By Jeff McClellan, ‘94, Editor

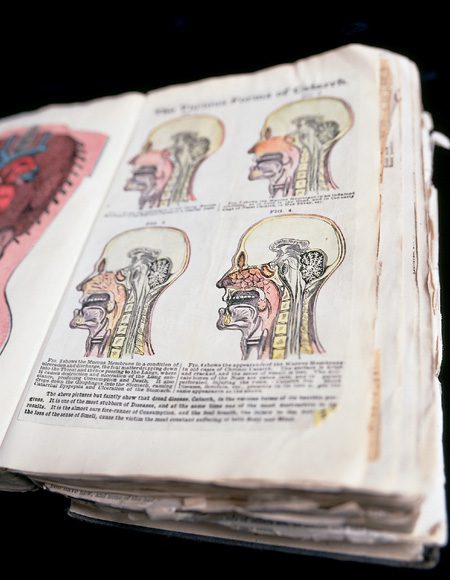

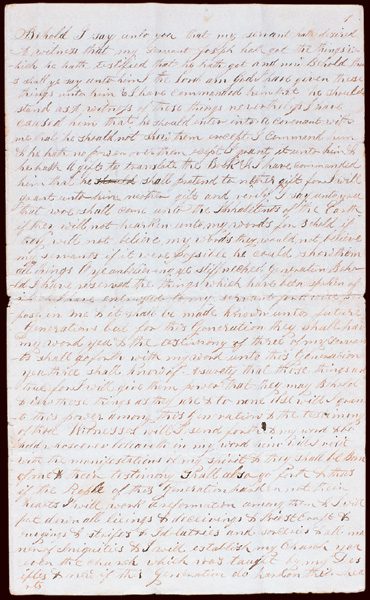

A young woman’s medical scrapbook (ca. 1880 – 1900; above) has found a home in BYU’s L. Tom Perry Special Collections

The Bible is not hard to find in BYU‘s Harold B. Lee Library. A few copies grace a prominent shelf in the sampler reading room on the main level. One floor up, the juvenile collection includes more than 30 volumes of Bible stories. And on the fifth floor, tucked away amid the ranks of white shelving units (looming like so many carefully placed dominoes), stand scores of Bibles in various languages, versions, and editions.

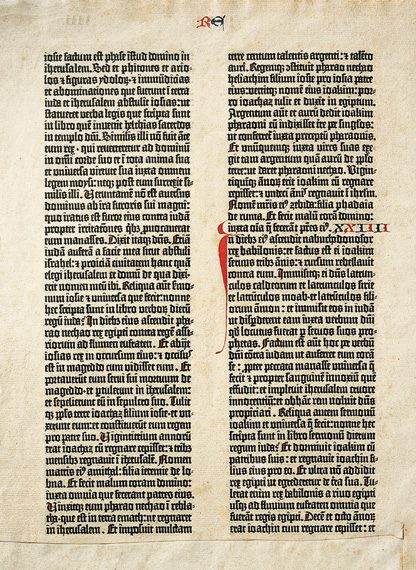

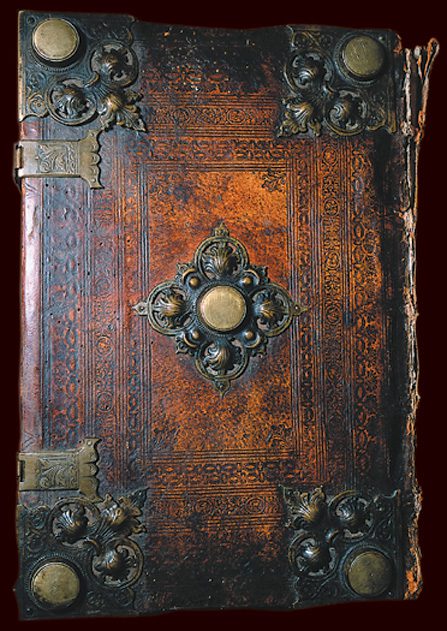

But the most fascinating Bible collection at BYU hides underground, where a 1967 Biblia Sacra illustrated by Salvador Dalí is numbered with a 1555 Biblia translated by Martin Luther. There’s also a 13th-century hand-copied Latin Vulgate Bible, a Turkish New Testament from 1905, and a page from the Bible produced by Johannes Gutenberg in about 1450.

