“It was on my watch,” says A. LeGrand “Buddy” Richards (BS ’75, PhD ’82), his laugh tinged with pain, even five years later. In December 2010 Richards, a BYU professor of educational leadership and foundations, was serving as president of the Provo South Stake, caretaker of the Provo Tabernacle.

So the 3 a.m. phone call came to him: “Smoke is coming out of the attic of the tabernacle. Thought you should know.” Richards put on warm clothes and trudged through the icy night to University and Center. “I walked up there and just—ohhh,” he remembers. “Smoke was just pouring out of both ends.” He watched as the flames burst through the roof and cast trembling shadows in the night. “When the flames were over the organ, I thought, ‘I’ve just got to go home. This is too painful.’”

The city’s old pioneer friend was lost, and the valley sat in mourning as the ruins smoldered. Over more than a century, the Provo Tabernacle had hosted stake conferences (often three on a Sunday), world-famous speakers and musicians—even a Catholic mass. Richards says what he misses most is “the mix—from the Rachmaninoffs to the road shows; the amazing speakers, the William Jennings Bryans to the sweet little gal who’s asked to get up and bear her testimony—scared to death. That’s what made it such a consecrated spot.”

As word of the fire spread, feelings of grief extended far beyond Utah Valley. Generations of BYU students—hundreds of thousands of them, now scattered around the world—had crammed into the wooden pews for a spring convocation or dashed up a spiral staircase, late for a rehearsal. They had leaned back from the balcony’s brass rail, eyes closed, as a December choir’s hallelujahs reverberated around and within. And beneath windows depicting beehives, books, and lighted torches, these students had attended to words academic and spiritual—body and mind both illuminated as tinted columns of light passed over their heads with unhurried grace, like a blessing.

Two days after the fire, President Richards stood with fire officials in the snow outside the charred eastern doorway. They were there to determine if the walls were stable enough for an investigation to begin. Peering through a window, Richards surveyed the devastation—“like something from WWII.” The balcony had crashed down. An original Minerva Teichert painting had been reduced to ashes. The $2 million organ was destroyed. But then he saw it. Sitting upright atop the rubble where the foyer had been was a framed print of The Second Coming—scorched everywhere except around the figure of the descending Savior.

“It was like it said to me, ‘Okay, Richards. You know whose house this is? If I want to remodel, what’s it to you?’”

