Buried for years in a library behind the Iron Curtain, a once-neglected concerto manuscript now tells the tale of the development of a young genius and a musical genre.

He was a boy genius. Some compared him to the young Mozart. Some said he was better. He completed his first full-length work when he was 11 years old. By the time he was 14, he had written five concertos and 12 symphonies, among other “exercises.” He wrote one of his most beloved pieces—Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream—when he was 17. He is said to have reached musical maturity earlier than any other composer.

A footnote in a 1960s publication sent Stephan Lindeman on a quest to discover the story of a pair of early-19th-century musical manuscripts. The documents he found led to the world premier of a 200-year-old concerto and revealed how Felix Mendelssohn, a master composer, revised his work, developed his style, and shaped a musical period.

And almost 200 years later, Felix Mendelssohn is still having world premiers.

Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg in 1809 to a prosperous banking father and an artistic mother. When Mendelssohn was young the family moved to Berlin, where his gift as a musician and composer was nurtured by the best teachers Berlin could offer.

Adolescence was a prolific time for the precocious Mendelssohn. In 1823 he wrote a two-piano concerto as a birthday gift for his sister Fanny, also an accomplished musician and composer. The siblings first performed the three-movement concerto at one of the Mendelssohn family’s Sunday musicales. Though Mendelssohn would perform the concerto a few more times, it eventually was set aside as a youthful exercise. The unpublished score was left among his stacks of papers and manuscripts when he died in 1847.

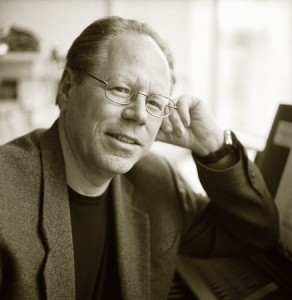

Almost a century and a half later, the concerto attracted the attention of Rutgers PhD candidate Stephan D. Lindeman, now an associate professor of music theory at BYU, and set him on a decade-long path of search and discovery. What he found has given the music world a rare glimpse into the compositional process of a musical genius and insight into the evolution of the Romantic period of music. The quest culminated in a 21st-century premier for one of the 19th century’s most celebrated composers.

The Footnote

Lindeman’s quest started with a footnote.

In 1878 Mendelssohn’s manuscript of the two-piano concerto was transferred, along with the majority of his other manuscripts, by his heirs to the German State Library. Paid little heed in a late-19th-century publication of Mendelssohn’s works, the manuscript was the subject of more intensive study only in the mid-20th century by German scholar Karl-Heinz Köhler, who published the work in the early 1960s as the Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra in E Major.

Köhler mentioned in a footnote that there was one other surviving score, a copy handwritten by Ignaz Moscheles, a 19th-century virtuoso pianist and a friend of Mendelssohn. Moscheles’ copy had also made its way to the German State Library in Berlin, but Köhler made the logical choice to focus his efforts on the composer’s own highly revised manuscript.

It was the footnote that caught the attention of Lindeman some 30 years later. Formerly a jazz pianist in New York City, he had started his PhD in the early 1990s to continue his study of jazz. However, a particular course rekindled Lindeman’s interest in music history and theory.

His professor suggested Lindeman explore Mendelssohn’s manuscripts. He pointed out that the overwhelming majority were housed in the German State Library in Berlin, which up until that time had been difficult for Western scholars to access because of the political division of the city.

But with the end of the Cold War, political, social, and economic doors were opening across Europe. With the reunification of Germany came the reunification of Berlin’s state library and access to a massive collection of German composers’ works that were previously tucked behind the Iron Curtain.

“I got all these microfilm copies of manuscripts from Berlin,” Lindeman says, “and it wasn’t hard to get them because now they were reunified and they were eager to cooperate with the West and vice versa.”

Mendelssohn’s and Moscheles’ copies of the Concerto in E Major were among the manuscripts, and Lindeman spent several years—far beyond his doctoral research—studying the scores as well as diaries, letters, and other Mendelssohn works to discover the story of the concerto.

