 115 pieces on display at a time, works will rotate in and out of the exhibit during its five-year run. More than 200 works will be part of the presentation.

This article presents a sampling of the paintings and sculptures in the exhibit, coupled with the words of leaders, writers, and poets about America, “such as she was, such as she would become.”

WEB: To see more images from American Dreams, visit the Museum of Art Web site—moa.byu.edu.

INFO: The American Dreams exhibit is presented on the main and lower floors of the Museum of Art.

Envisioning America

Perceptions of American identity derive in part from its founding stories, which are at times confirmed and at times challenged by the realities of American life. In their works, American artists suggest various roles for the nation—from the inheritor of classical Western ideals to a bastion of freedom to a crucible of unresolved tensions.

I always consgrand scene and design in providence, for the illumination of the ignorant and the emancipation of the slavish part of mankind all over the earth.

—John Adams (1735–1826)

The gap between ideals and actualities, between dreams and achievements . . . is the most conspicuous, continuous landmarkin American history . . . not because Americans achieve little, but because they dream grandly. The gap is a standing reproach to Americans; but it marks them off as a special and singularly admirable community among the world’s peoples. —George F. Will (b. 1941)

American Aspirations

Long tied to attainment—of refinement, comfort, leisure, beauty—the American Dream has been a motivating force throughout the nation’s social strata. That dream has been perpetuated through artists’ depictions of the fashions, material goods, and entertainment enjoyed by the upper classes of society.

Conspicuous consumption of valuable goods is a means of reputability to the gentleman of leisure.

—Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929)

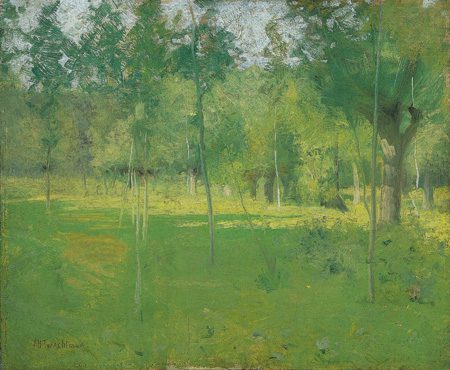

The Dream of Eden

For many settlers of America, the land seemed an endless frontier, a pristine wilderness of pastoral simplicity and limitless opportunity. As that frontier diminished and the land’s native peoples were displaced, however, the longing for a lost Eden became a broad theme in American consciousness and art.

For this is what America is all about. It is the uncrossed desert and the unclimbed ridge. It is the star that is not reached and the harvest that is sleeping in the unplowed ground.

—Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–73)

We know that the white man does not understand our ways. One portion of land is the same to him as the next, for he is a stranger who comes in the night and takes from the land whatever he needs. The earth is not his brother, but his enemy, and when he has conquered it, he moves on.

—Chief Seattle (1786–1866)