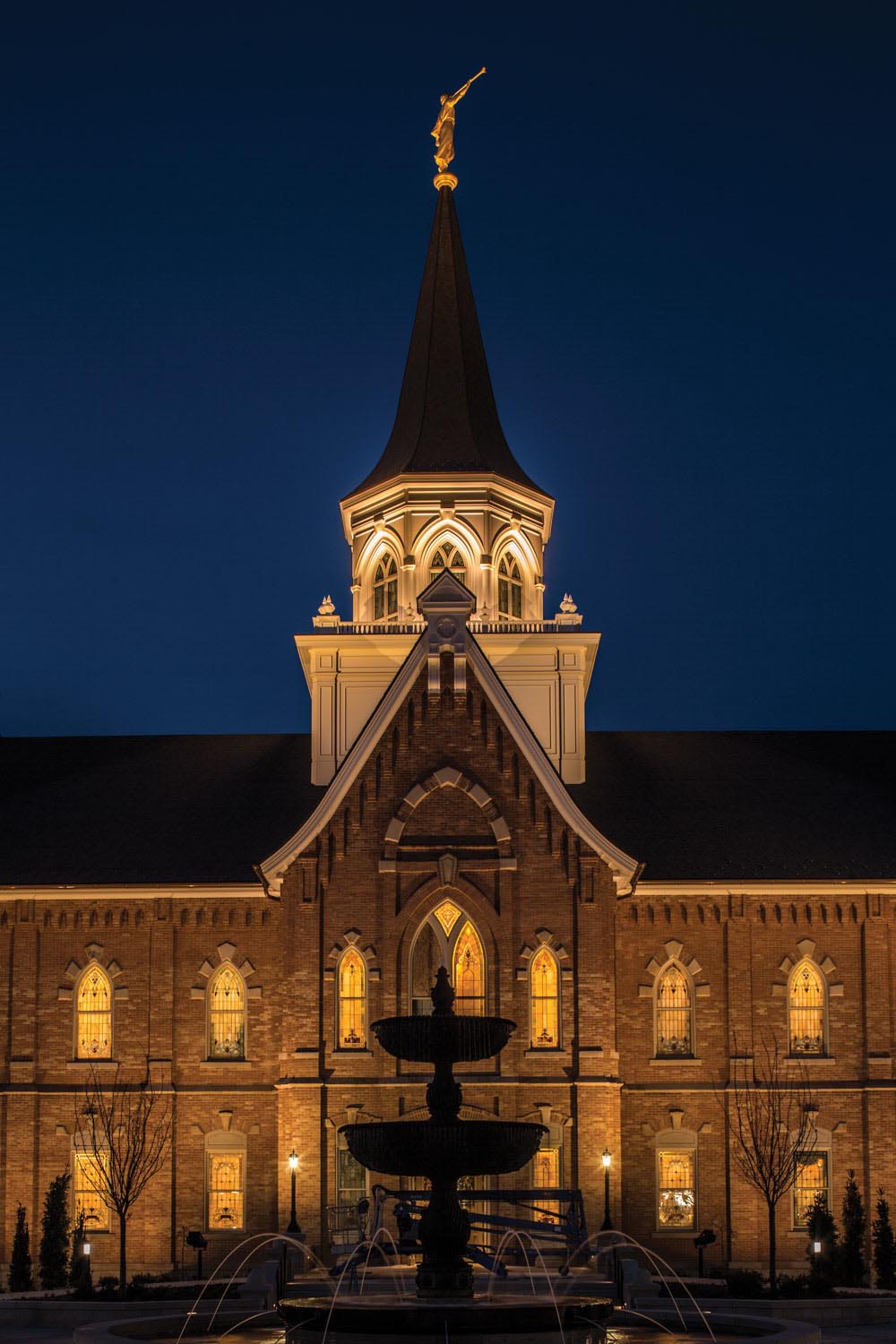

The official remodeling announcement came 10 months later, in general conference, when President Thomas S. Monson astounded the Church with plans to rebuild the structure as Provo’s second temple. Exterior brick would be scrubbed, a Moroni-topped steeple added, and stained glass replaced. The pioneer edifice would be restored, refined, and once again filled with a multi-hued flood of light.

As the temple is made ready for its March dedication, BYU Magazine here recounts the building’s long, intertwined history with Brigham Young University.

Pioneer lesson: When the prophet declares a location “the place,” take heed.

In 1849, while examining land southeast of the Fort Utah outpost, Brigham Young and his counselors made plans for a settlement with a meetinghouse at its center. But when the settlers began work on an extensive tabernacle foundation, they did it five blocks to the west of this location (at present-day Pioneer Park). The project hampered by conflict with Native Americans, the foundation was all they had to show for their efforts when Brigham Young came for a conference in 1855 and announced that this was not the place.

Six weeks later, the chastened Provo Saints broke ground once again—this time near the present-day intersection of Center Street and University Avenue—for an adobe meetinghouse, a project that would take 11 years to complete.

Although the meetinghouse was hailed as the finest in the territory, at its jam-packed dedication in 1867 Brigham Young declared it entirely inadequate for the growing population of Utah County.

For 31 years, until the dedication of a new tabernacle immediately to the south, the “Old Provo Tabernacle” was the primary house of worship and a center for community events. For a short time in 1884, after the Brigham Young Academy’s Lewis Building burned down, it even housed classes.

Although the Old Tabernacle was ultimately dismantled in 1919, echoes of its presence still reverberate in Provo. The bronze bell that had called Saints to worship was later transferred to BYU’s Education Building tower and from there eventually to the Marriott Center grounds, where students ring it to celebrate graduations and athletic victories.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

The tabernacle provided a venue for graduations and other events. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

The tabernacle provided a venue for graduations and other events. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Fifty cents per man; 25 cents per woman.

As work finally began in 1882 on the new Provo Tabernacle, Utah Stake president Abraham O. Smoot called on local members to support the project with small monthly donations. But that was hardly all that the Church asked of them. Along with their tithing, they were expected to make donations to complete the Manti and Salt Lake Temples. And then, after the Lewis Building burned down in 1884, Smoot came knocking again, hat in hand, this time representing the Brigham Young Academy Board of Trustees. What could they spare for yet another building project?

Separated by half a mile, the tabernacle and Academy Building both failed to thrive as the Church battled anti-polygamy legislation, leading to disincorporation, federal raids pursuing General Authorities, and Church-wide financial hardship.

Although the Church held its general conference in the Provo Tabernacle in 1886 and 1887, it did so in a building without permanent seating—or even a floor. And the Academy Building remained no more than a foundation until 1891.

Fundraising was Smoot’s constant refrain, himself a major donor of property and cash. And yet, when his funeral was held in 1895, it was in a still-unfinished Provo Tabernacle, and the Academy, though operational, remained deeply in debt.