Mendelssohn and Moscheles

Moscheles first met Mendelssohn in 1824. Moscheles was a renowned pianist in his mid-20s and was in Berlin on a concert tour. The Mendelssohns invited Moscheles to their home to give young Felix a private lesson.

After the visit, Moscheles wrote in his diary that the boy was a “phenomenon,” that he was “already a mature artist.” Moscheles claimed that he couldn’t give Mendelssohn a lesson because the boy was the better pianist.

The two became fast friends and would find opportunities to play together again. One such chance came a few years later, when Mendelssohn made his first visit to London, where Moscheles was living. Prior to the visit, Moscheles wrote to Mendelssohn suggesting they play a concerto together—specifically the two-piano concerto that he had heard in the Mendelssohn home a few years earlier. Mendelssohn agreed, and the experience was captured in a letter to his father dated July 10, 1829:

Yesterday we had our first rehearsal. . . . I had no end of fun; . . . Moscheles plays the last movement with remarkable brilliance; he shook the runs out of his sleeves. When it was over everyone said it was such a shame that we hadn’t played any cadenzas, so I at once dug up a place in the final tutti of the first movement where the orchestra has a fermata. . . . We then tried to figure out, meanwhile making a thousand pranks, whether the last little solo . . . could be left as was, since people would no doubt applaud. . . . How long are they supposed to applaud? asked Moscheles. Ten minutes, I dare say, said I. Moscheles bargained me down to five.

Lindeman speculates the heavily marked Mendelssohn manuscript received its first round of many revisions in preparation for this first London performance. “It is not clear, but it is possible that at that time the 19-year-old Mendelssohn pulled that score from the shelf—he hadn’t looked at it for five years—and said, in effect, ‘Oh, this is no good. I was 14,’ and started revising it to try to get the work up to speed,” Lindeman says.

Five years later, in 1833, Moscheles again invited his friend to perform the concerto in London, but this time Mendelssohn declined. The composer, now more mature, had revisited the concerto and determined it was unsuitable for performance. He lamented in a letter to Moscheles that “many times a musical idea would knock but no idea ever enters,” and he abandoned the unpublished score.

However, the concerto was performed at least one more time. In 1860, 13 years after Mendelssohn’s death, Moscheles was a professor of piano at the Leipzig Conservatory of Music in Germany. During an evening of music, two of his students performed Mendelssohn’s Concerto in E Major for Two Pianos from a copy Moscheles had obtained sometime during his acquaintance with Mendelssohn. He noted the event in his diary and on the manuscript itself.

It was the last known performance of the concerto, and the two scores lay ignored on library shelves for more than a century.

The Two Manuscripts

The aha moments came slowly for Lindeman. His first step was to see both manuscripts—Mendelssohn’s and Moscheles’. He began his study with microfilm copies and eventually visited the Berlin State Library to see the originals. There, the librarians equipped him with special cotton gloves and showed him the manuscripts.

“It was definitely one of the highlights of my professional life to get to hold those Mendelssohn manuscripts in my hands,” Lindeman recalls.

Mendelssohn’s version was heavily revised and illegible in places, particularly in the first movement. Lindeman noticed the juvenile handwriting of Mendelssohn’s original score was marked up by a later, more mature Mendlessohn hand. He also saw notations in German and English, not made by Mendelssohn.

Mendelssohn’s version was heavily revised and illegible in places, particularly in the first movement. Lindeman noticed the juvenile handwriting of Mendelssohn’s original score was marked up by a later, more mature Mendlessohn hand. He also saw notations in German and English, not made by Mendelssohn.

But it was through Lindeman’s meticulous page-by-page, measure-by-measure, note-by-note comparison that he made the most startling discovery: the Moscheles copy matched the first “layer” of writing in Mendelssohn’s manuscript.

