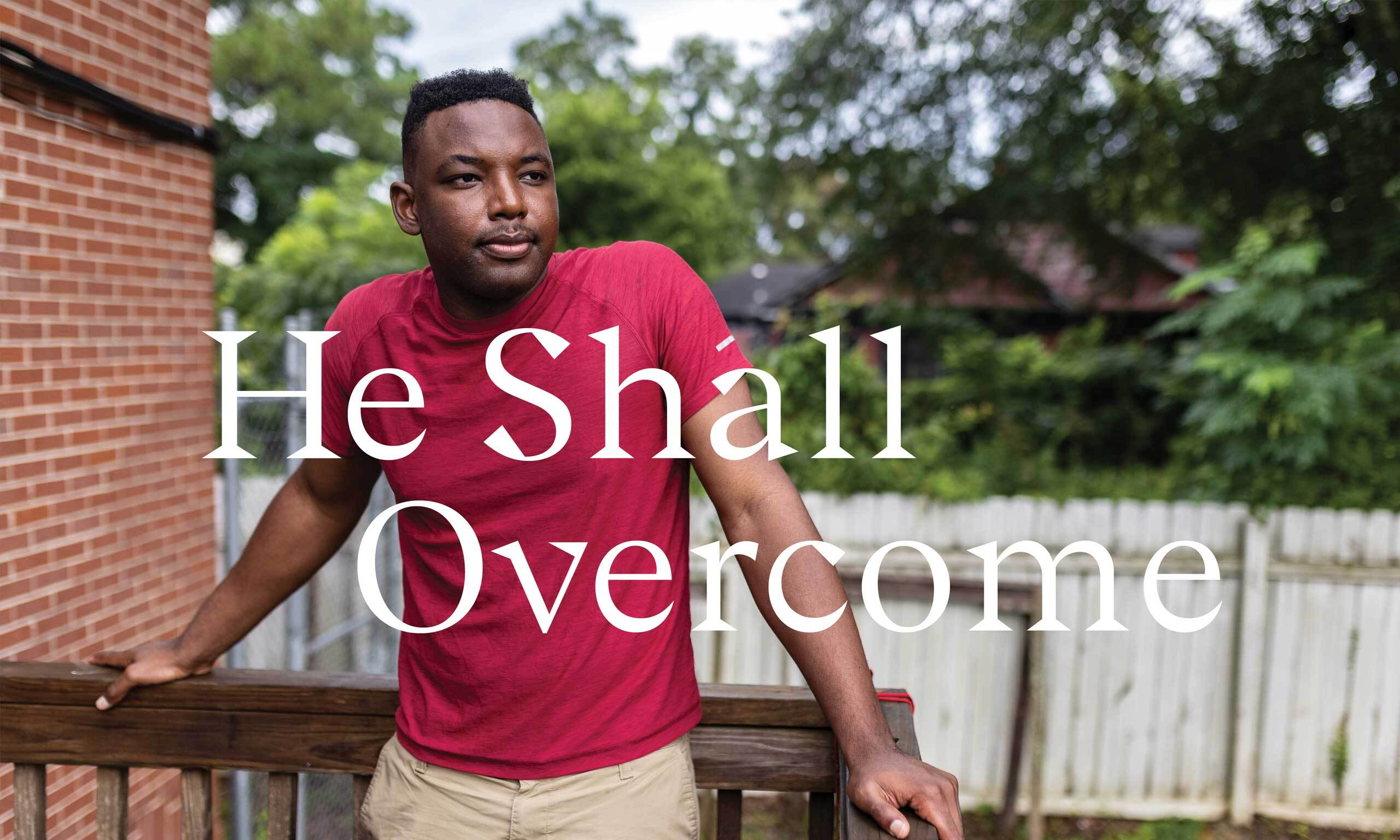

He Shall Overcome

Not homelessness, not gangs, not childhood trauma—nothing could hold back new law student Paris Thomas.

By Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07) in the Fall 2021 Issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

Gunshots—just outside the projects where he lived and played. It’s Paris D. Thomas’s (’24) earliest memory.

But intertwined with this memory is another sound: his mother’s sweet Southern voice reading Bible verses in contrast to the chaos.

“Whenever she would read to us the scriptures—stories about Elijah, David and Goliath, and Jesus—we always had peace in our home,” says Thomas.

Gang violence would take both of his brothers. “I remember [my mom] getting the call,” says Thomas, who, just 4, was too young to understand why his oldest brother, Sheldon, was gone. “But I knew I lost someone important.” At age 6 Thomas would lose his father to incarceration, and at 8, his closest brother, Jeremiah, to another shooting; Jeremiah was found in their grandmother’s backyard.

“That was the start of my political awakening, losing them,” Thomas reflects now, though he didn’t know it at the time. Today he recognizes the forces that exerted such power on his brothers, his father, and so many others in his birthplace of Atlanta and his beloved childhood home, Tuskegee, Alabama. Tuskegee is still home—a predominantly Black community where one-third of the population lives at or below the poverty line and where Thomas has spent the last few years volunteering, serving, even, at just 28, running for office. He feels a calling to do something.

That calling has now brought Thomas to BYU, where this fall he joined the Law School’s incoming class as one of the inaugural recipients of the Achievement Fellowship, given to students who have overcome significant hardship in their life (see “Fellowship of the Thrivers,” below). Law School dean D. Gordon Smith (BS ’86) says that when he heard it, Thomas’s story left him “slack-jawed.”

It’s a journey that wends through homelessness and hunger pangs to a pivotal moment: a 14-year-old high-school dropout cracking the door for two young men in white shirts and ties.

“I had no idea how that one experience would change everything,“ says Thomas.

Hunger

For most of his childhood, Thomas didn’t know disparity.

“I just thought everybody lived like that,” he says. “I never felt like I was missing out, you know?”

In his memory, he ate like a king. “Just about every home in the South is home to a chef,” he says—“the South has the best food; we know this”—and his mother, Melinda Thomas, was no exception. He describes mouthwatering ribs and his personal favorite, banana pudding. But there were other days, after losing his father and brothers, when he and his sister ate cornflakes with water or mayonnaise sandwiches. “We’d live off a bag of Cheetos for a couple days, stuff like that,” he remembers.

“[My mother] never made us feel like we weren’t blessed.” —Paris Thomas

When their situation became dire, Melinda drove her children to New Jersey, hoping to stay with family there. It didn’t pan out, and their ’80s Mitsubishi Mirage became home.

Thomas recalls one Jersey winter night in that car: “My hands were frozen. I couldn’t feel them. I couldn’t believe how cold I was.”

There’s a resilience in his voice as Thomas talks about this time, an unflappable quality. He credits his mother, who always had a wink and a smile: “She never made us feel like we weren’t blessed.”

In their time of need, says Melinda, “I put God in my life and around us.”

And they saw His blessings flow into their lives: gas money, clothes, and shoes from different churches. A diner owner who, says Thomas, “saw us kids” and hired his mom on the spot. And eventually a YMCA shelter full of fast friends.

“It was basically a gymnasium they would let you use at night with . . . rows of cots,” says Thomas. They had to be out by 7 a.m. each day, but it was there that they started getting traction. And it was there that Thomas met a shelter volunteer who secured him a scholarship to attend sixth grade at her son’s private school.

“That’s when I really first saw that there were differences,” says Thomas. “Some people actually live good,” he laughs. “It was kind of mind-blowing.”

Thomas was the only Black kid in his grade at the school. No matter, he says—no one treated him differently. And the astute young man who loved to read flourished academically. He had been exposed to a new kind of hunger.

“That kind of hunger, it teaches you . . . to stay hungry. To always strive to do and be more.”

A Door Opened

One year later the Thomases moved back to Tuskegee, near family. The same forces that influenced his brothers eventually reared again, this time for Paris.

