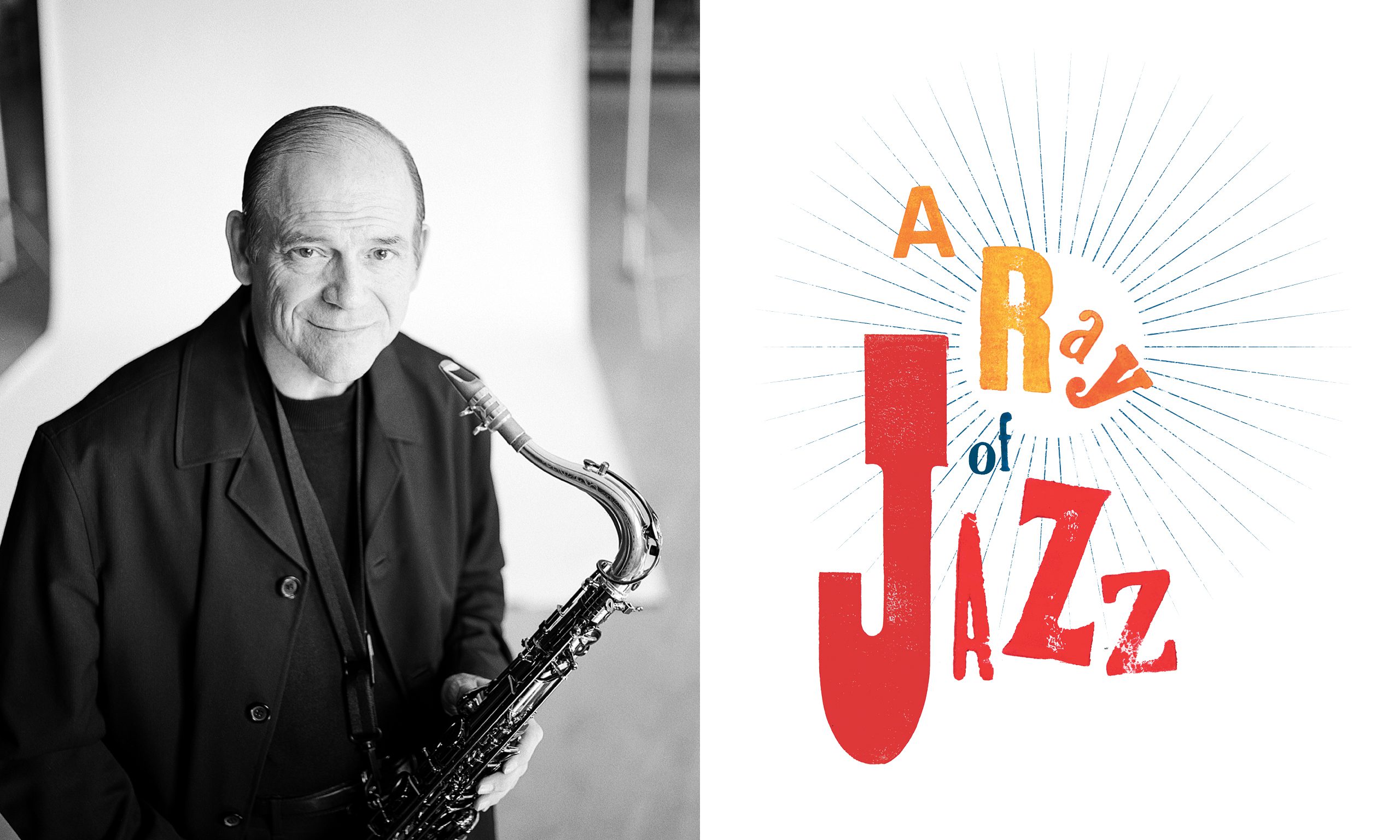

A Ray of Jazz

Band director, mentor, and performer of dozens of instruments—Ray Smith has combined his talents for 25 years to make space for jazz at BYU.

By Nathan N. Waite (BA ’07) in the Fall 2007 Issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

Ray Smith (BM ’75) is playing only four instruments tonight.

At the moment, he’s on the clarinet accompanying Jean Valjean, who is standing somewhere above the orchestra pit praying to God to bring Marius home. As he plays the last note of the song, Smith is already unhooking the instrument from his neck. The conductor signals the cut-off, and Smith sets down the clarinet while simultaneously reaching for his flute. Glancing again at the music score, he shakes his head and grabs the piccolo instead, just in time to signal the next battle scene of Les Misérables.

When a longer pause in the music comes around, he grumbles, “No time to read a book down here,” but then smiles as he picks up the alto saxophone for the wedding scene. The score is marked “schmaltzy.”