“Moscheles’ copy preserves the original version of the concerto before Mendelssohn made his revisions,” Lindeman says. Mendelssohn had shown Moscheles several compositions during Moscheles’ 1824 visit to Berlin, and in his diary, Moscheles mentions an unnamed double concerto with which he was particularly impressed. It is most likely that Moscheles asked the young composer if he could hand-copy the concerto during that first visit.

However Moscheles secured his copy, the revelation was the same: Lindeman had in his hand a clean original version and a dramatically revised version. With these scores, musicologist Lindeman was able to “peer over the shoulder” of a master to watch as Mendelssohn initially composed and then substantially revised a concerto.

“Mendelssohn is regarded as a very important figure in the development of the concerto genre—a revolutionary, almost, in his complete recasting of the formal structure of the first movement,” says Lindeman.

The two scores show the transition of a youthful genius composing in the form made popular by classical composers like Mozart and Beethoven to a mature master challenging the molds of the previous generation. Moscheles also noted the difference. In his diary after the 1860 performance, he recorded: “It was interesting to hear how the 14-year-old Mendelssohn had composed like Mozart. In the Program Book I listed it as F. Knopse.” Knopse means bud—perhaps for “budding composer.”

Lindeman was intrigued to see how the adult Mendelssohn tried to free his original work of its Mozartian form and infuse it with the Romantic notion of musical organicism. “Page after page of cross outs, paste-overs, words written into the score, many different layers of penciled and crayoned corrections suggested to me that the composer had invested a considerable—almost incredible—amount of work in the revision of this concerto. It was obvious that the work was dear to his heart.”

Yet Mendelssohn could not make the piece match his evolved concepts of a concerto and abandoned the work.

A World Premier

But the score is no longer abandoned. In 2003 the American Piano Duo and BYU’s Philharmonic Orchestra joined to make the first-ever recording of the original version of the concerto’s first movement. They also recorded the revised version, bringing both together for listeners to compare.

One must wonder if Mendelssohn, unforgiving in his self-scrutiny, would want a work he deemed unsalvageable performed on a world stage, but it cannot be denied that the world has graciously accepted it.

“The endeavor of unearthing an earlier version of a known work may strike some as purely academic,” noted The Gramophone, one of classical music’s top publications. “For anyone interested in the (not always smooth) development of this boy genius to Romantic master or the progression of the concerto form, however, this disc holds appeal beyond its musicological importance.”

The review goes on to praise the “warmth and purpose” of BYU’s orchestra and the “wisely” and “well-judged” performance of the American Piano Duo, echoing sentiments found in reviews fromInternational Piano, American Record Guide, and CD Hotlist, among others.

“Composers like Mendelssohn are so famous and the music has been researched so often that when something new comes to light, it’s something very special indeed,” says Jeffrey L. Shumway (BM ’76), a BYU music professor. He and Del Parkinson, a Boise State University professor, make up the American Piano Duo.

“It’s like finding a gold nugget when you are mowing your lawn,” adds Kory Katseanes, conductor of the BYU Philharmonic Orchestra. “It’s just not common that you find something like this. And then to have an opportunity to be involved in the publication of this for the world is really rare. I suspect it’ll be the only chance I’ll have in my lifetime.”

Lindeman attributes the widely positive response to his research to Mendelssohn’s lingering appeal: “Many musicologists work hard to get their research out there, and the general public typically isn’t interested in somebody transcribing a mass by so-and-so. But for the most part, anybody who likes 19th-century music likes Mendelssohn.”

And like Katseanes, Lindeman knows such opportunities don’t come around every day. “It’s really a chance of a lifetime.”

Lisa Ann Thomson is a freelance writer and editor living in Salt Lake City.

INFO: The CD of Mendelssohn’s Concerto for Two Pianos in E Major is available at www.tantararecords.com, where a clip of the original concerto can be heard.