“I remember the day someone asked me if I wanted to join [a gang],” says Thomas, who was first courted at age 12. This time the offer came with no strings attached. “They’re like, ‘You wouldn’t even have to get jumped in or go through initiation’”—the hazing process in which new members are beaten and required to commit a crime. The allure, he says, was strong: camaraderie, the ability to buy things his family never had. Many of his friends started selling drugs and joining drive-by shootings, the gang fights extending to school grounds. After walking in on his friends beating someone up in the school bathroom, Thomas made his decision—to avoid the gang, the bespectacled and studious young man dropped out of school.

“Imagine running around Tuskegee—this full Black town—with two White guys, and you’re on this pink bike with pink streamers. It’s, like, comedy gold.” —Paris Thomas

That’s when the missionaries knocked. “I tried to slam the door, but when my mom saw the badge said ‘Jesus,’ she let them in.”

The elders left a Book of Mormon. “I was reading it,” says Melinda, “but I wasn’t reading it like Paris!“ Ever the bookworm, he devoured the whole thing.

“It gave me that same peaceful feeling I had all those years ago, when my mom would read the Bible,” says Thomas. “I knew it was true because it brought those same emotions.”

He was the first in his family to be baptized, his mother and sister following soon after. And in short order, he suited up and joined forces with the elders.

“I just said, ‘Well, if you’re not going to school, you’re coming with us,’” says Chase Rigby, a brand-new missionary who drew Tuskegee as his first area. “Every single morning, after our studies, we would drive over and pick him up.”

Rigby and Thomas’s connection was “electric,” says Rigby, who had a penchant for hip-hop music and would beatbox classics and freestyle with Thomas as they walked.

Thomas was hungry to learn. “He crushed every publication in the Tuskegee ward’s materials center,” says Rigby, who remembers Thomas finishing Jesus the Christ in two weeks.

The missionaries helped Thomas find a job. They got him GED workbooks. And they taught him to ride a bike.

“I had one really bad accident,” recalls Thomas. The replacement bike they scrounged up? Pink with streamers. “Imagine running around Tuskegee—this full Black town—with two White guys, and you’re on this pink bike with pink streamers. It’s, like, comedy gold. When I saw that bike, I was like, ‘Lord, please, anything else.’ But at that point I had a strong enough testimony. I got on the bike.”

In the mornings, they all studied together—Thomas for the GED. Then they’d tract. At night they provided GED drills until Thomas had to go to work, where he delivered late-night sandwiches to Tuskegee University, turning in at 1 a.m.

When Thomas passed the GED, the elders were euphoric. “I felt like my little brother got into Stanford!” says Rigby. And then he got an idea.

Article continues below.

Fellowship of the Thrivers

Abandonment. Immigrant life. Hate crimes. Poverty. The inaugural recipients of the BYU Law School’s Achievement Fellowship “have had experiences their classmates won’t [have had],” says Law School dean of admissions Anthony M. Grover (BA ’01, JD ’04).

Born during a year of division and social unrest, the new fellowship covers all three years of tuition for students who have qualified for law school in the face of significant hardship, and it represents a conscious effort, says Dean D. Gordon Smith (BS ’86), to “welcome people of diverse backgrounds and to send a message more broadly that . . . we’re valuing these types of experiences and not just test scores.”

Thanks in part to the fellowship, the BYU Law School has admitted its most diverse class ever (22 percent minority and 51 percent female). A recent Utah Bar survey showed minority lawyers make up less than 10 percent of all Utah attorneys, while the Utah minority population is presently double that and projected to grow. By nurturing candidates from diverse backgrounds, BYU can send forth law graduates who are a better representation of “the population they serve,” says Smith.

Teaming up with the University of Utah law school dean Elizabeth Kronk Warner, Smith based the Achievement Fellowship on a similar fellowship at UCLA. With funding from six Utah law firms and one company, Domo, the program will fund up to 10 fellowships a year at each school. In addition to their scholarships, Achievement Fellows will have access to mentoring at those local firms.