Ray Smith can do schmaltz. Ray Smith can do a lot of styles, actually. Last Saturday he was part of a jazz quartet, improvising lively Latin riffs in front of an upbeat crowd. He regularly sits in with the Utah Symphony. Next week he’ll perform with a Celtic band.

“It’s all about being diverse and eclectic,” says Smith, who has taught jazz and woodwinds at BYU for 25 years. “That’s been me from the beginning.”

Woodwinded

Smith started out on the clarinet in fourth grade and soon branched out to the saxophone, but that wasn’t enough for him.

“I had polio when I was 3,” explains Smith, who today walks with two leg braces and a cane. “I didn’t do sports, so I had more time for music.” After one of many surgeries in middle school, he found himself in a body cast up to his chest. “I couldn’t sit up, and it was really difficult to play clarinet and saxophone, so I learned the flute because I could do it lying down.” By the end of the summer, he could play along with all the TV commercials and radio tunes.

Each summer during high school, Smith dedicated himself to more and more practice, increasing his sessions from two hours to three, then to four. In his senior year at West High School in Salt Lake City, Smith played first chair alto sax in the jazz band, first clarinet in the concert band, and first flute in the orchestra. Before his freshman year at college, he practiced six hours a day for about a month. “It was killing me,” he says, “so I dropped back to four.”

After serving in the Montana-Wyoming Mission and earning a bachelor’s degree in music education from BYU, Smith received his master’s and doctorate in woodwind performance from Indiana University, picking up more instruments along the way. His saxophone instructor was Eugene Rousseau, considered by many to be the best classical saxophonist in the world. “In my 36 years at Indiana University,” says Rousseau, “Ray is one of only three people who played a recital on all five woodwind instruments—that’s going on stage and playing a sonata on the flute, clarinet, oboe, bassoon, and saxophone. That is a tremendous achievement.”

With a mostly completed doctorate in woodwind performance and a growing family—he had married Debbie Nelson, and the couple had two children—Smith took a teaching position with Murray State in Kentucky but had his sights set on teaching in the School of Music at his alma mater. He applied again and again for BYU faculty positions, but after seven applications, he had heard nothing back.

During that time, Smith struck up a backstage conversation with famed tuba player Harvey Phillips, who encouraged the young musician to consider a recording career in New York City. “I’ve always loved recording,” Smith confides. “When Harvey offered to introduce me to the right people, the idea got hot in my blood. Debbie even agreed to go for a little while, though she had never wanted to live in New York. I thought, ‘Maybe this is what the Lord wants me to do.’” He started planning for a career change.

But then, in March 1982 after three years at Murray State, Smith received a phone call from James A. Mason (BA ’55), the soon-to-be dean of Fine Arts and Communications at BYU: “Ray, we’re expecting you here this summer. What can we do to help you make the move?”

Smith recalls, “Inside, I was thinking, ‘Um, uh . . . maybe it’s not that simple anymore.’” He got off the phone and went to his knees, praying for direction. The answer came, and it wasn’t long before the Smiths were on their way to Provo.

Key in bringing Smith to campus was his BYU mentor, K. Newell Dayley (BS ’64), who had worked for several years to build a jazz program at BYU before being named the director of the School of Music. Dayley saw Smith as an ideal replacement. “As a performer, he’s just awfully unique,” says Dayley. “You name the instrument—he plays it, and he plays it well.”

The Doubler

Smith is, in music parlance, a doubler—a jack-of-all-trades who can pick up any number of instruments and play them masterfully. “There are very few in the country who can do what he does,” says J. Daron Bradford (BM ’80), a fellow doubler and a part-time faculty member in the School of Music. “Ray is the top doubler in the state, hands down. He could go to L.A. and be among the top five there.” Closer to home, Smith has played more woodwinds—all except piccolo and contrabassoon—with the Utah Symphony than any other musician.

Just how many instruments does he play?

Start with the A, B-flat, and E-flat clarinets—“though I don’t play the E-flat much,” Smith says—bass clarinet, and contrabass. Add the four saxophones. And the four flutes and all the recorders as well as ethnic flutes, such as pennywhistles, Chinese flutes, Japanese flutes, and the South American quena. Then jump across the orchestra to the double reeds, including oboe, English horn, bassoon, and contrabassoon. Smith also learned to play some very old instruments at Indiana—such as the Renaissance-period krummhorn and shawm. And he specializes in some of the newest, including the Yamaha WX7, an electronic wind instrument connected to a synthesizer. The complete tally (though he has never bothered to count) is probably in the 30s.

“He could have made it in New York as a jazz performer or played in one of the top symphonies in the country.” —Steve Lindeman

Smith’s performance ability isn’t limited to doubling. Music professor Steve Lindeman says that, had Smith made other choices, “he could have made it in New York as a jazz performer or played in one of the top symphonies in the country.”