After nearly two decades of labor and sacrifice, the tabernacle was finally dedicated in 1898. And the Church took over ownership of the academy and assumed its outstanding debts in 1896.

The Salt Lake Herald declared the Provo Tabernacle “one of the finest—if not the finest—house of worship in the state” and called it “a work of art.” And the Academy Building was considered the best educational facility in Utah. Born in affliction, the twin buildings became monuments to the leadership of Smoot and to the community’s devotion to the mind and spirit.

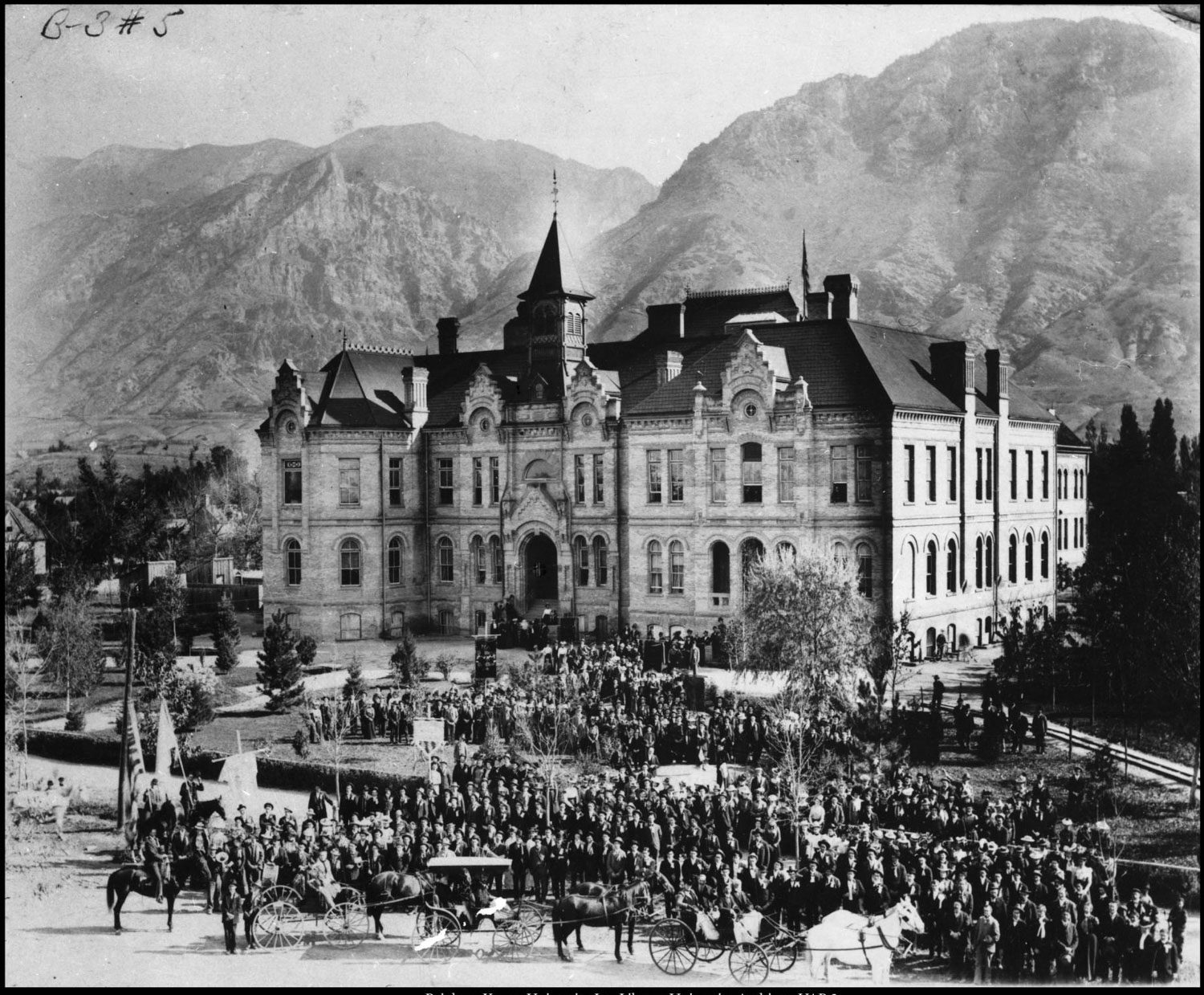

Led by Abraham O. Smoot (above, seated behind the central flag), fundraising for the tabernacle dragged on for more than 15 years. Well before its 1898 dedication, the unfinished facility was used for patriotic events, concerts, and even general conferences of the Church in 1886 and 1887. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Led by Abraham O. Smoot (above, seated behind the central flag), fundraising for the tabernacle dragged on for more than 15 years. Well before its 1898 dedication, the unfinished facility was used for patriotic events, concerts, and even general conferences of the Church in 1886 and 1887. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Deaf and blind activist Helen Keller, pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff, violinist Fritz Kreisler, organist Marcel Dupré, philosopher Will Durant, the John Philip Sousa band, poet Robert Frost—these are just a handful of the hundreds of thinkers, musicians, and groups who came to speak or perform in small-town Provo, usually at the tabernacle.

