Savvy parents connect with their children to build powerful family firewalls.

The digital world has long been a dangerous place for children, from cyberbullying to pornography to sexting. In recent years, the danger has increased, says associate professor of computer science Charles D. Knutson (BS ’88), and too few parents are fully grasping it. The destructive features have become not just a pernicious danger but a vortex, sucking in even the best and the brightest.

“Increasingly, technology is the air we breathe,” says Knutson, father of 10 children. “We have to acclimate our children and teach them and train them how to live in a world where that is their reality.”

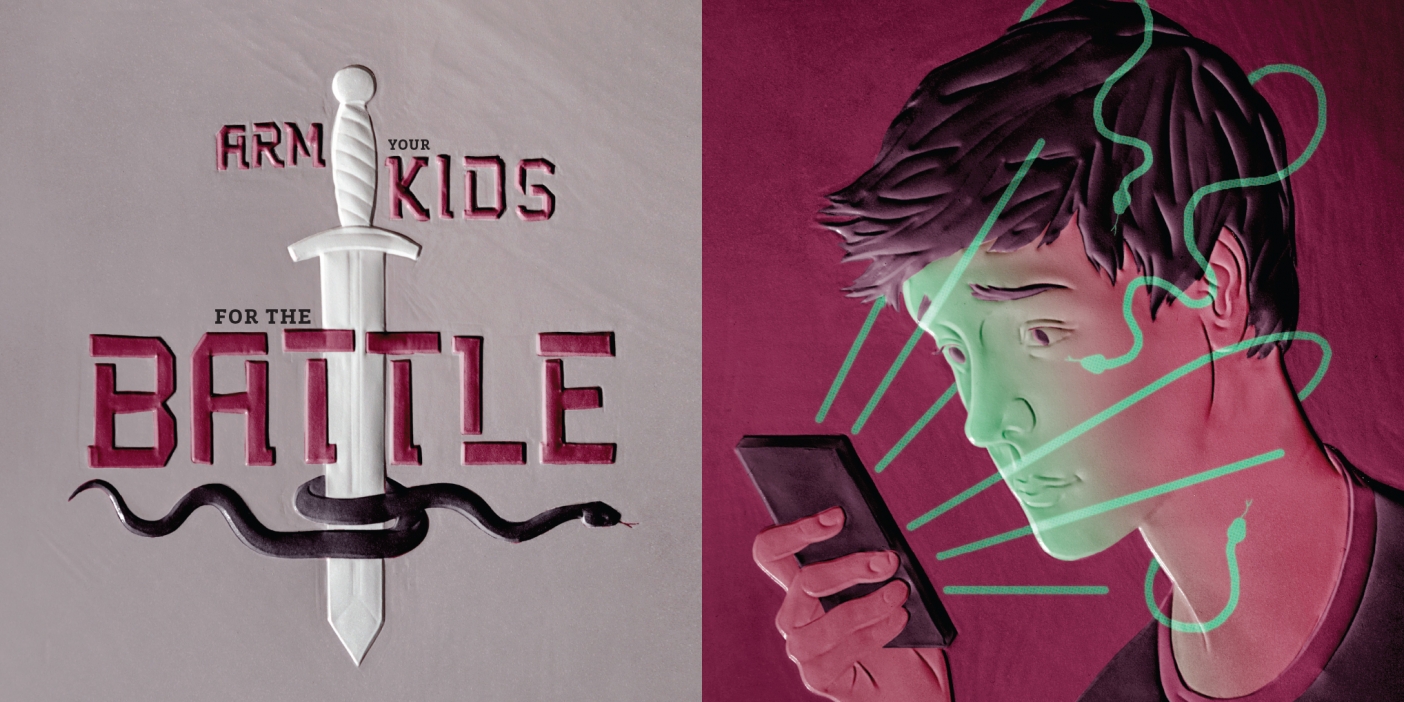

To do that, he says, first and foremost, we must be good examples. Next, parents must be frank, savvy, and loving. Most of all, he says, we need to gear up our parenting skills so that instead of fighting our children we can battle with them against a common enemy.

In his review of the battlefield, Knutson believes many parents aren’t grasping several key dynamics. Four disconnects, in particular, stand out.

One: Corrosive Content Is Not the Only Enemy

While Latter-day Saint parents understand that Internet pornography is a grave threat, many are guarding that “front door” and forgetting about the back door, side doors, and windows. One of those side doors is online role-playing games such as World of Warcraft (currently one of the most popular games, with 12 million paid subscribers). Youth can get hooked quickly and severely, many spending dozens of hours each week inside the intense world of war planning, strategy, and battle. Knutson is seeing more and more Latter-day Saint youth who are so immersed in these virtual worlds that missions don’t seem like an option. “They think they can’t be gone for two years because their ‘guild’ needs them,” he says.

Another side door is text messaging. If you have a teenage daughter, for example, and she’s off in a corner texting her friends during a family gathering, then she is emotionally withdrawing from her family. “Emotional withdrawal is a step on the road to spiritually falling asleep. You don’t have to access corrosive material to die spiritually,” says Knutson.

