The library is expanding again – this time digitally – making holdings more accessible for students and patrons around the world.

By Jeff McClellan, ’94, Editor

THE paper is brown, its edges ragged and torn. Dark brown rectangles show where someone tried to repair the paper with transparent tape. The other four pages in front of me are standard journal size and filled with loping 19th-century script. This page is half the width of the others, and the text appears more sparse. I am intrigued, however, by this lesser of the options, in part by its unusual narrow shape but mostly by the name next to the paper: William Snow.

I’ve heard of William Snow before, but I can’t recall exactly who he was. I found these five pages while looking for information about Erastus Snow, an early apostle for the Church of Jesus Christ and the most famous of my pioneer ancestors. Now I’m wondering what connection Erastus and William may have.

I decide to look at the narrow, ragged William Snow paper, and as I click on the image, the Internet window—tuned to BYU’s Harold B. Lee Library—conjures up a much-magnified view of the document. Its edges are in worse shape than was apparent in the thumbnail, but the writing is legible: “My Father Levi Snow the Son of Zerrubbabel Snow—” I feel a jolt of recognition as I read those names, and I realize I am reading the handwriting of Erastus’ brother. I click on the scroll bar and study the page, filled with names and dates. William is listed, as is Erastus, born Nov. 9, 1818, the eighth of 11 children.

To many people this tattered page is a fairly boring family history record, a precursor to family group sheets layered like geologic strata in legal-sized genealogy books. But to me this glowing image on my computer screen is a connection to my past, a representation of a fragile document written by hands that share DNA patterns with my hands.

Digital Additions

I’ve been poking around the digital collections of the Harold B. Lee Library, casually orienting myself to the available materials. Through the web of wires that connects me to the library brain, I can read family-related research in all nine issues of BYU’s Marriage and Families magazine, and I can study Church history through more than 500 master’s theses about Mormonism. I can also admire any of nearly 9,000 works from the Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

Or I can do what I have been doing: search Trails of Hope for mentions of pioneer ancestors. The collection contains diaries and letters from 49 writers, people who, like William Snow, crossed the plains going West between 1846 and 1869. The searchable collection includes images of the actual documents as well as transcriptions of their contents.

According to newly installed university librarian Randy J. Olsen, ’73, the project to digitize these pioneer records is an example of what library staff will be doing more.”We spent the decade of the ’90s planning this library addition,” he says, referring to the underground expansion completed in 1999. “As we think about what we will be engaged in in this decade, the first decade of the next century, it will be to construct another addition to the library. But this one will be entirely digital.”

This digital addition, Olsen says, will include electronic books and journals, which are growing in number, as well as BYU-created or -owned works, such as BYU journals, theses, and works of art. The Harold B. Lee Library is, in a sense, becoming a part of the global digital library that is evolving as information repositories worldwide do the same thing BYU is doing. BYU’s unique contribution to this library will be materials, like Trails of Hope, related to Church and western American history.

The prospect of a digital library—available at any hour in any time zone—excites Olsen. He sees professors in campus lecture halls accessing the collection to refer to works of art during class discussions and students at home during the summer logging on while completing Independent Study courses. As technology shapes education, Olsen envisions great contributions from the digital library.

A New Dimension

In offices and conference rooms across the BYU campus these days, professors and administrators refer regularly to “distributed learning environments”—an educational approach in which students spend less time in classrooms in favor of individual and group learning activities. For Olsen, these discussions demonstrate the need for a digital library. “A student in a distributed learning environment isn’t bounded by the hours the class is taught and the classroom the class is taught in, and they shouldn’t be bounded either by ‘When is the library open?’ and ‘Are those books and journals available?’ The library will be open, digitally, 24 hours a day. The books will be there digitally, so they’ll always be available.”