Most came at the invitation of Herald R. Clark, a professor and later dean of BYU’s College of Commerce, who moonlighted as an impresario for the university, bringing world-renowned talent to Provo for BYU’s lyceum series for more than 50 years, from 1913 to 1966. The savvy businessman would scour the New York Times for performers’ travel schedules and invite them to stop by on their way to the West Coast or pop “over the mountain” during a trip to Denver. More than 300 agreed—many returning for repeat performances (the Minneapolis Symphony came five times, pianist Jan Cherniavsky 27).

For many years the tabernacle was the only venue big enough to accommodate a large audience, and it was lauded for its acoustics. Nevertheless, the facility wasn’t without its shortcomings. In 1938 Rachmaninoff famously lifted his hands mid-performance to allow “Leaping Lena”—the Orem Inter-Urban train—and its incessantly clanging bell to pass before resuming as though nothing had happened. A decade later, when famed Broadway baritone Ezio Pinza sang his trademark “Some Enchanted Evening,” a bat began flying circles in the tabernacle, swooping at the performer’s open mouth. Dean Clark and others came to the rescue, swinging brooms and mops until the bat eventually lost energy or interest. And the show went on.

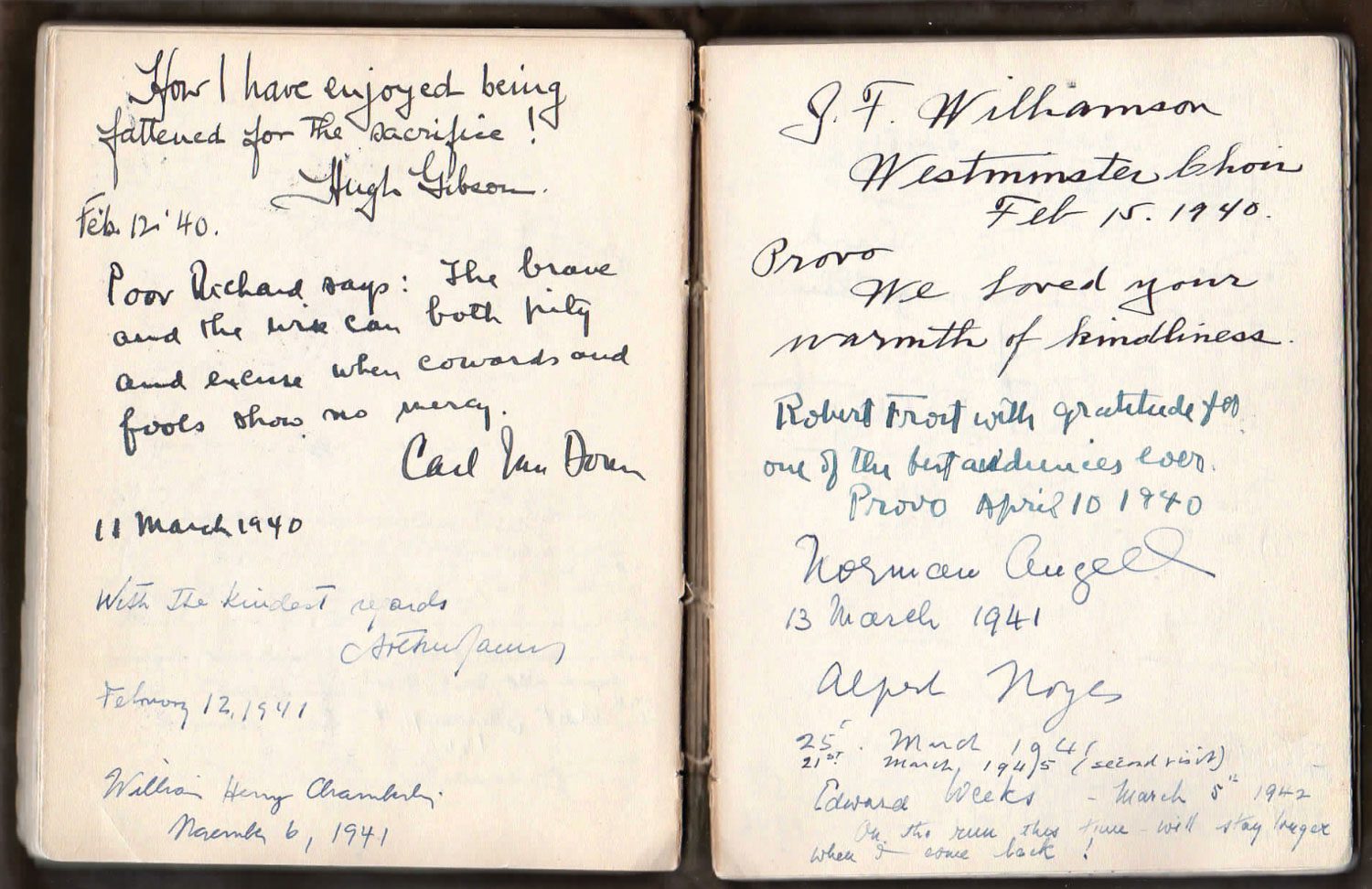

“With gratitude for one of the best audiences ever,” wrote poet Robert Frost in a BYU memory book following his April 1940 reading. The tireless efforts of BYU administrator Herald R. Clark brought more than 300 prominent poets, speakers, and musicians to the tabernacle over half of a century. Photo: courtesy Brad Clark.

“With gratitude for one of the best audiences ever,” wrote poet Robert Frost in a BYU memory book following his April 1940 reading. The tireless efforts of BYU administrator Herald R. Clark brought more than 300 prominent poets, speakers, and musicians to the tabernacle over half of a century. Photo: courtesy Brad Clark.

Utah County bands gather in front of the tabernacle following a BYU Founder’s Day Parade, circa 1910. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Utah County bands gather in front of the tabernacle following a BYU Founder’s Day Parade, circa 1910. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Built simultaneously, the Brigham Young Academy Building and Provo Tabernacle both served the educational and spiritual needs of the community. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Built simultaneously, the Brigham Young Academy Building and Provo Tabernacle both served the educational and spiritual needs of the community. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

President Heber J. Grant hands out diplomas at a 1930s BYU graduation. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