Says Grover: “These Achievement Fellows have narratives that will not only help educate others here at BYU, but narratives that will arm them with empathy as they go forth to be the leaders in their communities, professions, and churches that we sorely need.”

Meet three of the inaugural Achievement Fellows, who, along with Paris Thomas, begin this fall.

Shubham D. Shah (BS ’20): Born in India and raised Hindu, Shah moved to Kenya with his family at age 4 and later to the United States. As a young man Shah was a victim of a targeted attack by a member of the Aryan Brotherhood. The perpetrator fired 12 shots at Shah and his brother, who, fortunately, were missed. “The shooting . . . taught me that life is short, to live every moment like it’s your last,” says Shah, a convert to the Church and recent BYU grad.

Jordin A. Annett (BS ’21): Growing up in rural Tennessee, Annett was abused by her father, who was jailed briefly for beating her mother. Her parents divorced, and while her mother battled depression, Annett turned to alcohol. She turned her life around and applied to BYU, graduating last spring.

“I hope to be able to use my degree to advocate for people who are unable to advocate for themselves,” says Annett, “whether that’s working in the field of international humanitarian rights or working to find justice for women and children in abusive relationships.”

Breeze K. Parker (BA ’21): Raised in a Honolulu neighborhood known for low incomes and large swaths of public housing, Parker felt her family’s economic status in Hawaii and has known the sting of prejudice. She says some people suggested she got into BYU because she was a minority—because of affirmative action. “Little do they know that I was the co-valedictorian in my major.” She plans to use her law degree in immigration work and to serve her community back home. “I hope to help with n ative issues that are hurting our community.”

Learn more about the Law School’s Achievement Fellowships.

If You Weren’t Afraid

Blake T. (’79) and Michelle Thueson Rigby’s (BA ’80) first thought upon reading their missionary son’s request: “Are you kidding? We just became empty nesters. No way.”

His pitch: this incredible kid Paris, whom he’d written so much about, needed to continue his education—could he live with them and do so in Salt Lake City? There, Thomas could attend LDS Business College (LDSBC) in an environment of believers. If he stayed in Tuskegee, the best options were an hour’s drive away, and Thomas didn’t have a license, let alone a car.

The Rigbys called the mission president—who raved about Thomas—and their hearts changed.

Elder Rigby had worked it from every angle, convincing 16-year-old Thomas and, somehow, his mother too. “I didn’t want to let him go; he was my baby,” says Melinda, “but the Spirit was talking to me. . . . I trusted he was going to have more opportunity there than I could give him.”

Thomas settled right into Rigby’s room, his clothes, and even his circle of friends, who, despite economic differences, reminded him of friends back home. “Another guy might have six or seven bedrooms in his house, but he’s just like so-and-so I know in Tuskegee,” says Thomas. “I realized people are essentially the same no matter what color, where you come from, whether you’re homeless in Tuskegee or well-to-do in Salt Lake City—we’re all the same.”

If anything, Thomas was too social, always off with friends or playing Ping Pong. “He’s a people magnet,” says Michelle. His Southern charm and inability to say no once landed him in the pickle of having three dates to the same girls-ask-guys dance. The entire community rallied around him, teaching him to drive and preparing him for his own mission—this time an official one in England.

After returning home he eventually enlisted in the navy and got his top pick of posts: Guantanamo Bay. “I’m the first person in history to [pick] that, I’m sure,” he says. An officer he admired had spoken of how the hardships of that station had refined him. “I thought, ‘I like hard things, I want to be better, and I want to be like him. I’m sold.’”

In the three years he spent in the locked-down environment of the base, Thomas the people person thrived.