That page is what Russell C. Taylor, ’70, is holding as he walks around a room full of two dozen students from visual arts and classics classes. It may be just one page, but as a leaf taken from the first book printed by movable type in the Western world, it is an impressive element of BYU‘s L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Special Collections boasts an extensive array of unique, unusual, and valuable works. What began in 1957 as a gathering of 1,000 books and 50 manuscript collections maintained by one curator has grown to 280,000 books, 10,000 manuscript collections, and about a million photographs managed by 14 full-time curators and processors, assisted by a band of students.

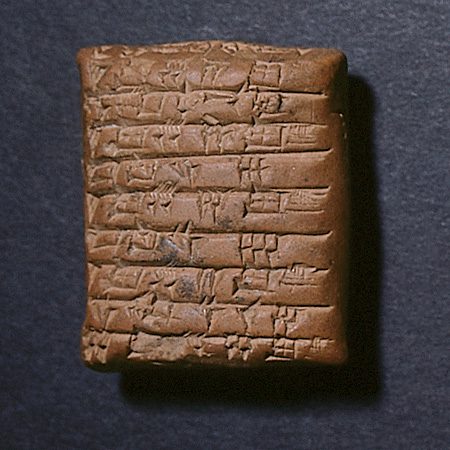

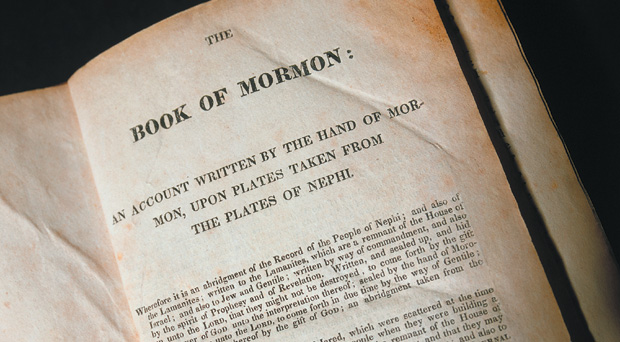

Here, on expandable shelving units in climate-controlled quarters with access-card security locks (about 33 feet below the quad), rest four 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablets, six Oscars, four first-edition copies of the Book of Mormon, 10 Ansel Adams photographs, and orders given by King Philip II of Spain in the years following the defeat of the Spanish Armada. Of course, there are a few Bibles as well.

“Special Collections is the heart of the library, and the library is the heart of the university,” says Larry W. Draper, ’78, curator of books representing Mormonism and western Americana. “So Special Collections is a pretty special place.”