Lindeman recalls giving a preconcert lecture to a Salt Lake City audience who had come to hear legendary jazz pianist Chick Corea. “It was kind of a sleepy crowd,” Lindeman says. “I’m telling them, ‘Chick Corea has played with people like Miles Davis.’ And the crowd is asleep. ‘He’s, uh, won 27 Grammys . . .’ Nothing. ‘And, you know, he’s unquestionably one of the three greatest jazz pianists in the world.’ I’m hearing snores. Then I mention that I have a recording of Ray Smith playing a Chick Corea tune,” laughs Lindeman. “And that’s when the crowd gets excited. Here I’m talking about the gods of jazz, and I mention Ray Smith and it’s like he’s a rock star.”

Smith has played with Ray Charles and Barry Manilow, and he is constantly recording for network television and national and international films. For many years, the nation woke up to his saxophone playing on Good Morning America. He says, “There have been times when I’ll be watching the news or get in the car and turn on the radio and think, ‘That’s familiar; I must have this CD. What is this?’ And then I realize, ‘Oh, that’s me.’”

“He comes to his playing from both sides—classical and jazz—simultaneously,” says Dayley. “You could call him bilingual. He speaks both languages.”

For Smith, though, there’s only one language. “I just love music. For me, all the style demarcations are really not there. I feel like it’s all one.”

Spirited Music

Smith came to BYU mainly to take over the university jazz ensemble, Synthesis. Dayley had worked for several years to build a jazz program at BYU, and when Smith took over, the band had been around for over a decade. Yet many in the community and even at the university still dismissed jazz as, at best, an unsophisticated art form and, at worst, an immoral and evil influence.

“Jazz has long been associated with evil environments and evil lifestyles,” says Smith. But he has a different take.

“I frequently whistle,” he says with a smile. “You know, the music’s in my blood. I’ll walk into the HFAC whistling a bebop tune or something, and I’ve never had anyone come up and say, ‘Well, how come you’re so sad?’ It’s always, ‘Wow, you’re happy today!’ Jazz is cheerful, uplifting music.”

It has been a struggle, at times, to convince others. Smith recalls a conversation between two BYU students after he received a new church calling: “What’s this world coming to when a jazz musician can be made a bishop?” But Smith believes the Spirit can be conveyed through the toe-tapping music. “In graduate school, I’d be sitting in the middle of a jazz class, and I’d feel the burning of the Spirit so powerfully and it would puzzle me,” Smith recalls. He later found quotes by Brigham Young about the duty of the elders of the Church to gather truth from whatever source and bring it back to Zion. “I felt I had that mission to a certain extent—to bring to Zion the wonderful aspects of jazz and practice them in a wholesome lifestyle.”

Smith has managed to show that not all jazz musicians fit the immoral stereotype—some raise eight children and serve faithfully in the Church. “Ray has a profound faith, and he’s really a model Christian,” says Lindeman. “He is able to very convincingly show that the music’s got nothing to do with an unseemly lifestyle, that the music stems from Heavenly Father, a manifestation of all things good on the earth—passion and joy and power and romance and heartbreak.”

Along the way, Smith has led Synthesis to international acclaim. In addition to playing all over the United States, the band has toured Western Europe, Asia, Russia, and Scandinavia. Smith’s office walls are plastered with posters of prestigious jazz festivals and famous players Synthesis has shared the stage with, such as Maria Schneider, Michael Brecker, and Bob Mintzer. In 1998 Synthesis became the first American big band to tour Siberia. In 2001 the band was hired to perform as the Harry James Orchestra for a week, playing big-band tunes aboard a cruise ship. The band’s director and singer fronted Synthesis.

The most important work Synthesis does on tour, according to Smith, is spread the gospel. While some may balk at the idea that testimony can be borne through jazz, Smith has seen it again and again: “You would really be surprised if you could see it in action. Often I have people come up after a concert and say, ‘There’s something that comes from this stage when they play, some kind of love or something.’ They don’t know how to say it’s the Spirit.”

Debbie Smith has accompanied her husband on tours across the globe. “I’m always so impressed with how wonderful and receptive the people we meet are,” she says, adding that many missionary contacts and lessons have come from Synthesis tours.

Back home, Synthesis has also gained a reputation, and not just for jazz. “Over the years, people have come to the show just to see how we’ll come onto the stage,” Smith admits. The famed entrances are becoming the stuff of urban legends in the HFAC: band members riding in on roller skates, piling out of a VW Beetle, crowd-surfing from the back of the auditorium in a rubber raft. Once Smith even arrived in a sarcophagus. “They brought it in on a forklift, opened it up, and I came out, all wrapped in toilet paper, playing my sax.”