“Our branch was a close-knit family, and Paris was an integral part of that,” says Soren G. Farmer (BS ’08), who served as a naval aviator and branch president there. “He makes new family everywhere he goes.” That included Filipino and Jamaican civilians who worked on the base, plus the Cuban residents at a community center for the elderly, where Thomas volunteered. “Every other week he brought a new friend to church,” says Farmer, who estimates Thomas gave 50 or more talks, testimonies, and FHE lessons, not to mention his regular lessons as Sunday School president.

Thomas completed legal clerk training on assignment there and was impressed with how the military lawyers worked so hard for the prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and for the Cuban migrants stranded there since the Cuban missile crisis. He’d had inklings to pursue law while on his mission, and here was the nudge again. “I’d always brushed it off,” he says. “Law? You come from Tuskegee. You’ve been homeless. That’s impossible.”

But one night he asked himself the question, What would you do if you weren’t afraid?

And at the end of his four-year navy service, he answered it.

What Do You See?

The next step to law school: finishing his sociology degree through the American Military University, which Thomas did remotely back in Tuskegee. There, he saw again the poverty and high unemployment, the way “people feel kind of hopeless.”

A family medical emergency “catalyzed me,” he says.

His mother, on dialysis after kidney failure, had a wrong-site needle entry. Bleeding profusely, she needed emergency transport. But Tuskegee has no ambulance, no services to speak of. “We had to call one from a city over, and it took, like, 30 minutes. All that time she was bleeding out,” he says.

“That’s when I thought, ‘Okay, I can’t sit back anymore.’”

Thomas dug into local government, attending meetings, diving deep into the challenges in his vulnerable community. Troubled by tax incentives wooing business away, the lack of published budgets, and the misappropriation of funds, he launched a campaign for county commissioner. If he won, he figured, law school could wait.

“I didn’t think he had a chance in hell,” laughs Anthony Lee, a friend of Thomas’s in Tuskegee whom Thomas calls a piece of “the living history here.” Tuskegee boasts a rich Black history as a one-time home to Rosa Parks, Booker T. Washington, and George Carver—not to mention the Tuskegee Airmen, the first all-Black squadron. Lee, for his part, was one of the first students to desegregate schools in Alabama—the namesake of the landmark Lee v. Macon County Board of Education.

“[Thomas] didn’t win,” continues Lee, “but he forced the race into a runoff,” and the incumbent ultimately lost. Thomas considered it a victory.

Lee wrote one of the recommendation letters for Thomas’s application to the BYU Law School. “I see someone young, willing, thoughtful, intelligent,” he wrote. Someone who is serving veterans, volunteering with teens in foster care. “Him with a law degree? That’s powerful. We need young people like that here. . . . Now don’t you keep him!”

Thomas doesn’t feel he’s naturally any more talented than the peers he grew up with in Tuskegee. “They had all the potential in the world,” he says. “The only difference is exposure; I was exposed to more things. I got to see there was another way, and when you can see there’s another way, I would say, most of the time, people would choose another way.”

Thomas has his own reservations, coming to BYU. “I’m feeling impostor syndrome, maybe—that I don’t have anything to contribute, that I won’t fit in, or that my approach to life will be so off-kilter . . . that I won’t see what everyone else sees.”

But to the dean of the Law School, that will be Thomas’s gift. “It’s hard to understand how laws affect the various people subject to them if those people aren’t present and able to say, ‘Hey, this is my experience, and this is how I look at this particular problem,’” says Smith. Furthermore, he adds, the research is clear: attorneys of color or from less-privileged backgrounds spend more time on access-to-justice issues, on issues that relate to the poorest members of society. “They are more interested in serving the whole.”

What does Thomas see?

“When I see a young man who’s involved in gangs, I don’t see a thug. I see [my brother] Jeremiah. When I see a homeless person, I see the people I was with every day in those shelters, slept next to. I see myself,” he says. “Our universal heritage as people is suffering, and we should try to alleviate that for each other, in whatever form that is.”

Brittany Rogers, a former editor of this publication, lives in American Fork, Utah.

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.