PRESERVING THE PAST

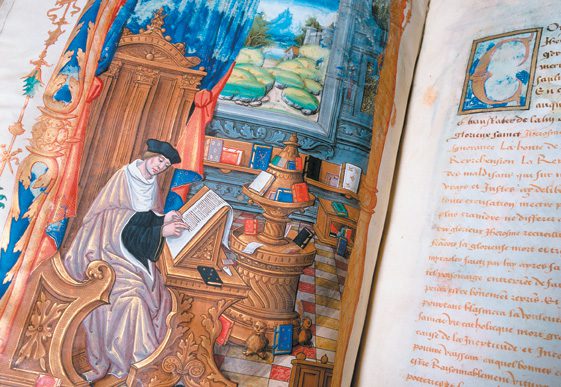

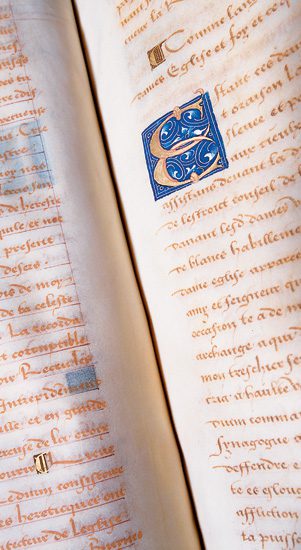

Life and Death of St. Jerome (1515) is one of the many illuminated manuscripts in Special Collections. In a place where “new acquisitions” can be half a millennium old, curators are digitizing works to make them available online. Still, says Larry Draper, “I support the use of the Internet, but not to the exclusion of holding a book that’s 500 years old and the connection with the past that that can bring.”

Each semester BYU professors bring some 50 classes to Special Collections, where curators like Taylor and Draper conduct show and tell. From one of the library’s famous wheeled carts, they produce artifacts like a copy of Doctrine and Covenants section 100 in Sidney Rigdon’s handwriting and the page from Gutenberg’s Bible.

“Gutenberg wasn’t trying to change the way books looked,” Taylor tells the students, displaying the Gutenberg page and a remarkably similar hand-copied page from the same period. “What was he trying to achieve?”

“To print more of them,” a student responds.

“OK. To make book production faster–and, hopefully, cheaper,” says Taylor, the reference curator. Gutenberg succeeded, of course, and for his accomplishment, says Taylor, Time magazine named Gutenberg one of the 10 most important people of the millennium.

Historical works like the Gutenberg Bible, the Kit Carson collection, and early records of Brigham Young Academy emphasize the purpose of Special Collections. “This is what universities are supposed to do: preserve the primary sources of our cultural heritage,” says Scott H. Duvall, ’72, chair of the Special Collections Department. “That’s why we collect these kinds of materials here.”

For Thomas R. Wells, ’80, curator of photographic archives, preserving primary sources means cleaning, cataloging, and carefully storing images that represent early photography, BYU, the American West, and Mormonism. Photographs and negatives can be particularly fragile, and Wells utilizes a giant walk-in refrigerator, designed to increase the life of photographic materials up to 1,000 years. Other objects in Special Collections require sewing frames, antique presses, organic solvents, and pH meters for the delicate process of repair and maintenance.

“The value of Special Collections is preserving the past and the present for the future,” says Wells. “These are the sources that history is written from.”

BACK INTO THE CULTURE

But preserving the past doesn’t mean hoarding history. The department’s stated purpose is not only to preserve but also to provide access–for both students and scholars. “If the material sits here, that’s an unwise use of those resources,” says James V. D’Arc, ’78, the arts and communications archivist. “Their value is not just in being preserved in perpetuity, but in being used–and used well.”

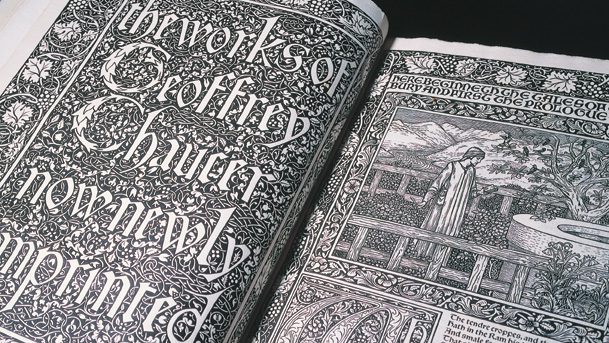

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (1896) is part of BYU’s fine printing collection. James D’Arc says the objects in Special Collections have value because the people behind them have value. “To me these aren’t dead, inert papers brought out in gray boxes for people to look at. These are things that stir the soul.”