President Heber J. Grant hands out diplomas at a 1930s BYU graduation. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Long before BYU grads began marching into the Marriott Center for commencement exercises, students paraded down University Avenue in robes and mortarboards. The six-block processional began at the white gates outside the Education Building on the Academy block and ended at the Provo Tabernacle. Although graduation was moved to the new Joseph Smith Building in 1941 (and later to the Smith Fieldhouse and Marriott Center), college convocations continued to be held in the tabernacle until it burned in 2010.

BYU president Franklin S. Harris and Church President Heber J. Grant lead a 1934 procession of graduates down University Avenue to the tabernacle. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

BYU president Franklin S. Harris and Church President Heber J. Grant lead a 1934 procession of graduates down University Avenue to the tabernacle. Photo: L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

Much was lost in the fire that engulfed the Provo Tabernacle in December 2010. But with the announcement of its rebuilding as a temple, an opportunity arose for BYU to help uncover things long hidden. Beginning in January 2012 archaeology faculty and students (like Katie K. Richards [BA ’09, MA ’14], below) excavated the foundation of the original tabernacle completed in 1867 and razed in 1919. The team found dozens of items buried for nearly 100 years: coins, a fountain pen, a broach, a gold ring, a doll. Later that fall, the Church invited the archaeological team back to unearth a nearby 1875 baptistry, “hallowed ground,” according to Richard K. Talbot (BS ’79, MPA ’82, MA ’97), director of BYU’s Office of Public Archaeology. He said that such experiences help bridge the university to “a very rich history of Provo that is hard to see sometimes, but it’s there.”

Photo: © 2015 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Photo: © 2015 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Photo: Jaren Wilkey.

Photo: Jaren Wilkey.

To excavate the basement of the Provo City Center Temple, workers held up the existing walls on stilts. Photo: David Simpson.

To excavate the basement of the Provo City Center Temple, workers held up the existing walls on stilts. Photo: David Simpson.

Photo: Bradley Slade.

Photo: Bradley Slade.

Photo: Bradley Slade.

Photo: Bradley Slade.

With scrubbed bricks and replaced windows, a new steeple and an overhauled floor plan, the tabernacle will be reborn as a temple in March. Photo: Bradley Slade.

With scrubbed bricks and replaced windows, a new steeple and an overhauled floor plan, the tabernacle will be reborn as a temple in March. Photo: Bradley Slade.