Helping sons and daughters avoid these addictions starts with careful parental supervision during the most vulnerable years—about ages 12 to 18. Prevention starts much sooner, of course, with teaching gospel principles and helping children identify the feelings that accompany the Spirit and the lack of the Spirit. As children get older, external controls should diminish as internal controls mature.

Two: Internet Filters and Computers in the Kitchen Are Not Enough

Responsible parents know not to put a computer in a child’s bedroom, but Knutson has found that some don’t think twice about handing their son or daughter a cell phone with a browser, messaging, and a camera. “You give your kids iPhones and they have the entire world at their fingertips. They’re taking it to bed with them, and maybe they’re accessing porn or maybe they’re just up until 4 in the morning texting their friends.” Parents who do this “have an absolute disconnect” about what they’ve done.

The solution is for parents to keep up on the latest technologies. They must investigate thoroughly and put limits on any devices they buy. That means adding filters, disabling questionable features, and controlling access. Some parents keep custody of the devices; the children check them out when it’s agreed they’re needed and check them back in at specified times, such as during homework hours or bedtime.

Three: Worry about Girls, Too

Demographically, boys tend to be more drawn to pornography, but girls are at risk as well. Approximately one-quarter to one-third of pornography consumption is by females, says Knutson.

Girls are generally more motivated socially than are boys, so they’re more vulnerable to things like the Farmville game on Facebook. Like World of Warcraft, Farmville lets users create an online persona that propels them into a compelling virtual world that can become an obsession. “I had a woman tell me once she almost threw away everything for Farmville,” he says. “That seems insane—but it all seems insane from a distance. Once you’re immersed in it, the social draw can seem irresistible.”

Girls are also more vulnerable to online relationships that can lead to real-life encounters. The most common scenario today is not a 45-year-old deceiving a 13-year-old. Rather, says Knutson, most girls who agree to meet someone they’ve met online do so knowing the man’s real age and knowing he expects sex. “Typically he’s sent her pornography and broken down her personal beliefs, her sense of right and wrong, over a period of time,” he says. Generally this happens to girls who have already emotionally separated from their families and are looking for replacement relationships.

Four: Pulling the Plug Is Not an Option

Some parents are so terrified by the prospect of their children having access to the digital world that they “pull the plug”—they forbid any and all technology in their homes. “That solution creates a false sense of security,” says Knutson. “Your children still have access to computers at the library, at school, and at their friends’ houses. And they’re going to leave home. If they go to college, now they have a laptop for the very first time, and they’ve never had to contend with what that world looks like. It’s like tossing a kid into a swimming pool who’s never seen one before.”

Pulling the plug also denies children and families the positive connectivity of the digital world, which includes Church websites, General Conference, and valuable instruction of many kinds.

The Best Protection Is Loving Communication

Knutson believes parents need to understand that their children will be exposed to corrosive material at least briefly, and often inadvertently. Once exposed, the issue becomes how children handle it. If home is a loving, trusting, informed environment, children are more likely to turn to a parent.

Suppose, for example, that a child accidentally comes across pornography and looks beyond a mere glance—maybe a lot beyond. If there’s enough emotional intimacy in the family and the child is being taught to understand the Spirit, he or she may want to talk. “If your son tells you, ‘Dad, I’ve been looking at some stuff’—then you can have a conversation about it. Now you have this amazing opportunity.”

Knutson says such a conversation could address natural feelings of attraction, the natural man versus the spiritual self, and the sanctity of sexual intimacy.

If your children know they can always talk to you, then you have unity. “Instead of operating completely alone or ashamed, your child is now operating in a context where he can get counsel, get a blessing, have an ally in the battle.”

On the other hand, if Mom or Dad’s reaction is something like, “I cannot believe this! In my home? After all we’ve taught you!”—then the child knows he’s not safe to ask for help. Without intervention, he may continue his illicit activity and become addicted.

Knutson says that when there’s emotional connection in the family, there’s a huge amount of protection. Add to that gospel teachings, and you have what amounts to a near firewall against harmful technology.

“I really believe that this is the fire this generation has to pass through,” says Knutson. “It’s the river of filthiness in Lehi’s dream. He said the iron rod was on the riverbank, so when you’re clinging to the rod, you’re very close to the river. It’s muddy, and you get splashed. But you can’t let go and move further from the filthiness. You’re where you’re supposed to be. It’s not your location that’s safe or unsafe—it’s how you behave despite your proximity to temptation. We cannot withdraw from the world but instead are called to be in it while we hold on to the scriptures, good parents, others who are godly, and, most of all, the Savior.”

Internet Safety Project

Associate professor of computer science Charles D. Knutson (BS ’88) believes parents and grandparents have a responsibility to understand “the backdrop against which your kids and grandkids are living out their probation.” For the sake of the rising generation, that means understanding technology, especially the Internet. To help, he, along with his colleagues and students, have created a website: internetsafetyproject.org. Its straightforward pages walk users simply and basically through many topics, from Facebook to identity theft and texting. The site offers podcasts, a blog, and a forum for questions and answers.