In 1999 Special Collections patrons used about 4,000 manuscripts and 16,000 books. “If you go to any special collections repository in America and look in their reading room,” says Draper, “you’re likely to see one or two people. But you walk in here and you’re likely to see three, four, or five times that.” Draper attributes the high usage levels to the Mormon collections, which include books, newspapers, photographs, letters, and manuscripts. Second only to the collection in the Church Office Building in Salt Lake City,BYU‘s assemblage of Mormon materials is regularly accessed by undergraduate students as well as more experienced researchers.

Visiting scholars use Special Collections as well. The papers of Cecil B. DeMille–including the filmmaker’s screenplays, storyboards, and production files for The Ten Commandments–began arriving at BYU in 1977. Since then the DeMille collection has brought hundreds of scholars to Provo from all over, including one who recently visited from the Netherlands.

And through the work of visiting and local scholars, the information in Special Collections becomes more widely available. “That’s why the collections are here–to go back into the culture again,” says D’Arc.

Among BYU’s six Academy Awards (five statuettes, one certificate) is the one presented to choral arranger and composer Kenneth Darby for his work, with Alfred Newman, on The King and I (1956)

The objects in Special Collections find their way back into the culture through researchers and teachers as well as through popular media. National Geographic, for instance, has turned to BYU at least three times for historical photographs. In addition, Special Collections produces catalogs, soundtracks, and other materials to share its holdings with theBYU community and the public at large. In its exhibition gallery the department regularly displays its collections, as it did recently with Helen Foster Snow’s papers, photographs, books, and artifacts. During 10 years in China, Snow, a native Utahn, was one of the few U.S. journalists to observe firsthand the Japanese occupation and the communist revolution led by Mao Tse-tung, whom she knew personally.

“Special collections are really a culture’s memory,” says D’Arc. “By preserving these artifacts, we can continually expose them to future generations, who will see these materials in an ever-changing context.”

Such exposure, asserts David J. Whittaker, ’67, Mormon and Western manuscripts curator, is a valuable educational tool. “Something happens to a student who interacts with an original document. They become different students.”

Taylor says he enjoys the gleam in students’ eyes when they see, for example, a 600-year-old illuminated manuscript for the first time. “Something new has opened up to them,” he says.

It’s not always old things, though, that impress students. During his presentation to the visual arts and classics students, Taylor produces one of the library’s smallest books, printed less than 50 years ago. As he shows the students a two-inch-square clear plastic card, he explains that this book has been reduced some 200 times, and the almost imperceptible black spots on the plastic are individual pages–more than 1,200 of them. The book? It’s the Bible, of course.*

Sometime around 1450 Johannes Gutenberg produced this page of the Bible (left) on his printing press in Mainz, Germany, setting off a revolution in book production. In 1965 BYU president Ernest L. Wilkinson authorized a $150,000 purchase of 220 early printed books. Today that sum would only purchase one of those books. But, says Thomas Wells, “The real value is not monetary. The real value is preserving history for future scholars, genealogists, and researchers.”

A 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablet

An early-20th-century camera. “We’re custodians of things that other people have cared for in the course of hundreds, if not thousands, of years,” says curator Russell Taylor.

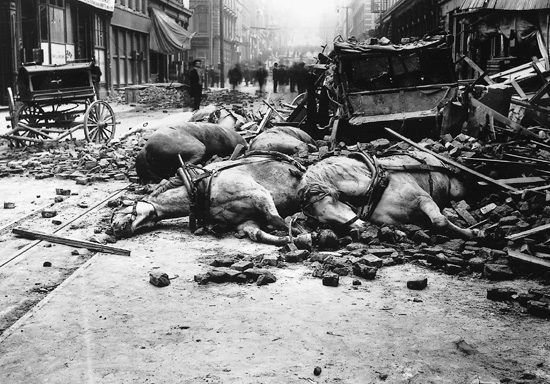

When an earthquake struck San Francisco in 1906, schoolteacher Edith Irvine documented the destruction on film (below). Her photographs adn camera (20th-century camera below) now reside at BYU. This photograph has appeared in National Geographic.