Champion of the Underdog

Smith has done more than simply help strip jazz of its taboo status. According to School of Music director Dale E. Monson (BA ’75), “What’s unique is his dedication to jazz as a curriculum, as an idea.” Central to jazz playing is improvisation—composing and creating on the fly—which Smith sees as “the lifeblood of the music.” By doing more than simply reading notes on the page, he says, musicians take responsibility and actually create music. He traces this line of thought back through the likes of Beethoven, Mozart, and Bach—“some of the greatest improvisers in history.”

When he arrived at BYU, however, Smith’s views seemed almost heretical. “I felt like I was totally the underdog, like almost no one else championed these ideas,” he says. With the support of Dayley, then directing BYU’s music program, Smith slowly worked on introducing improvisation.

“I remember the first time I had a saxophone student play jazz for a faculty jury,” Smith says. “He played a Charlie Parker solo, and then he continued to improvise after [Parker’s] solo was over. I was sweating bullets the whole time, thinking the faculty was just going to blast me for letting this happen.” When the student finished, the panel thanked him and he left. There was a moment of unbearable silence before one of the faculty members finally spoke up, saying, “I wish I could do that.” Another added, “Yeah, me too.” Smith says, “And I thought, ‘Whew! We made it!’” Further work by Smith and others brought about an improvisation class and eventually a jazz-studies major.

Just like jazz, the saxophone has struggled to gain respect. “It’s seen as an illegitimate child of music,” says Smith, who was the first saxophone instructor hired at BYU. Since then, the saxophone program has blossomed. “He’s brought artistry to the saxophone, both in classical music and jazz,” says Dayley. “He raised the status of that instrument way up.” Smith now teaches a dozen students every semester, and the school has hired a second saxophone teacher.

As a saxophone instructor, Smith has lived up to his prestigious pedigree. His instructor, Eugene Rousseau, studied with Marcel Mule, the second saxophone instructor at the Paris Conservatory (the first was Adolph Sax himself). Mule helped design the Selmer saxophone, the pinnacle instrument at the time. It was Rousseau who did all the consulting on Yamaha’s line. Continuing the tradition, Smith has been influential in the development of Cannonball saxophones, a highly respected brand created by Smith’s fellow Synthesis alum, Tevis R. Laukat (BM ’79).

The Teaching Gig

Smith’s abilities as a doubler and wide range of experience have made him a unique teacher. According to Monson, “Ray engenders an enormous respect from his students, who see someone who not only tells them what to do but shows them how to do it.” In rehearsals, he’ll often pull out his saxophone and play a line or two to demonstrate a feel or a technique. “And he has a lot of lessons about the real performance world,” comments saxophone performance major Justin R. Knapp (’12). “He’ll tell all kinds of stories about gigs he’s done, and it really helps you prepare for the real music world.”

“Smith shows his students what can be done. They rise to the level of expectation.” —Daron Bradford

Smith’s work as a teacher is mainly done one-on-one. “He has players in his office all the time,” says Skyler J. Murray (’09), saxophone performance major. “Even with a trombone player or something. He’ll have them in his office for 45 minutes, working through a solo.”

According to fellow doubler Bradford, Smith is “showing his students what can be done. They rise to the level of expectation.” His students have gone on to successful careers as college professors, Hollywood film scorers, and, yes, professional doublers. Former students even get some of the gigs he used to take.

Rachelle Reid (BM ’07), who was mentored by Smith, now teaches middle school band and orchestra and says she learned more than how to play the saxophone from her teacher. “Everything had a greater purpose for Ray. He wasn’t just teaching me music, he was teaching me how to be a better person and how to become dedicated to what I do. He always made sure things were going well in all areas of my life, not just if I was practicing.”

The Fourth Musketeer

Smith recently released a landmark album on Tantara, BYU’s recording label. Titled Tableaux de Provence, it’s a solid hour of classical saxophone music. In his praise of the recording, Eugene Rousseau said, “Ray Smith has earned his place as one of the world’s outstanding woodwind artists.”

The album underscores Smith’s success in bringing diversity to BYU music, and one track in particular dramatizes the struggle—Pierre Max Dubois’ The Three Musketeers. In the piece the swashbuckling friends are portrayed by the traditional reed trio: oboe, clarinet, and bassoon (all played by Smith and overdubbed, in this case). As in the legend, a fourth member wants to join. “In the piece, the fourth musketeer is the alto saxophone,” explains Smith. “He has to prove his worth.” By the end of the final movement, it’s clear that the saxophone has made a vital contribution to the reed family.

In 25 years Smith has helped make jazz’s contribution to BYU clear. “When I started here, there were only one or two other faculty members who shared my views,” Smith says. “Today a faculty meeting about jazz studies is well-attended by many faculty members. There’s really a lot more open-mindedness about other styles now. I’m thrilled to be a part of that.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.