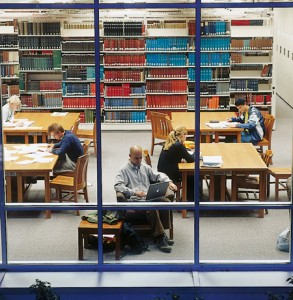

With my laptop computer, I feel like I’m participating in a “distributed working environment”—the world is my office. As I look over William Snow’s family record, I could be anywhere at anytime. But in fact, my computer is resting on a wired table on the fifth floor of the Harold B. Lee Library, a few flights of stairs down from the actual document that appears on my computer screen. Even here in this old part of the library, I can plug in to the newest part. And I am not alone.

Like cars in a grocery store parking lot, students come and go around me, digging into book bags and retrieving computers that they open up and plug in. In a distributed learning environment, a student will likely spend more time in physical places that enhance learning—places like the library, where a wealth of resources, both physical and digital, await.

The digital age is not changing the role of the library as a destination for students, it is only adding a dimension. BYU librarians report responding to Internet queries through the real-time “Ask a Librarian” feature from students sitting somewhere in the library, even though the service is available off campus as well. Library staff have noticed that their computer labs are so popular “that students will stand in line to use one of our labs even though there are empty seats in other labs across campus,” says Olsen. And a recent study confirms that use of the digital library is high.

“We hope to increase our presence as an intellectual center on campus,” he says, citing the library’s goal to take its collections to the university. “We are hosting more exhibits now and we are also hosting a number of lectures. We hope these efforts will attract scholars and students and this will become a center for discussion.”

Posters around the library show practical application of Olsen’s vision. In coming weeks, the library is sponsoring three exhibitions, a symposium, and the screening of a classic film from BYU’s film archives.

“The physical presence of this library on campus will continue to be the place where students come to gather, to study in a rich learning environment,” Olsen says.

Unlimited Access

As the Church of Jesus Christ grows, so grows the BYU community. In recent years distance-learning opportunities have increased and connections among BYU and other Church Educational System (CES) institutions have been enhanced. Accordingly, the potential audience served by the Harold B. Lee Library has expanded dramatically, and the digital library concept makes serving that audience a real possibility.

“The library will welcome not only the students of this university,” says Olsen, “it will reach out to the students at BYU—Hawaii, BYU—Idaho, and LDS Business College, and it will reach out beyond that as we take it to the membership of the Church. We have adopted as our mission statement, ‘A library for BYU, a library for the Church, a library for the world.'”

With such a broad mission, Olsen and his predecessor, Sterling J. Albrecht, ’71, who had directed the library since 1980, have worked with the other CES institutions of higher learning to build a library consortium, of which BYU’s library is now the center. In addition to sharing hard-copy books and digital materials, BYU’s librarians are available to help people at the other schools through the Ask a Librarian feature of the Web site.

“This library is much larger than the libraries at Rexburg or Laie,” says Olsen. “Through this online chat, our subject specialists here will be able to serve students and faculty on those campuses as well. It’s a way of stretching the resources here to ensure a high quality of education throughout the BYU system.”

Beyond students on the BYU campuses, Olsen sees BYU’s librarians and materials serving prospective students, Church members, BYU alumni, and anyone in the world. “In Latin America there is not a good system for distributing research results,” he says. “Together with the Ezra Taft Benson Agriculture and Food Institute, we are digitizing theses done in Latin America about agriculture. We hope that through this project Latin American students, researchers, and even farmers will become acquainted with research findings that will help them in their work.”

Making specialized information available to a broader audience is one of the gifts of technology. I could read William Snow’s handwriting from a university library in Chicago. From a train station in London, I could admire Minerva Teichert’s work. A BYU librarian could answer my question while I’m online in an apartment in São Paulo. Wherever and whenever I am connected to the Internet, the Harold B. Lee Library can augment my study.

“When BYU graduates leave campus,” says Olsen, expressing his hope for the library’s reach, “the library will follow them for the rest of their lives wherever they go. They can come across the Web to this library whenever they have research questions. It is a resource that encourages lifelong learning.”

To peruse the digital collections in the Harold B. Lee Library, visit lib.byu.edu and click on “Digital Collections” in the right-hand column.