BYU’s early printed works include a Bible translated by Martin Luther and published in 1555, nine years after Luther’s death.

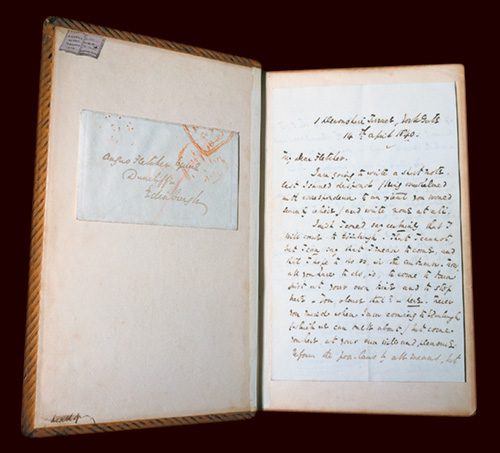

This letter from Charles Dickens to Angus Fletcher (July 1841) found its way into a copy of Dickens’ The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1837).

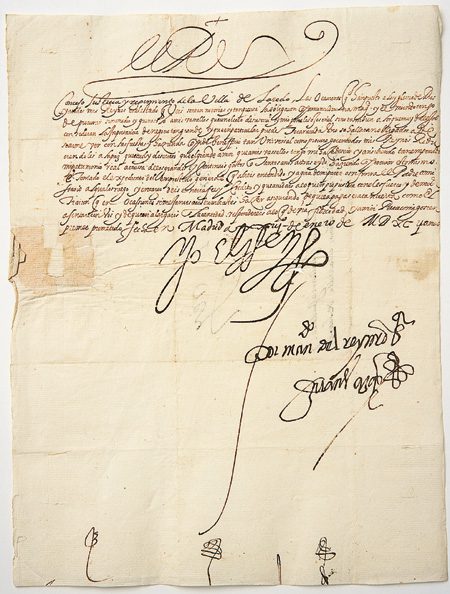

The signature of King Philip II endorses more than 150 letters (late-1591 to mid-1597) in BYU’s library. Among the letters are details of the king’s naval strategies following the defeat of the spanish Armada in 1588.

This copy of the Book of Mormon was among the 5,000 printed by E.B. Grandin in March 1830. The books, pamphlets, and newspapers in BYU’s Mormon Collection illustrate the importance of the printing press to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, says Russell Taylor. “The gospel could not have been spread around the world without it.”

Special Collections houses university archives, which include the Brigham Young Academy faculty record (1878-81) as well as photographs, publications, and personal narratives.

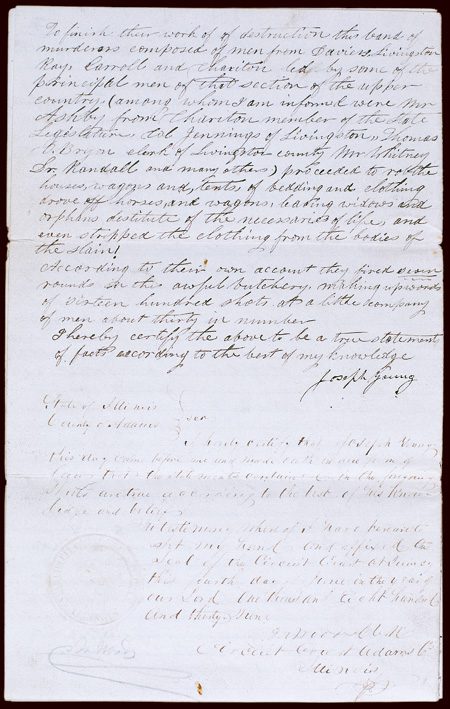

Nearly 10 years after the revelation found in D&C 5, Joseph Young recounted on paper the Haun’s Mill Massacre (October 1838).

In March 1829 Oliver Cowdery recorded a revelation received by Joseph Smith about witnesses for the Book of Mormon (D&C 5).